Showing posts with label Migrations. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Migrations. Show all posts

Monday, July 17, 2023

Displacement

About six weeks ago we moved out of the house where we had lived since 1990, leaving the town where we had roots stretching back much longer that, and settled, at least for now, into a one-bedroom apartment some two hundred miles away in order to be nearer to our family. Most of our stuff (including a piano and at least 90% of our books) is now in storage and more or less inaccessible. As it worked out, we left town on the very evening that an unprecedented wave of wildfire smoke moved down from Canada and into the New York metropolitan area. We actually missed the worst of it, which came the next day, but even so it made for an otherwordly five-hour drive. And the summer has continued in an ominous vein, with unprecedented heat in the Sun Belt, torrential downpours and flooding in the northeast, and further incursions of smoke.

One of our biggest worries was our cat, who is nervous and averse to being handled (except, of course, when she wants to be handled). We managed to grab her and get her into the cat carrier, then listened to her heavy breathing as we drove along. She never meowed and after a while we worried that she had simply succumbed from stress. Stopping along the way was out of the question. In fact, though initially traumatized, she came out of hiding after a day or so and now seems perfectly content. We suspect that she prefers apartment life; maybe she finds there's less to be responsible for. The dog, of course, can deal with anything as long as he's with us.

I've sought out new haunts, and found a few; more adventuresome outings will have to wait. In the meantime I'm burning through the three volumes of Simon Callow's biography of Orson Welles, borrowed from the excellent local library, and watching Chimes at Midnight.

Labels:

Migrations,

Notes

Saturday, January 15, 2022

Hermes

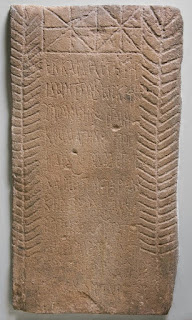

Let some traveller, on seeing Hermes of Commagene, aged sixteen years, sheltered in the tomb by fate, call out: I give you my greetings, lad, though mortal the path of life you slowly tread, for swiftly have you winged your way to the land of the Cimmerian folk. Nor will your words be false, for the lad is good, and you will do him a good service.The Hermes in this third-century Greek inscription isn't the winged messenger of the Greek gods but a teenager who died and was memorialized on what is now known as the Brough Stone, preserved in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. (Original Greek text and details here.) He had done some travelling of his own before he met his end in Roman Britain; Commagene, where he was born, was a small kingdom in what is now eastern Turkey. The Cimmerians, to whose land he flies after death, were a barbarian people known, if hazily, to the Classical world, but in the Odyssey Homer locates their country in the dark regions of the far north, just this side of Hades.

Curiously, Robert Fitzgerald doesn't use the word "Cimmerian" (the Greek is Κιμμερίων) in his translation of Book XI, line 14, but refers instead to "the realm and region of the Men of Winter." It's in Pound's Cantos, though:

Came we then to the bounds of deepest water,

To the Kimmerian lands, and peopled cities

Covered with close-webbed mist, unpierced ever

With glitter of sun-rays

Labels:

Homer,

Migrations

Tuesday, August 25, 2020

Last train out

Maybe it's the unearthly shade of red in the evening sky or the rumbling sensation below your feet, but something tells you that this time it's for real. You take inventory: what needs to come, what can be carried, what has to be battened down or left to fend for itself. Things for the road, in case...

Some people aren't budging. Take no notice, get it done. It's too late for those arguments now.

All the things you never got to: papers to organize, phone calls to make. The peonies that should have been divided years ago. Little regrets. Nothing for it.

You should have done it last year, you should have done it years ago. Maybe it's too late. No matter. Just get on with it.

In the end, one suitcase and a cloth bag with some food and a thermos. You think you must be forgetting something, but it seems to matter less with every moment that goes by. The cold feeling when you lock the door. Don't look back.

Along the road, clusters of travelers, some rushing, some hesitant. Familiar faces, no time for chat. Caught in a funnel. Momentum.

At the station, little formalities that now seem quaint. Less of a crowd than one thought. Maybe tomorrow. Maybe it's just a false alarm, after all.

As the train pulls out you don't look through the window, but the whirl around you leaves you suddenly weak at the knees. Jostle through the aisle and into a seat. A sip of cold water to settle you.

Later, passing through unfamiliar country, the grief drains away. Nothing but weariness now. What was it you forgot?

Labels:

Migrations

Friday, February 21, 2020

Something else

John Hay:

I think one of the greatest challenges is to watch each bounded living thing with care for its particularity, as far as we can go, to find out we can go no farther. Flower, fish or leaf, child or man — they take none of our suggestions as to rules. Each has a strong language that we never quite learn. No matter how many times I try to describe the alewife by the uses of human speech, or classify its habits, its intrinsic perfection resists me. It is something else. It goes on defying my own inquiring sense of mystery.John Hay seems to have been one of those admirable obsessives (think J. A. Baker of The Peregrine) whose fascination with one species (the alewife is a kind of herring) led him to something approaching total psychic identification with his subject. Human beings and their works appear only sporadically in his account of the alewives' annual ascent into the creeks and ponds of Cape Cod — although our dams, overfishing, and pollution in fact constitute serious threats to the species. Other predators — herons and the like — pop up a little more often, but it's the the fish themselves, as they migrate inland to spawn and then, obeying currents and rhythms largely measureless to man, return to the sea, that draw the bulk of Hay's attention. But here and there, in passages such as the one above, one senses, as well, that the book isn't entirely about alewives at all, and that his skepticism extends to, and perhaps arises out of, something rather more fundamental.

The Run

Monday, December 30, 2019

Mother Tongue

From The New Yorker:

Oswaldo Vidal Martín always wears the same thing to court: a striped overshirt, its wide collar and cuffs woven with geometric patterns and flowers. His pants are cherry red, with white stripes. Martín is Guatemalan and works as a court interpreter, so clerks generally assume that he is there to translate for Spanish speakers. But any Guatemalan who sees his clothing, which is called traje típico, knows that Martín is indigenous. “My Spanish is more conversational,” Martín told me. “I still have some difficulties with it.” He interprets English for migrants who speak his mother tongue, a Mayan language called Mam...Rachel Nolan, "A Translation Crisis at the Border" (January 6, 2020 issue)

Pedro Pablo Solares, a specialist in migration and a columnist for the Guatemalan newspaper Prensa Libre, travelled throughout the U.S. between 2010 and 2014, providing legal services to migrants. He found that the “immense majority” of Mayans were living in what he called ciudades espejo—mirror cities—where migrants from the same small towns in Guatemala have reconstituted communities in the U.S. “If you are a member of the Chuj community and that is your language, there are only fifty thousand people who speak that in the world. There’s only so many places you can go to find people who speak your language,” Solares told me. He described the migration patterns like flight routes: Q’anjob’al speakers from San Pedro Solomá go to Indiantown, Florida; Mam speakers from Tacaná go to Lynn, Massachusetts; Jakalteco speakers from Jacaltenango go to Jupiter, Florida.

Labels:

Languages,

Migrations

Monday, June 24, 2019

Notes from a Commonplace Book (25)

Quoted entirely out of context:

Being in a strange land and among strange men and things, meeting with customs and surrounded by circumstances widely different from all their previous experience, ignorant of the precise state of affairs here, and wanting education and flexibility by which they could adapt themselves to their new and unwonted position, they necessarily form many impracticable purposes, and endeavor to accomplish them by unfitting means. Of course disappointment frequently follows their plans. Their lives are filled with doubt, and harrowing anxiety troubles them, and they are involved in frequent mental, and probably physical, suffering.Report on Insanity and Idiocy in Massachusetts, by the Commission on Lunacy, Under Resolve of the Legislature of 1854.

Labels:

Migrations

Wednesday, May 01, 2019

Hera

Her sons are out of college and living lives of their own by the time her husband leaves. She could stay on in the house but every room has bad memories, so she winds things up and moves back to the river town where she was born. It's the same river but the people have moved on. Old acquaintances, when she happens to bump into someone she recognizes, are pleasant enough but their faces are burdened with histories she no longer shares. Downtown there are newcomers, refugees from a faraway war that has disappeared from the headlines. She rather likes the women, who are friendly, direct, and tough, but finds the men a harder read. She volunteers a bit and joins a gym, and keeps the few grey-haired men who seem to sense an opportunity at arm's length.

On overcast days she likes to walk through town and over the bridge and watch fishermen drop their lines into the dark water. Sometimes the drawbridge rises and a barge goes by, its wake slowly rippling until it breaks on the shore. She wonders what the barges carry and where they are bound, upriver empty and downriver full. Semis cross the bridge and sometimes sound their horns at her; she thinks they wouldn't bother if they could see the lines in her face.

The mail brings letters, catalogs, bills. She keeps her rooms tidy, cooks casseroles that last for days, reads into the night, rises with the dawn. Sometimes she sees great flocks high above and hears the faint cries of birds returning to Canada for the summer. She resolves to make the same trip some spring, when the moment is ripe and the last ice floes have broken up.

Labels:

Migrations

Sunday, July 01, 2018

A Point of Crisis

Former Border Control agent Francisco Cantú, writing in the New York Times:

No matter what version of hell migrants are made to pass through at the border, they will endure it to escape far more tangible threats of violence in their home countries, to reunite with family or to secure some semblance of economic stability ..."Cages Are Cruel. The Desert Is, Too." (June 30, 2018)

The logic of deterrence is not unlike that of war: It has transformed the border into a state of exception where some of the most vulnerable people on earth face death and disappearance and where children are torn from their parents to send the message You are not safe here. In this sense, the situation at the border has reached a point of crisis — not one of criminality but of disregard for human life.

We cannot return to indifference. In the aftermath of our nation's outcry against family separation, it is vital that we direct our outrage toward the violent policies that enabled it.

Further reading: Jason De León, The Land of Open Graves.

Of related interest: "The Real Story Behind a Janitor's Border Photos of Combs, Toys and Bibles" (NYT, July 2nd, 2018)

Labels:

Migrations

Thursday, August 31, 2017

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

"No Amount of Walls"

"At the extreme, if climate change wreaks havoc on the social and economic fabric of global linchpins like Mexico City, warns the writer Christian Parenti, 'no amount of walls, guns, barbed wire, armed aerial drones or permanently deployed mercenaries will be able to save one half of the planet from the other.'" — Michael Kimmelman, "Mexico City, Parched and Sinking, Faces a Water Crisis," the New York Times, February 17, 2017

Also this week, Mike Males writes, in the Los Angeles Times:

Over the last two decades, California has seen an influx of 3.5 million immigrants, mostly Latino, and an outmigration of some 2 million residents, most of them white. An estimated 2.4 million undocumented immigrants also currently live in the state...

And yet, according to data from the FBI, the California Department of Justice, and the Centers for Disease Control, the state has seen precipitous drops in every major category of crime and violence that can be reliably measured. In Trump terms, you might say that modern California is the opposite of "American carnage."...

Before the early 1990s, California had one of the country’s highest rates of violent death. It has since fallen by 18%, and did so as the average rate of violent death across the rest of the country rose 16%. Overall, Californians are 30% less likely to die a violent death today than other Americans.

In fact, compared with averages in all other states, California now has 33% fewer gun killings, 10% fewer murders overall, and 30% fewer illicit-drug deaths. When overdoses from illicit drugs rose 160% in the rest of the country, between 1999 and 2015, they rose only 27% in California.

In nearly every respect, California’s statistics contradict the image of America painted by Trump in his inaugural address — a place of rampant violence, drugs and crime, all stoked by liberal immigration policies.

Labels:

Mexico,

Migrations

Sunday, January 29, 2017

Sleepy Hollow, rising

Washington Irving's drowsy little village is now a busy multi-ethnic town, and today some 500 people from Sleepy Hollow and neighboring areas turned out on a beautiful winter afternoon for a march against the current administration's anti-immigrant policies. As the march passed street signs bearing names of immigrants dating back as far as Dutch times, the atmosphere was festive, friendly, and inclusive. The mayor joined the speakers in a park overlooking the Hudson, and there were plenty of dogs, strollers, and families.

Labels:

Community,

Migrations

Saturday, January 28, 2017

Dreamers, rising

"Succeeding for me is how I can get my revenge. I want to break the stereotype of us being here taking jobs away and not helping the economy. I want Trump to see we're the total opposite of what he thinks." — Indira Islas, quoted in Dale Russakoff's article, "The Only Way We Can Fight Back Is to Excel," from the New York Times, January 29, 2017.

Also, from The Nation: "How to Fight Trump's Racist Immigration Policies."

Labels:

Community,

Migrations

Saturday, December 17, 2016

Angels & Objects

From top: a carved figurine at the site of a former encampment of the homeless; local fauna; a relic found among the roots of a fallen tree.

The Woods, December 2016.

Labels:

Migrations,

Photography

Monday, November 21, 2016

The One Thing We Must Keep Alive

This rousing song by Los Lobos has been one of my favorites for more than thirty years. The video for it has a corny '80s feel to it now (not to mention the poor digital transfer), but it's worth a look if only for the footage of David Hidalgo and the rest of the band. In three verses and a bridge "Will the Wolf Survive?" manages to be about a lot of different things: wolves (at least as a metaphor), migrant workers and their families, cultural survival, and the truth: "something they must keep alive." (Of all of those things, wolves would now appear to be the least endangered.)

Los Lobos are still very much active, in a line-up that is unchanged except for the addition of a young and very able drummer; I saw them last night on a double-bill with the great Mavis Staples (who was in very fine form). They didn't play this song, nor did I catch any overt allusions in their music to recent political developments, but their presence itself was a reminder that there's more than one way to be American. The band switches comfortably from English to Spanish in their songs and they're perfectly capable of playing traditional norteño styles of music, but they identify as "a band from East L.A.," and they happen to be one of the great rock and blues bands of the last forty years.

Labels:

Los Lobos,

Migrations,

Music

Friday, November 11, 2016

City of Dreams

I would have preferred to write about Tyler Anbinder's superb new book about "immigrant New York" under happier circumstances, and view it as a measured celebration of the way the city has been shaped and enriched (though not without controversy) by successive waves of migrants, but as things stand it may read more like an elegy. But on second hand, I suspect not; whatever the stupidity and vindictiveness of the politics favored by our appalling president-elect and his legions, New York City will no more cease to draw migrants — legal or otherwise — than water will cease to flow downhill.

I don't want to be unfair to Anbinder and suggest that his book is a political tract. In fact, except for a few pages at the end (which strike me as well-reasoned and fair-minded), he doesn't really wade into questions of what US policy towards migrants ought to be. Instead he has done something far more important: he has written a thorough, authoritative, balanced, and readable narrative account of immigration to New York, giving some attention to the circumstances that led people to emigrate from their native countries, but far more to how they lived and how their presence made the city what it was and is, for better and (occasionally, at least) perhaps for worse. I'm sure exception will be taken to some parts of his account, especially by people with a vested interest in denying the truth about the country's past, but I think his accomplishment will stand along side books like Burrows and Wallace's Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (which it supplements and in some ways extends, since the promised sequel to the latter has not appeared).

One of Anbinder's key points is that nativism is nothing new; many of the same anti-immigrant arguments used today were trotted out against Irish Catholics, Eastern European Jews, Italian-Americans, and other now-established groups. Nor was it without its ironies: some of the most principled opponents of slavery were unrelenting anti-Catholic bigots, while immigrants made up much of the violent rabble responsible for the infamous Draft Riots of 1863. Then as now, immigration has been surrounded by controversy, exploitation, and sporadic violence.

Immigration to New York, largely unrestricted for much of the 19th century, dropped sharply in the 1920s due to developments on the national political scene; the evidence seems to suggest that the city suffered as a result of that curtailment. Today the city is vibrant and prosperous (if markedly unequal), in part as a result of new blood. What will happen in the years to come is uncertain, but I suspect that if the city staves off decline it will do so in large measure due to newcomers.

Tyler Anbinder is the author of two previous books, a fine one on New York's much-maligned Five Points neighborhood, and a study (which I plan to read) of the nativist Know Nothing Party of the 1850s.

Labels:

Migrations,

New York

Thursday, November 10, 2016

Hour of lead

From the New York Times:

[Expletive deleted] said he would quickly cancel a program Mr. Obama put in place by executive action that gave protection from deportation and work permits to about 800,000 undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children. They will lose jobs and scholarships that allowed many to attend college and start careers, and they will become vulnerable to deportation.One of the things that we're going to have to come to terms with in the near future, in addition to understandable concern about our individual and collective well-being, is the feeling of shame for being in some way collectively responsible for this kind of cruelty (proposed, we should note, by a man who, among countless other examples, openly mocks disabled people), in the sense that we all implicitly agree to abide by the same social and political compact that makes such things possible. One of the other things we're going to have to come to terms with, of course, is that millions of our fellow citizens won't be troubled by this in the least.

Image: Jasper Johns.

Title: Emily Dickinson

Resources:

Deferred Action (DACA)

New York Immigration Coalition

Labels:

Migrations,

Politics,

Soapbox

Sunday, August 02, 2015

Americans (V)

Langston

The image above is unlabelled, but knowing that its likely provenance was Oklahoma made it possible to take a guess at its location. It was printed in the real photo postcard format that was used by both commercial and amateur photographers to create mailable photographic prints, and the particular variety of Azo postcard stock on which it was printed is believed to have been manufactured between 1904 and 1918. There was only one historically black institute of higher education in the state of Oklahoma at that time, and that was the Colored Agricultural and Normal University (now Langston University) in Langston, Oklahoma. As it turns out, the guess was right; a little digging produced this photographic montage from The Oklahoma Red Book published in 1912:

Below is a closer view of the school's Mechanical Building:

Here's the same building, from the university's 1911-12 catalog:

The building in these pictures is a close fit for the one shown in the postcard, although the latter is more of a close-up and the entire smokestack is not shown. (There are no trees in the Red Book photo, which perhaps was actually taken several years earlier, before they were planted.) The identity of the young woman remains unknown, but at least we know where she was, and why she was there: she was taking advantage of one of the few opportunities for educational advancement open to African-Americans in the state of Oklahoma.

The two photos below may also possibly show Langston students, but from a later period; if so, then the family whose album this belonged to saw not just one but several members pass through Langston's doors.

The portrait photo of the male graduate is undated and unidentified, but judging by the mount it is probably later than the postcard of the young woman holding a book. The group photo is dated "Class of '33,'" and bears the inscription "From Baby to Mother Rebecca" (there is an arrow in ink over the head of the third woman from the right), which might make an identification possible (although it's not clear whether "Rebecca" was the student or the given name of "Mother Rebecca").

With these photos, or with the photo of "Laurence" from the preceding post, which might be a bit more recent, the trail grows cold. At some point, the family's careful custody of their photographic heritage came to an end. Perhaps they died out, or surviving members moved on or lost interest in their past. We don't know. Some of the photos were damaged by time and the elements or even deliberately defaced; but they survive, and even in their fragmentary fashion they carry reminders of the powerful currents of American history that formed them.

The town and university of Langston are named for John Mercer Langston, who among many other accomplishments was the first black member of the US House of Representatives from the state of Virginia. His great-nephew, the poet Langston Hughes, wrote these lines:

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,"

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Americans (III)

Sallisaw

This photograph may be the pivot of the collection. The image itself has some unusual features (which I'll note shortly), but its greatest interest may lie in the fact that it exists at all, and in how it relates to the other photos.

The photo shows two unidentified men and an unidentified woman, possibly siblings or a married couple and a brother-in-law. Someone — probably a child — has scrawled a line between the two men and a sort of spiral on the woman's mouth. The mount bears the inscription — apparently in pencil — "Wallace Sallisaw, OK." This would be the photographer L. N. Wallace, who was active in Sallisaw, Oklahoma at least by 1910 and as late as 1917, and who sometimes signed his work in that manner. (During that period he reportedly photographed an adolescent Charles Arthur Floyd, later to become notorious as Pretty Boy Floyd.) The photo above is probably no earlier than 1907, because Sallisaw was not in "Oklahoma" before then.

Wallace was a professional photographer, but I'm not clear whether this photograph was taken in a studio. What makes me wonder is the curious pose: the woman seems to be supported by the two men, and the object in the center foreground may be a bedpost; was she perhaps lying in bed, too ill to sit up? There is a seriousness and tenderness to the image that suggests this might have been the case, but maybe there's another explanation. Be that as it may, we can now start to assemble a series of pieces of evidence:

1) The family album or family collection from which all of the photographs in this series of posts were drawn came from a dealer who himself purchased it in Oklahoma.What the collection appears to document, then, is a movement after c. 1880 of some members or associates of the family network out of Tennessee and into what is now Oklahoma, and possibly into Louisiana. The evidence of this migration seems stronger in the case of Oklahoma because of the fact that there would have been relatively few African-Americans (there were some) in what was then known as Indian Territory c.1880; Louisiana, on the other hand, had long had a large African-American population. It's not impossible that the subjects of the Sallisaw photograph were descendants of African-Americans enslaved by the Cherokee, or descendants of other African-Americans who arrived in the area at an early date, but it is probably statistically more likely that they were part of the larger migration of African-Americans that took place in the 1880s and 1890s with the opening of Indian lands to settlement by non-Indians.

2) The oldest of the photos that can be assigned a location came from Franklin County or elsewhere in Tennessee and date to c.1880.

3) The latest photos that can be assigned a location (these will be examined in future posts) come from Oklahoma and Louisiana.

4) The photograph at the top of the page, which is from Sallisaw, Oklahoma, is probably later than the Tennessee images, but it is earlier than the latest Oklahoma photo or photos in the group.

So the pivotal questions are 1) can the photographs be said to document a migration of one or more family members from Tennessee or another former slave state to Oklahoma?; and 2) how would this fit in with the historical context? The answer to the first question, given the fragmentary nature of the evidence, can only be tentative. Even if the photos could be definitively assigned to a single family network, there are too many other possible narratives that could serve to fit them together. We can't prove that any of the subjects of the Tennessee photos, or any of their descendants or relations, ever migrated west; we can't make any conclusions about the connection of the subjects of the Louisiana and Missouri photos to the other subjects; and we can't prove that the Oklahoma subjects came from Tennessee. The most we can do is say that a migration from Tennessee to Oklahoma is a possible narrative connecting the evidence. But in answer to the second question, we can say that such a migration, if true, would be an emblematic narrative in line with documented migrations that took place within the time frame represented by the photos.

So the remaining questions I'll pose in this post are these: why would African-Americans have migrated in significant numbers to what was then the frontier of US settlement in the West, and did they in fact undertake such migrations? Fortunately, the answers to both of these questions are firmly historically established. Following the Compromise of 1877 and the collapse of Reconstruction, political, economic, and social conditions for African-Americans in the former slave-holding states became extremely precarious, and by the time of the Kansas Fever Exodus of 1879 a classic push-pull migration dynamic had developed to which thousands of African-Americans responded. The "push" was the reinforcement of white supremacy throughout the South, accompanied by violence and intimidation against African-Americans who sought to hold on to their rights; and the "pull" was the prospect (in some cases illusory) of independence and prosperity in newly opened lands that had no tradition of slavery. The movement of African-Americans into Kansas was soon followed by migration into Oklahoma. Over the next decades the thousands of settlers from the east would form a number of black-majority towns in Oklahoma Territory (the state of Oklahoma from 1907), and would establish the prosperous Greenwood business district of Tulsa which was later destroyed by the white riot of 1921.

Sallisaw, the seat of Sequoyah County, was not a "black town," although it may have been one of the few towns in the region to offer a photographic studio. The three subjects in the L. N. Wallace photo may have been residents, or just people passing through. Were they part of the post-Reconstruction exodus from the Southeast? We don't know; all we know is that they could have been, and that such a migration would have been common at the time.

More to come.

Further reading:

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution (New York: Harper & Row, 1988)

Nell Irwin Painter, Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas after Reconstruction (New York: Alfred A. Knopf 1977)

Sunday, July 19, 2015

Americans (I)

These photographs represent what are apparently fragments of a single African-American family album or family collection that was recently broken up and sold at auction. The photographs, which date from c. 1880 to at least 1933, offer only a few clues to the sitters' identities and histories, but if they do represent the members of a single, much-extended family (which is not quite certain), then through them we can trace a rough network of family connections and spanning at least four states and roughly fifty years of American history.

|

|

|

|

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Darryl Pinckney wrote "In the US, white people are able to conceive of black people who are better than they are or worse than they are, superior or inferior, but they seem to have a hard time imagining black people who are just like them." The most striking thing about most of the photographs presented here, and in the posts that will come, the thing that shouldn't be striking at all, is how ordinary they are. What they reflect is the bedrock of experience: ties of kinship and friendship, rites of passage, memory across generations — the very things, that is, whose existence among black people has often been denied or downplayed. In their fragmentary way, these images remind us that, whatever our histories or notions of identity may be, most of us want basically the same things and will vigorously pursue them — if the doors aren't shut in our faces.

Future posts will examine these and additional photographs from the collection in greater detail.

Saturday, August 30, 2014

The Beast (Óscar Martínez)

A few years ago when I was doing some volunteer tutoring, one of my students was a young man from Guatemala (I'll call him S., though that wasn't his initial) who already spoke and understood English fairly well, even though he was a bit embarrassed not to be able to speak the language better than he did. I don't know whether he was in the country legally (it was none of my business), but he was fortunate in having found a fairly regular full-time job that was a solid step above unskilled casual labor. I have no doubt that he was good at what he did, and it sounded like he got along well with his employer and co-workers, most of whom knew no Spanish. I worked with him for the better part of a year and in the course of the lessons we talked about a lot of things — whatever served as a way of practicing his conversational English — including his job, his life back home, what he did on the weekends, and so on.

Most of the Central American students I worked with had a good sense of humor and were fun to be around, and S. was certainly bright and likeable, but he was a little more serious than most of the others. He didn't seem depressed, like the occasional student who really seemed to be suffering serious culture shock — in fact I think he was fitting in pretty well — but it was clear that he'd been through a lot and was haunted by his experiences. He volunteered one time, without going into details, that Americans had no idea of what people like him had gone through in getting to this country, and I could tell by the look in his eyes that whatever he had personally gone through had to have been pretty bad.

Óscar Martínez is a young journalist from El Salvador who has investigated what may be the grimmest aspect of the ongoing migration crisis: not the crossing of the border itself but the nightmarish journey of Central American migrants through Mexico, an ordeal that annually subjects thousands to rape, murder, and organized kidnappings for ransom as well as to lethal falls from the northbound freight trains known as "the Beast." Unable to travel openly because of their undocumented status, these migrants are preyed upon by violent criminal syndicates who have either bought off local authorities or intimidated them into submission. At every step of the way they are fleeced or threatened; some resist and are killed, others make it through to the border only to be turned around by US authorities. Increased enforcement at the US-Mexico border has only exacerbated the situation, as newly built sections of border wall have funneled migrants into the most dangerous crossing routes, where many are extorted or forced to serve as mules for drug smugglers. Given the odds against them, the motivation that drives them must be powerful indeed. Some come for economic reasons, but as Martínez makes clear, many come simply to save their skins, having been directly threatened by local gangs or having lost family members to violence in what are currently some of the most dangerous societies on Earth: El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

The Beast (the Spanish title is Los migrantes que no importan — "the migrants who don't matter") originated as a serious of articles for the online publication El Faro. Originally published in book form in Spain in 2010, it appeared in Mexico in 2012 and has now been issued in English by Verso Books. It predates, but clearly foreshadows, the recent upsurge in migration from Central America that is being driven by ongoing violence in the region. As a work of primary first-hand journalism, it makes no attempt to propose comprehensive solutions for the migration crisis, but in providing a powerful sense of the human dimension of that crisis its value is immeasurable.

For an update, see the same author's "Why the Children Fleeing Central America Will Not Stop Coming" in the Nation, August 18/25, 2014.

Labels:

Mexico,

Migrations

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)