|

|

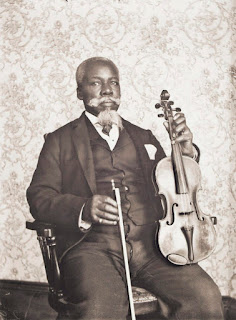

| Portrait of David T. Oswell with His Viola, about 1900 |

William S. Bullard was an amateur photographer who lived in Worcester and Brookfield, Massachsetts and captured more than 5,000 glass-plate images in the course of a twenty-year period that ended with his suicide at the age of forty-one in 1917. His negatives were carefully preserved, first by his brother and then by a postman, and over the years some of his photographs were included in illustrated volumes of local history. After the plates were acquired in 2003 by a local collector, Frank Morrill, Bullard's output gained additional significance, for Bullard, who was white, had lived in an ethnically-mixed neighborhood in Worcester, and Morrill realized that among the photographer's subjects were hundreds of individuals belonging to the city's small but vibrant African-American community.

Countless professional and amateur portraits from the same era are floating around with little hope that the sitters will ever be identified, but Bullard used a logbook to record many of his plates and identify his subjects by name. The numbers in the logbook can be matched against numbers on the plates, and diligent digging by a team of researchers has been able to illuminate the biographies, connections, and in some cases living descendants of those pictured. In 2017, an exhibition devoted to some of these photos opened at the Worcester Art Museum under the title

Rediscovering an American Community of Color. I missed out on it, but luckily a fine catalog is available under the same title.

|

| Portrait of Angeline Perkins and Her Children Nellie and William, 1900 |

Bullard had no studio and did most of his work out of doors. Forswearing hackneyed props and costumes, he shot his subjects in their own surroundings and with their own clothes and belongings (though no doubt many put on their Sunday best). He occasionally sold a few prints for modest sums, and at one point he was employed as a school photographer, but whatever ideas of making a living from his hobby he may have had (and it seems he never made much of a living from anything else either), in the end he apparently just did it all for the love of it.

|

| Portrait of Reuben Griffin Seated against a Tree, about 1901 |

|

| Portrait of Raymond Schuyler and his Children, Ethel, Stephen, Beatrice, and Dorothea, about 1904 |

We evidently don't know much about Bullard. We know the particulars of his family, his birth and death, little traces here and there, but apparently there are no accounts by people who knew him, no writings in his hand except the logbook (which includes a poem or two), and so ultimately it's hard to say what made him tick. But in a sense, we have something much better: we can see through his eyes. We know that at specific moments in his life he stood in certain spots and talked to particular people — people he no doubt knew as neighbors and quite probably as friends. We know their names, we see their expressions and what they were wearing.

|

| Portrait of Eugene Shepard, Sr., Seated in a Railcar, about 1905 |

|

| Portrait of Richard and Mary Elizabeth Ward Wilson, about 1902 |

Darryl Pinckney

once lamented, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, that "in the US, white people are able to conceive of black people who are better than they are or worse than they are, superior or inferior, but they seem to have a hard time imagining black people who are just like them." Bullard seemed to have no such difficulty. He didn't treat his subjects as minstrel-show caricatures; he treated them as they saw themselves, as people who rode bicycles, joined fraternal lodges and women's groups, went for outings in the park, and cherished their children, just like white Americans. Worcester wasn't a paradise for black people — the color bar largely denied them factory employment — but it had a living black community of individuals who embodied fundamental principles of human equality, dignity, and fallibility in an era when too many white Americans, in places like

Wilmington, North Carolina and

Tulsa, Oklahoma, seemed determined to snuff all that out.

For more information:

Rediscovering an American Community of Color

No comments:

Post a Comment