Friday, March 20, 2020

Notebook: The Very Thing That Happens

We've had no face-to-face contact with other people for nine days now, and in New York State, where we live (and which now has the highest coronavirus case total of any state), something like a modified lockdown is in effect. I always work at home; whether there will be work at all next week or the week after is in question. The press is still giving undue attention to the vagaries of the stock market (which mysteriously rises at times, at least fleetingly), and the man at the helm is still an idiot. We have sufficient food, sundries, and pet supplies for the time being (and more on the way), although obtaining fresh produce and fish may be a challenge in the weeks to come. In our neighborhood people with children or dogs are still walking around the block, I hear the train whistle downtown, and the temperature has climbed into the low 70s. Yesterday, in what may be our last outing for a while, I took the dog for a hike after work. Driving out of the preserve I saw two people starting out on a walk with a cat on a leash. (The things one does, to retain a bit of normal life.)

Last night we watched Call Us Ishmael, an entertaining documentary about Moby-Dick and the people who love it. I read a few of the later chapters of Fitzgerald's Odyssey. For no particular reason I pulled out Lorius, a CD by the Basque (but also part-Irish) combo named Alboka (after a kind of hornpipe) and listened to it for the first time in years. One of the livelier tracks is below. It serves, for the moment, to get the Talking Heads' "Life during Wartime" out of my head.

The title of this post is from a piece by Russell Edson, which ends, "Because of all things that might have happened this is the very thing that happens."

Labels:

Notes

Monday, March 16, 2020

Public Service Announcement

Richard Thompson, with Suzanne Vega and Loudon Wainwright.

Labels:

Music,

Richard Thompson

Friday, March 13, 2020

Notebook: State of Siege

Major disasters, natural or otherwise, have a way of forcing one not only out of one's routines but out of mental patterns as well. They can reveal a great deal about human character, or (to put it less judgmentally) about human behavior. Camus famously explored this in The Plague, which was the book I instinctively turned to when the first stirrings of the current epidemic (now officially a pandemic) were heard in China. I re-read about a third of the novel, then put it aside for something unrelated I wanted to read, but by the time I was free to get back to it its theme felt too close to home. So instead I went back to fundamentals, first re-reading The Juniper Tree, the superb volume of tales from the Brothers Grimm translated by Lore Segal (and Randall Jarrell), featuring some of Maurice Sendak's most evocative illustrations, and then to Robert Fitzgerald's translation of the Odyssey. Neither of these splendid works has much relevance to the present situation (which is, in part, the point), but if matters of life and death bring one back to essentials, then these are about as essential to me as any books I can think of.

In the meantime, I avoid public places, keep an eye on the food supply (holding up so far), and take walks in the woods, which are now (unlike the forest of folk tales) probably the safest place to be.

Labels:

Lore Segal,

Maurice Sendak,

Notes

Sunday, March 01, 2020

Enkidu

From The Epic of Gilgamesh:

All his body is matted with hair,

he bears long tresses like those of a woman:

the hair of his head grows thickly as barley,

he knows not a people, nor even a country.

Coated in hair like the god of animals,

with the gazelles he grazes on grasses,

joining the throng with the game at the water-hole,

his heart delighting with the beasts in the water.

Translated by Andrew George

Labels:

Gilgamesh

Friday, February 21, 2020

Something else

John Hay:

I think one of the greatest challenges is to watch each bounded living thing with care for its particularity, as far as we can go, to find out we can go no farther. Flower, fish or leaf, child or man — they take none of our suggestions as to rules. Each has a strong language that we never quite learn. No matter how many times I try to describe the alewife by the uses of human speech, or classify its habits, its intrinsic perfection resists me. It is something else. It goes on defying my own inquiring sense of mystery.John Hay seems to have been one of those admirable obsessives (think J. A. Baker of The Peregrine) whose fascination with one species (the alewife is a kind of herring) led him to something approaching total psychic identification with his subject. Human beings and their works appear only sporadically in his account of the alewives' annual ascent into the creeks and ponds of Cape Cod — although our dams, overfishing, and pollution in fact constitute serious threats to the species. Other predators — herons and the like — pop up a little more often, but it's the the fish themselves, as they migrate inland to spawn and then, obeying currents and rhythms largely measureless to man, return to the sea, that draw the bulk of Hay's attention. But here and there, in passages such as the one above, one senses, as well, that the book isn't entirely about alewives at all, and that his skepticism extends to, and perhaps arises out of, something rather more fundamental.

The Run

Tuesday, February 04, 2020

The Limit

Years ago, a friend from grad school and I decided to spend most of one summer rambling around rural New England on foot. Sergei had been born in what was then still the Soviet Union and was studying engineering (he later pioneered a mechanism that greatly increased the efficiency of wind turbines). I was studying environmental science but had no clear career path in mind, nor would I for some time thereafter. We both figured that it wasn't going to be long before we got sucked up into some kind of corporate or academic drudgery that would keep us occupied for years, and that this might be our last chance for anything resembling freedom. Sergei wasn't even all that interested in the outdoors, but he had an adaptable character and was equally happy spending his days walking a rural road in the Northeast Kingdom as he was watching television in his dorm room or tinkering in the engineering lab.

We were both agreed that we wanted to avoid the well-traveled trails, even if that meant going out of our way or missing some of the scenic high points. We also took care not to venture too far from civilization, since our provisions were limited to whatever we could carry on our backs. We could go a day or two on trail mix and the like if we had to, but when ever possible we would load up on bread and cheese at some local store in the towns we passed along the way. Foraging wasn't something we had any inclination or background to engage in, although we did eat our share of berries we found along the roadside.

In order to minimize the weight we had to carry we didn't bring a tent, just our sleeping bags and some sheets of plastic that we thought might keep us dry but never did. Luckily it was a dry summer and most of the time we managed to find shelter of some kind when it rained. Here and there we were offered a bed for the night by people we met along the way, but we usually declined. Somehow we managed to wander from western Connecticut up through the Berkshires, across the Green Mountains and through New Hampshire into central Maine, before circling back through eastern Massachusetts and heading home, without getting eaten by bears, bitten by rattlesnakes, or murdered by psychopaths, and we were even still speaking to each other when it was all over.

I'm a lifelong insomniac, and although my symptoms abated a bit under the daily routine of trekking ten miles or more a day, I was never like Sergei, who could plod along from sunup to sundown without ever appearing tired but then for want of a better bed could sink into an apparent coma leaning against a tree when he finally came to a stop. Sometimes I fell asleep easily enough, but after an hour or so I would wake into a miserable combination of exhaustion, anxiety, and exhilaration in which I often lingered until the first grey beginnings of dawn. I would wake in the morning sore and depressed, though I bounced back soon enough once I stretched my legs and had a bite to eat.

One evening, not long after we crossed the upper Connecticut River into New Hampshire, we left the road and went off into the forest a half-mile or so to find a sheltered place for the night, not wanting to be too obvious about it since we were presumably trespassing. We found a little clearing where the undergrowth had been nibbled down by deer and spread our sleeping bags out under the stars, which on that moonless night were as brilliant and abundant as I had ever seen them. It was comfortably warm and the only sound, once we settled down, was the chattering of flying squirrels somewhere high above us. Sergei of course was out like a light at once, and I too fell asleep before long, but I woke a while later — how much later I couldn't tell, as my watch dial wasn't luminous — and at first I couldn't remember where I was. I could hear Sergei breathing lightly a few yards away and eventually I came to my senses, but with a feeling of despair that it was probably hours until dawn and that I was too agitated to return to sleep. I got up and walked around a bit, but didn't stray too far lest I stumble over something in the dark. Had I been a smoker now would have been the time to light up, but I didn't have even that recourse.

I took a sweater out of my knapsack and pulled it on against the beginnings of a chill. I sat on a fallen tree trunk and looked up at the stars and thought about everything and nothing: about the vastness of the universe and my own insignificance in it, about my family and some young women I knew from school, about the future, about a hundred things that seemed to matter at that late hour but probably wouldn't in the light of day. I don't know how much time passed by. I felt a bit drowsy but didn't have the energy to get into my sleeping bag again and wage the struggle for sleep.

From somewhere in the dark, high above, I heard a single brief sound, just distinct enough for me to recognize the hoot of a barred owl, the sturdy night-bird of the many childhood evenings I had spent out of doors. They were common enough where I grew up and often active in the day; I had seen them dozens of times. I listened until I heard the telltale call in full: Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you? Softly, not so loud as to risk waking Sergei, I echoed the call: Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you? There was dead silence for a long time, then I thought I heard a fluttering not far off. I repeated the call and the owl responded, closer this time, maybe just ten yards away. I held my breath, then gave the call once more.

Immediately, without warning, the owl swooped down and began striking its wings fiercely against my face. I fell backwards off the trunk and as it followed me down I felt its feathertips and the pressure waves of each wingbeat. I covered my eyes with my arm, expecting at any second to feel talons tearing my face. I opened my mouth to yell to Sergei for help but my voice was paralyzed and nothing emerged. Eventually the owl's rage subsided and it flew off as invisibly as it had arrived. I felt my face and my hands for blood but there was nothing. I crawled into my sleeping bag, pulled it up around my head, and lay panting, finally weeping.

At dawn I crawled out of the sleeping bag and looked around; there wasn't a feather in sight or any other indication of the incident, and except for a bruise on my elbow where I had fallen back I could have dismissed it all as a dream — but I knew it was not. When Sergei began to stir I told him what had happened. He didn't understand at first — I had to repeat the whole story — but I think in the end he believed me.

When I try to think back on the incident in a reasoned manner the encounter still baffles me, but I think I understand now that I had somehow violated a sacred boundary. It wasn't my physical presence in the clearing that had crossed a line, or even my pretending to be an owl and calling out in the dark in a language I didn't understand. It was something else; I had transgressed, if only for a second, a margin where the domain of the human reached its terminus. The owl and I could exist in the same space, but in every other way our worlds were mutually impenetrable. I could no more understand the owl's behavior that night than it could understand the road maps we carried or the pop songs that were stuck in our heads.

Sergei and I made it safely home and finished up our studies the next spring. We still drop each other a line every now and then.

NB: The above is fiction, except for the insomnia.

Saturday, January 25, 2020

The Causes of Monsters

Ambrose Paré:

The first is the glory of God. The second, his wrath. The third, too great a quantity of semen. The fourth, too small a quantity. The fifth, imagination. The sixth, the narrowness or smallness of the womb. The seventh, the unbecoming sitting position of the mother, who, while pregnant, remains seated too long with her thighs crossed or pressed against her stomach. The eighth, by a fall or blows struck against the stomach of the mother during pregnancy. The ninth, by hereditary or accidental illnesses. The tenth, by the rotting or corruption of the semen. The eleventh, by the mingling or mixture of seed. The twelfth, by the artifice of wandering beggars. The thirteenth, by demons or devils.(Quoted by Leslie Fiedler, Freaks: Myths & Images of the Secret Self)

Labels:

Notes

Saturday, January 18, 2020

On William Bullard

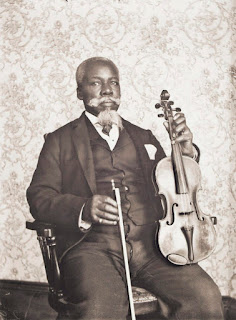

| Portrait of David T. Oswell with His Viola, about 1900 |

Countless professional and amateur portraits from the same era are floating around with little hope that the sitters will ever be identified, but Bullard used a logbook to record many of his plates and identify his subjects by name. The numbers in the logbook can be matched against numbers on the plates, and diligent digging by a team of researchers has been able to illuminate the biographies, connections, and in some cases living descendants of those pictured. In 2017, an exhibition devoted to some of these photos opened at the Worcester Art Museum under the title Rediscovering an American Community of Color. I missed out on it, but luckily a fine catalog is available under the same title.

| Portrait of Angeline Perkins and Her Children Nellie and William, 1900 |

| Portrait of Reuben Griffin Seated against a Tree, about 1901 |

| Portrait of Raymond Schuyler and his Children, Ethel, Stephen, Beatrice, and Dorothea, about 1904 |

| Portrait of Eugene Shepard, Sr., Seated in a Railcar, about 1905 |

| Portrait of Richard and Mary Elizabeth Ward Wilson, about 1902 |

For more information: Rediscovering an American Community of Color

Tuesday, January 07, 2020

Dover Beach (Matthew Arnold)

The sea is calm tonight.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

Labels:

Poetry

Monday, December 30, 2019

Mother Tongue

From The New Yorker:

Oswaldo Vidal Martín always wears the same thing to court: a striped overshirt, its wide collar and cuffs woven with geometric patterns and flowers. His pants are cherry red, with white stripes. Martín is Guatemalan and works as a court interpreter, so clerks generally assume that he is there to translate for Spanish speakers. But any Guatemalan who sees his clothing, which is called traje típico, knows that Martín is indigenous. “My Spanish is more conversational,” Martín told me. “I still have some difficulties with it.” He interprets English for migrants who speak his mother tongue, a Mayan language called Mam...Rachel Nolan, "A Translation Crisis at the Border" (January 6, 2020 issue)

Pedro Pablo Solares, a specialist in migration and a columnist for the Guatemalan newspaper Prensa Libre, travelled throughout the U.S. between 2010 and 2014, providing legal services to migrants. He found that the “immense majority” of Mayans were living in what he called ciudades espejo—mirror cities—where migrants from the same small towns in Guatemala have reconstituted communities in the U.S. “If you are a member of the Chuj community and that is your language, there are only fifty thousand people who speak that in the world. There’s only so many places you can go to find people who speak your language,” Solares told me. He described the migration patterns like flight routes: Q’anjob’al speakers from San Pedro Solomá go to Indiantown, Florida; Mam speakers from Tacaná go to Lynn, Massachusetts; Jakalteco speakers from Jacaltenango go to Jupiter, Florida.

Labels:

Languages,

Migrations

Monday, December 23, 2019

Notes for a Commonplace Book (27): Lost Powers

Charles Dickens:

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley's Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.

A Christmas Carol

Labels:

Charles Dickens,

Ghosts,

Notes

Wednesday, December 18, 2019

From the Guardian

This brings us back to impeachment. The question it poses is not whether it will be the thing that drives Donald Trump from office or whether it will be an unalloyed political boon for Democrats or other progressive forces in the country. It won’t be any of these things. Instead, the issue raised by impeachment is whether America, at this stage in its history, has what it takes to stand up against the forces of tyranny – whether there is still a passion among its people, and enough vitality in its institutions, to defend the American ideal against an unprecedented assault.Andrew Gawthorpe, "Impeachment won't force Trump out of office. But it matters for our republic." Guardian.

(Photograph: Jim Lo Scalzo/EPA)

Labels:

Politics

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

The Wolf (Paul Bowles)

Last night's Jeopardy featured, of all things, a clue that referred to Paul Bowles's venomous short story "The Frozen Fields," which is one of the few pieces Bowles set in the US and which is also, in its twisted way, a Christmas story. Of course I had to pull it out today and read it again.

The story is set at a family gathering at a rural farmhouse somewhere in the northeast, presumably in the early decades of the twentieth century, and is told largely through the eyes of Donald, a boy of six who is visiting the farm along with his parents. Despite the Norman Rockwellish ambience, all isn't well; there are whispers of illicit goings-on, and Donald's father is a surly martinet who eventually precipitates a family crisis with a rude insinuation uttered during the course of Christmas dinner.

There's no love lost between father and son (the story almost certainly draws on Bowles's difficult relationship with his own father), and when Donald lies down to sleep in the farmhouse bedroom he lets his imagination run free:

On his way through the borderlands of sleep he had a fantasy. From the mountain behind the farm, running silently over the icy crust of the snow, leaping over the rocks and bushes, came a wolf. He was running toward the farm. When he got there he would look through the windows until he found the dining room where the grown-ups were sitting around the big table. Donald shuddered when he saw his eyes in the dark through the glass. And now, calculating every movement perfectly, the wolf sprang, smashing the panes, and seized Donald's father by the throat. In an instant, before anyone could move or cry out, he was gone again with his prey still between his jaws, his head turned sideways as he dragged the limp form swiftly over the surface of the snow.So, in the end, this atypical Bowles story maybe isn't so atypical after all. It has the same sudden, pitiless violence of many of his North African tales, and the frozen fields of the rural US turn out to be just another kind of desert.

Labels:

Jeopardy,

Paul Bowles

Sunday, December 08, 2019

Notebook: December Blue

Sunday afternoon. Close enough to shake a stick at to fifty years ago, in my lonely and melancholy youth, Joni Mitchell's Blue was the one record I could never listen to enough. Shut in behind dormroom doors, I played it over and over on a clunky portable hi-fi that was already a museum piece by the time I got hold of it. There was nothing unique in this; Blue was a very popular record, at least among the people I hung out with. Mitchell sang beautifully, in spite of whatever minor technical imperfections she might have had at that point in her development, she was beautiful to look at, but most important, nothing she did before or after, not even gems like Hejira (maybe her "masterpiece," overall), and certainly nothing anyone else was doing to that point, seemed to have the same emotional directness. Sparely produced, with just Mitchell's piano, dulcimer, and guitar and a scattering of contributions from other musicians, Blue seemed to suggest that art — whatever art it was you practiced — could, if wielded with honesty and passion, not to mention genius and dedication, cut through all the pretense and posturing and give a glimpse of how we might talk — or sing — to each other if just once we could drop the masks we all carry around with us, both the ones we show to others and the ones we show to the mirror. All an illusion, perhaps, but that's not how it felt at the time.

Anyway, today I got in the car and drove a few miles to a place I like to go hiking, and I brought along a newly-purchased copy of Blue on CD for the ride. I still have my original LP, but I don't really have a functioning turntable and I'm not a big fan of streaming, so this was actually the first time I'd heard the whole thing in many years. (How did I go so long without being able to listen to "A Case of You"? It's hard to figure.) And I have to say it sounded great, probably better than ever since, whatever the merits of the CD vs. vinyl argument, my car's music system is undoubtedly better than my old hi-fi was. And the emotional impact? Yes, it's still there.

Just before our love got lost you saidBut enough of that. It was a seasonably cold but not uncomfortable December afternoon, the skies were partly cloudy, and I hiked for a couple of miles to an overlook I like to visit in the winter when the leaves don't obstruct the views of the nearby reservoir and the surrounding hills. As I neared the top I sensed movement in the sky ahead of me, and looking up I saw an enormous hawk — a red-tail, I think — settle at the top of a bare tree not far off. I switched on my camera but the angle and the light were bad, and before long the hawk leaned forward, leapt off the branch it was perched on, awkwardly bumped another nearby branch, and took flight, quickly disappearing in to the woods behind my shoulder. I finished climbing and sat on the bench that marks the summit for a while, then as I got up to leave I saw the hawk again, in flight above me, and with it a second hawk, probably its mate. The hawks wheeled above me, each in its own tight circle, in effortless command of their element, then gradually drifted further off and out of sight.

"I am as constant as a northern star"

And I said "Constantly in the darkness

Where's that at?

If you want me I'll be in the bar"

On the back of a cartoon coaster

In the blue TV screen light

I drew a map of Canada

— Oh, Canada —

With your face sketched on it twice

On the way home, having traveled several miles by now, I took a back road, and when I neared a small family cemetery adjacent to a horse farm I slowed, thinking it might be a good time and place to see something. Sure enough, as I pulled up, I saw another pair of hawks perched in a tree directly above the cemetery. I switched the camera on even before I opened the car door, but once again the angle was bad and the hawks were too wary. First one then the other took flight, making the same tight circles as the earlier pair, regarding me for a moment or two before likewise moving off.

After I got home, just at dusk, I looked out my kitchen window and saw yet another hawk perched in our peach tree — the one we haven't gotten a peach from in years because of our resident squirrels. This one we've come to think of as an old friend, as we see it in our yard almost every day, and the same or similar hawk has been visiting in the winter for years. It lingered only for a moment, then flew off.

Labels:

Joni Mitchell,

Music,

Natural history,

Notes

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

Aubade (November)

Lying awake before dawn, hearing the faint scratching of rain on the gutters, waiting for the first pale light of a winter morning to stretch across the floorboards, he feels the last traces of his dreams dissolve. A car rolls by on the wet street and he hears the damp thud of newspapers being deposited, one after another, into the driveways of the houses along the block. The sparrows have nothing to say.

Labels:

Aubade

Saturday, November 16, 2019

Pilgrimage

If I lived in Japan maybe I'd climb Mt. Fuji, but since I don't I settle for Turkey Mountain, a bump of gneiss that soars to an elevation of all of 831 feet. I like to go up a few times a year, and since the trails can be tricky once there's snow on the ground I suspect today was it for the year. It was a beautiful clear November day, warm enough that I could dispense with my coat for the brief but fairly steep climb.

From the top you can see time. The Manhattan skyline, some forty miles away, is clearly distinguishable if you look south, a nearby reservoir and the Hudson River are closer at hand to the southwest, but the surrounding woods, from this perspective, probably appear more or less as they have for hundreds, even thousands of years, and the stone beneath my feet is roughly a billion years old. It feels pretty solid and I suspect it'll be around for a while to come.

Labels:

Walking

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

A Social Call

Joseph Conrad:

Razumov had been admitted twice to that suite of several small dark rooms on the top floor: dusty window-panes, litter of all sorts of sweepings all over the place, half-full glasses of tea forgotten on every table, the two Laspara daughters prowling about enigmatically silent, sleepy-eyed, corsetless, and generally, in their want of shape and the disorder of their rumpled attire, resembling old dolls; the great but obscure Julius, his feet twisted round his three-legged stool, always ready to receive the visitors, the pen instantly dropped, the body screwed round with a striking display of the lofty brow and of the great austere beard. When he got down from his stool it was as though he had descended from the heights of Olympus. He was dwarfed by his daughters, by the furniture, by any caller of ordinary stature. But he very seldom left it, and still more rarely was seen walking in broad daylight.Edward Gorey created covers for several Anchor Press editions of Joseph Conrad's books, including Chance, Victory, and The Secret Sharer, but as far as I can tell he never did this novel, which is shown here in a design by Diana Klemin, Anchor's art director, which was issued in 1963 as part of a serious of uniform editions with introductions by Morton Dauwen Zabel. The passage above, with its jumble of forlorn objects and wraith-like women, seems tailor-made for him. Laspara and his daughters play no great role in the plot of the novel, but Conrad seems to have enjoyed describing them.

Under Western Eyes

Klemin chose two photographs corresponding to the two cities in which the novel is set. One shows the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, the other includes, at right, the tiny Île Rousseau in Geneva, where Razumov goes for a bit of privacy when he wants to do some writing.

Labels:

Joseph Conrad

Monday, November 04, 2019

The Great Circle of the Catalogue (George Gissing)

Marian Yule, the daughter and amanuensis of a London literary critic, contemplates her fate in the famous reading room of the British Museum:

Oh, to go forth and labour with one's hands, to do any poorest, commonest work of which the world had truly need! It was ignoble to sit here and support the paltry pretence of intellectual dignity. A few days ago her startled eye had caught an advertisement in the newspaper, headed ‘Literary Machine’; had it then been invented at last, some automaton to supply the place of such poor creatures as herself to turn out books and articles? Alas! the machine was only one for holding volumes conveniently, that the work of literary manufacture might be physically lightened. But surely before long some Edison would make the true automaton; the problem must be comparatively such a simple one. Only to throw in a given number of old books, and have them reduced, blended, modernised into a single one for to-day’s consumption.

The fog grew thicker; she looked up at the windows beneath the dome and saw that they were a dusky yellow. Then her eye discerned an official walking along the upper gallery, and in pursuance of her grotesque humour, her mocking misery, she likened him to a black, lost soul, doomed to wander in an eternity of vain research along endless shelves. Or again, the readers who sat here at these radiating lines of desks, what were they but hapless flies caught in a huge web, its nucleus the great circle of the Catalogue? Darker, darker. From the towering wall of volumes seemed to emanate visible motes, intensifying the obscurity; in a moment the book-lined circumference of the room would be but a featureless prison-limit.

New Grub Street

Labels:

George Gissing

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)