About a month ago, my eye was drawn to a book that has sat mostly unread on my shelf for some time, ‘The Book of Disquiet’ by Fernando Pessoa. I picked it up and randomly read a passage of such beautiful poignancy, such exquisite human precision, that the wonderment of creative expression flooded me. I told no one about it, but kept it to myself, and the impulse to write, the need to grapple with this moment has returned to me and grown from that little seed.

(From a 2020 interview with Hanif Abdurraqib)

Showing posts with label Notes. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Notes. Show all posts

Saturday, October 19, 2024

Notes for a Commonplace Book (31)

Gillian Welch:

Thursday, September 26, 2024

Notes & Queries (Zelia Nuttall)

"Paean" isn't exactly an everyday word, but it's amusing to find it being confused with an even more obscure word, one that is new to me. Merilee Grindle:

That minor error aside, Grindle's book is a fine piece of work, illuminating the colorful life and notable accomplishments of a pivotal figure in the transition between archaeology and anthropology as pursuits for wealthy amateurs and archaeology and anthropology as the domain of university-trained scholars.

Like the Chicago World's Fair, the [San Francisco] exposition of 1915 was a paeon to the technological, industrial, creative, and colonial achievements of the United States.According to Merriam-Webster, a "paeon" is "a metrical foot of four syllables with one long and three short syllables (as in classical prosody) or with one stressed and three unstressed syllables (as in English prosody)." It is sometimes confused with the far more common "paean," which is "a joyous song or hymn of praise, tribute, thanksgiving, or triumph."

In the Shadow of Quetzalcoatl: Zelia Nuttall and the Search for Mexico's Ancient Civilizations

That minor error aside, Grindle's book is a fine piece of work, illuminating the colorful life and notable accomplishments of a pivotal figure in the transition between archaeology and anthropology as pursuits for wealthy amateurs and archaeology and anthropology as the domain of university-trained scholars.

Monday, February 19, 2024

Prickly issues

The poet Donald Hall was born and raised in suburban Connecticut, but he spent many of his summers at his maternal grandparents' farm in New Hampshire in the 1930s and '40s, an experience he recollected in a memoir entitled String Too Short to Be Saved. Though he was capturing a disappearing way of life, and remembering it fondly, he largely avoided the lure of nostalgia. There are golden afternoons spent haying and tending chickens in the book, but there is also alcoholism, mental illness, and suicide among the neighbors. He would later own up to embellishing a bit; in a reprint he confessed that the abandoned railroad on Ragged Mountain that he described didn't actually exist. It was another passage in the book, though, that initially perplexed me. Hall describes a day on the farm in the company of his grandfather:

As any naturalist can tell you, there are no wild hedgehogs in New England or anywhere in the Americas, nor do they readily climb trees (pace Maurice Sendak), nor are they considered agricultural pests (though they were once popularly thought to suckle milk from cows). There are, of course, porcupines, but no one who had grown up in New England (and was later educated in part in the UK, where there are hedgehogs), would be likely to confuse the two. So what gives?

As it turns out, Hall was simply following vernacular tradition. Although "porcupine" (unlike "opossum" and "skunk") is a European word dating to the Middle Ages, few English colonists to New England would have ever seen an Old World porcupine, as the closest ones live in Italy, and faced with a spiny creature they simply borrowed the familiar name "hedgehog." The usage was common enough to have been written into law; as late as the early twentieth century the state of New Hampshire was paying bounties for killing "hedgehogs." The bounty was repealed in 1979, by which time the word had been corrected to "porcupines."

Another word for hedgehog is "urchin," from Latin ericius (see Spanish erizo, French hérisson). Today that word refers to a street waif, but its original meaning is preserved in the name for the spiny echinoderms known as "sea urchins."

Image: "Hans My Hedgehog," from The Juniper Tree.

We walked slowly uphill to the barn, which looked like a rocky ledge of Ragged in the gray light. When we were nearly to the milk shed, he suddenly pointed upward at the branches of the great maple next to the old outhouse. "Look!" he said. "There's a hedgehog!" I followed the angle of his finger and saw what resembled a bird's nest at a fork in the branches, indistinct in the late light. "Let's see how you are with a shotgun these days," he said.The animal is dispatched, not by Hall, who misses four times, but by his grandfather. In a later chapter, when the grandfather is dead, Hall returns to the farm, spots three more "hedgehogs" in the trees, and brings them down.

As any naturalist can tell you, there are no wild hedgehogs in New England or anywhere in the Americas, nor do they readily climb trees (pace Maurice Sendak), nor are they considered agricultural pests (though they were once popularly thought to suckle milk from cows). There are, of course, porcupines, but no one who had grown up in New England (and was later educated in part in the UK, where there are hedgehogs), would be likely to confuse the two. So what gives?

As it turns out, Hall was simply following vernacular tradition. Although "porcupine" (unlike "opossum" and "skunk") is a European word dating to the Middle Ages, few English colonists to New England would have ever seen an Old World porcupine, as the closest ones live in Italy, and faced with a spiny creature they simply borrowed the familiar name "hedgehog." The usage was common enough to have been written into law; as late as the early twentieth century the state of New Hampshire was paying bounties for killing "hedgehogs." The bounty was repealed in 1979, by which time the word had been corrected to "porcupines."

Another word for hedgehog is "urchin," from Latin ericius (see Spanish erizo, French hérisson). Today that word refers to a street waif, but its original meaning is preserved in the name for the spiny echinoderms known as "sea urchins."

Image: "Hans My Hedgehog," from The Juniper Tree.

Tuesday, January 02, 2024

Notes for a Commonplace Book (30)

Henry David Thoreau:

I spend a considerable portion of my time observing the habits of the wild animals, my brute neighbors. By their various movements and migrations they fetch the year about to me. Very significant are the flight of geese and the migration of suckers, etc. But when I consider that the nobler animals have been exterminated here, the cougar, panther, lynx, wolverene, wolf, bear, moose, deer, beaver, turkey, etc., etc., I cannot but feel as if I lived in a tamed and, as it were, emasculated country. Would not the motions of those larger and wilder animals have been more significant still? Is it not a maimed and imperfect nature that I am conversant with? As if I were to study a tribe of Indians that had lost all its warriors. Do not the forest and the meadow now lack expression? now that I never see nor think of the moose with a lesser forest on his head in the one, nor of the beaver in the other? When I think what were the various sounds and notes, the migrations and works, and changes of fur and plumage which ushered in the spring, and marked the other seasons of the year, I am reminded that this my life in nature, this particular round of natural phenomena which I call a year, is lamentably incomplete. I listen to a concert in which so many parts are wanting. The whole civilized country is, to some extent, turned into a city, and I am that citizen whom I pity. Many of those animal migrations and other phenomena by which the Indians marked the season are no longer to be observed. I seek acquaintance with nature to know her moods and manners. Primitive nature is the most interesting to me. I take infinite pains to know all the phenomena of the spring, for instance, thinking that I have here the entire poem, and then, to my chagrin, I learn that it is but an imperfect copy that I possess and have read, that my ancestors have torn out many of the first leaves and grandest passages, and mutilated it in many places. I should not like to think that some demigod had come before me and picked out some of the best of the stars. I wish to know an entire heaven and an entire earth.The above is a fuller version of a passage quoted in Dan Flores's sobering 2022 book Wild New World: The Epic Story of Animals & People in America. A few of the animals Thoreau mentions have since recovered (at least to an extent) in the Northeast, but by and large his lament is still valid. We live in an impoverished world. Sadder still, many of us aren't even aware of how much we've lost.

The Journal (1856)

Monday, July 17, 2023

Displacement

About six weeks ago we moved out of the house where we had lived since 1990, leaving the town where we had roots stretching back much longer that, and settled, at least for now, into a one-bedroom apartment some two hundred miles away in order to be nearer to our family. Most of our stuff (including a piano and at least 90% of our books) is now in storage and more or less inaccessible. As it worked out, we left town on the very evening that an unprecedented wave of wildfire smoke moved down from Canada and into the New York metropolitan area. We actually missed the worst of it, which came the next day, but even so it made for an otherwordly five-hour drive. And the summer has continued in an ominous vein, with unprecedented heat in the Sun Belt, torrential downpours and flooding in the northeast, and further incursions of smoke.

One of our biggest worries was our cat, who is nervous and averse to being handled (except, of course, when she wants to be handled). We managed to grab her and get her into the cat carrier, then listened to her heavy breathing as we drove along. She never meowed and after a while we worried that she had simply succumbed from stress. Stopping along the way was out of the question. In fact, though initially traumatized, she came out of hiding after a day or so and now seems perfectly content. We suspect that she prefers apartment life; maybe she finds there's less to be responsible for. The dog, of course, can deal with anything as long as he's with us.

I've sought out new haunts, and found a few; more adventuresome outings will have to wait. In the meantime I'm burning through the three volumes of Simon Callow's biography of Orson Welles, borrowed from the excellent local library, and watching Chimes at Midnight.

Saturday, January 16, 2021

Notes for a Commonplace Book (29)

Thomas De Quincey:

Of this at least, I feel assured, that there is no such thing as forgetting possible to the mind; a thousand accidents may, and will interpose a veil between our present consciousness and the secret inscriptions on the mind; accidents of the same sort will also rend away this veil; but alike, whether veiled or unveiled, the inscription remains for ever; just as the stars seem to withdraw before the common light of day, whereas, in fact, we all know that it is the light which is drawn over them as a veil -- and that they are waiting to be revealed, when the obscuring daylight shall have withdrawn.I suspect that Borges, who knew De Quincey's work well and regarded it highly, likely had this passage in the back of his mind when he wrote his famous short story about a man who suffers a head injury and becomes literally unable to forget anything.

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

That no memory is ever entirely erased is not, perhaps, an entirely untestable proposition. One could easily imagine experiments that would demonstrate the existence of "inscriptions" of which the mind has no conscious memory. But in the end it probably should be regarded as a supposition that is both certainly true — in some sense — and at the same time utterly unfathomable to rational inquiry. And it makes me think of gravity, which, if the little I understand of it is correct, never loses a faint pull on an object no matter how distant it travels.

Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Notes for a Commonplace Book (28)

Charles Dickens:

I had no thought that night — none, I am quite sure — of what was soon to happen to me. But I have always remembered since that when we had stopped at the garden-gate to look up at the sky, and when we went upon our way, I had for a moment an undefinable impression of myself as being something different from what I then was. I know it was then and there that I had it. I have ever since connected the feeling with that spot and time and with everything associated with that spot and time, to the distant voices in the town, the barking of a dog, and the sound of wheels coming down the miry hill.

Bleak House

Wednesday, April 08, 2020

Social distancing tip

Herodotus:

The Carthaginians also tell us that they trade with a race of men who live in a part of Libya beyond the Pillars of Hercules. On reaching this country, they unload their goods, arrange them tidily along the beach, and then, returning to their boats, raise a smoke. Seeing the smoke, the natives come down to the beach, place on the ground a certain quantity of gold in exchange for the goods, and go off again to a distance. The Carthaginians then come ashore and take a look at the gold; and if they think it represents a fair price for their wares, they collect it and go away; if, on the other hand, it seems too little, they go back aboard and wait, and the natives come and add to the gold until they are satisfied. There is perfect honesty on both sides; the Carthaginians never touch the gold until it equals in value what they have offered for sale, and the natives never touch the goods until the gold has been taken away.

The Histories

Labels:

Notes

Saturday, March 28, 2020

Notebook: The Line

Herman Melville:

All men live enveloped in whale-lines. All are born with halters round their necks; but it is only when caught in the swift, sudden turn of death, that mortals realize the silent, subtle, ever-present perils of life. And if you be a philosopher, though seated in the whale-boat, you would not at heart feel one whit more of terror, than though seated before your evening fire with a poker, and not a harpoon, by your side.

Moby-Dick

Sunday, March 22, 2020

Notebook: Sunday

There's a strange calm today, with some cloud cover but no wind, and the street outside has been largely quiet all day. We're keeping to the house and the back yard of our 50-foot lot. When I took the dog out I heard a lone airplane passing overhead, one of the few signs that civilization, though wounded, still exists.

Yesterday afternoon, when it was warmer, I went outside to do a bit of garden clean-up and prepare a bed for a handful of peas I'll plant in a week or so. I found a garter snake sunning itself in a patch of thyme, unconcerned with our troubles. It remained frozen while I circled around it, closer and closer, finally kneeling down a couple of feet away to get close-ups. I went back to my chores but kept an eye on it. Eventually it slithered off a bit and coiled up in some leaves, not quite invisible.

This may be our ambit for a while. We received a food delivery today, enough to tide us over for the next few weeks, barring the unforeseen.

Labels:

Notes

Friday, March 20, 2020

Notebook: The Very Thing That Happens

We've had no face-to-face contact with other people for nine days now, and in New York State, where we live (and which now has the highest coronavirus case total of any state), something like a modified lockdown is in effect. I always work at home; whether there will be work at all next week or the week after is in question. The press is still giving undue attention to the vagaries of the stock market (which mysteriously rises at times, at least fleetingly), and the man at the helm is still an idiot. We have sufficient food, sundries, and pet supplies for the time being (and more on the way), although obtaining fresh produce and fish may be a challenge in the weeks to come. In our neighborhood people with children or dogs are still walking around the block, I hear the train whistle downtown, and the temperature has climbed into the low 70s. Yesterday, in what may be our last outing for a while, I took the dog for a hike after work. Driving out of the preserve I saw two people starting out on a walk with a cat on a leash. (The things one does, to retain a bit of normal life.)

Last night we watched Call Us Ishmael, an entertaining documentary about Moby-Dick and the people who love it. I read a few of the later chapters of Fitzgerald's Odyssey. For no particular reason I pulled out Lorius, a CD by the Basque (but also part-Irish) combo named Alboka (after a kind of hornpipe) and listened to it for the first time in years. One of the livelier tracks is below. It serves, for the moment, to get the Talking Heads' "Life during Wartime" out of my head.

The title of this post is from a piece by Russell Edson, which ends, "Because of all things that might have happened this is the very thing that happens."

Labels:

Notes

Friday, March 13, 2020

Notebook: State of Siege

Major disasters, natural or otherwise, have a way of forcing one not only out of one's routines but out of mental patterns as well. They can reveal a great deal about human character, or (to put it less judgmentally) about human behavior. Camus famously explored this in The Plague, which was the book I instinctively turned to when the first stirrings of the current epidemic (now officially a pandemic) were heard in China. I re-read about a third of the novel, then put it aside for something unrelated I wanted to read, but by the time I was free to get back to it its theme felt too close to home. So instead I went back to fundamentals, first re-reading The Juniper Tree, the superb volume of tales from the Brothers Grimm translated by Lore Segal (and Randall Jarrell), featuring some of Maurice Sendak's most evocative illustrations, and then to Robert Fitzgerald's translation of the Odyssey. Neither of these splendid works has much relevance to the present situation (which is, in part, the point), but if matters of life and death bring one back to essentials, then these are about as essential to me as any books I can think of.

In the meantime, I avoid public places, keep an eye on the food supply (holding up so far), and take walks in the woods, which are now (unlike the forest of folk tales) probably the safest place to be.

Saturday, January 25, 2020

The Causes of Monsters

Ambrose Paré:

The first is the glory of God. The second, his wrath. The third, too great a quantity of semen. The fourth, too small a quantity. The fifth, imagination. The sixth, the narrowness or smallness of the womb. The seventh, the unbecoming sitting position of the mother, who, while pregnant, remains seated too long with her thighs crossed or pressed against her stomach. The eighth, by a fall or blows struck against the stomach of the mother during pregnancy. The ninth, by hereditary or accidental illnesses. The tenth, by the rotting or corruption of the semen. The eleventh, by the mingling or mixture of seed. The twelfth, by the artifice of wandering beggars. The thirteenth, by demons or devils.(Quoted by Leslie Fiedler, Freaks: Myths & Images of the Secret Self)

Labels:

Notes

Monday, December 23, 2019

Notes for a Commonplace Book (27): Lost Powers

Charles Dickens:

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley's Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.

A Christmas Carol

Sunday, December 08, 2019

Notebook: December Blue

Sunday afternoon. Close enough to shake a stick at to fifty years ago, in my lonely and melancholy youth, Joni Mitchell's Blue was the one record I could never listen to enough. Shut in behind dormroom doors, I played it over and over on a clunky portable hi-fi that was already a museum piece by the time I got hold of it. There was nothing unique in this; Blue was a very popular record, at least among the people I hung out with. Mitchell sang beautifully, in spite of whatever minor technical imperfections she might have had at that point in her development, she was beautiful to look at, but most important, nothing she did before or after, not even gems like Hejira (maybe her "masterpiece," overall), and certainly nothing anyone else was doing to that point, seemed to have the same emotional directness. Sparely produced, with just Mitchell's piano, dulcimer, and guitar and a scattering of contributions from other musicians, Blue seemed to suggest that art — whatever art it was you practiced — could, if wielded with honesty and passion, not to mention genius and dedication, cut through all the pretense and posturing and give a glimpse of how we might talk — or sing — to each other if just once we could drop the masks we all carry around with us, both the ones we show to others and the ones we show to the mirror. All an illusion, perhaps, but that's not how it felt at the time.

Anyway, today I got in the car and drove a few miles to a place I like to go hiking, and I brought along a newly-purchased copy of Blue on CD for the ride. I still have my original LP, but I don't really have a functioning turntable and I'm not a big fan of streaming, so this was actually the first time I'd heard the whole thing in many years. (How did I go so long without being able to listen to "A Case of You"? It's hard to figure.) And I have to say it sounded great, probably better than ever since, whatever the merits of the CD vs. vinyl argument, my car's music system is undoubtedly better than my old hi-fi was. And the emotional impact? Yes, it's still there.

Just before our love got lost you saidBut enough of that. It was a seasonably cold but not uncomfortable December afternoon, the skies were partly cloudy, and I hiked for a couple of miles to an overlook I like to visit in the winter when the leaves don't obstruct the views of the nearby reservoir and the surrounding hills. As I neared the top I sensed movement in the sky ahead of me, and looking up I saw an enormous hawk — a red-tail, I think — settle at the top of a bare tree not far off. I switched on my camera but the angle and the light were bad, and before long the hawk leaned forward, leapt off the branch it was perched on, awkwardly bumped another nearby branch, and took flight, quickly disappearing in to the woods behind my shoulder. I finished climbing and sat on the bench that marks the summit for a while, then as I got up to leave I saw the hawk again, in flight above me, and with it a second hawk, probably its mate. The hawks wheeled above me, each in its own tight circle, in effortless command of their element, then gradually drifted further off and out of sight.

"I am as constant as a northern star"

And I said "Constantly in the darkness

Where's that at?

If you want me I'll be in the bar"

On the back of a cartoon coaster

In the blue TV screen light

I drew a map of Canada

— Oh, Canada —

With your face sketched on it twice

On the way home, having traveled several miles by now, I took a back road, and when I neared a small family cemetery adjacent to a horse farm I slowed, thinking it might be a good time and place to see something. Sure enough, as I pulled up, I saw another pair of hawks perched in a tree directly above the cemetery. I switched the camera on even before I opened the car door, but once again the angle was bad and the hawks were too wary. First one then the other took flight, making the same tight circles as the earlier pair, regarding me for a moment or two before likewise moving off.

After I got home, just at dusk, I looked out my kitchen window and saw yet another hawk perched in our peach tree — the one we haven't gotten a peach from in years because of our resident squirrels. This one we've come to think of as an old friend, as we see it in our yard almost every day, and the same or similar hawk has been visiting in the winter for years. It lingered only for a moment, then flew off.

Monday, July 29, 2019

Notes for a Commonplace Book (26)

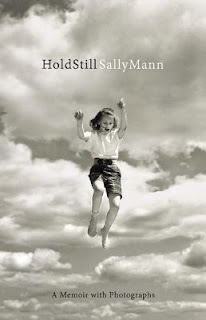

Sally Mann:

At its most accomplished, photographic portraiture approaches the eloquence of oil painting in portraying human character, but when we allow snapshots or mediocre photographic portraits to represent us, we find they not only corrupt memory, they also have a troubling power to distort character and mislead posterity. Catch a person in an awkward moment, in a pose or expression that none of his friends would recognize, and this one mendacious photograph may well outlive all corrective testimony; people will study it for clues to the subject's character long after the death of the last person who could have told them how untrue it is...

It would be an interesting exercise to determine if there's some threshold number of photographs that would guarantee, when studied together so that the signature expressions were revealed and uncharacteristic gestures isolated, a reasonably accurate sense of how a person appeared to those who knew him.

Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs

Saturday, July 27, 2019

Upon the Retina

A Mr. Warner, photographer, on reading an account of Emma Jackson in St. Giles's, addressed a letter to Detective Officer James F. Thompson, informing him that "if the eyes of a murdered person be photographed within a certain time after death, upon the retina will be found depicted the last thing that appeared before them, and that in the present case the features of the murderer would most probably be found thereon." The writer exemplified his statement by the fact of his having, four years ago, taken a negative of the eye of a calf a few hours after death, and, upon a microscopic examination of the same, found depicted thereon the lines of the pavement on the slaughterhouse floor. This negative is unfortunately broken, and the pieces lost.

The Cincinnati Lancet & Observer (1863)

Monday, May 13, 2019

"Mala Cosa" (Cabeza de Vaca)

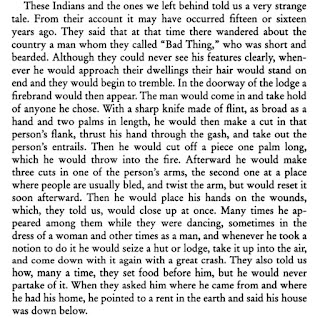

The Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca recounts an incident that was related to him by Native Americans he encountered during his long sojourn across the southern US and northern Mexico:

Narrative of the Narváez Expedition, edited by Harold Augenbraum.

Cabeza de Vaca was one of a handful of survivors of a 16th-century expedition to Florida that went catastrophically wrong. The accuracy of his account of his travels on many points has been questioned, but few things in it are as difficult to believe as the one thing that is unquestionably true, which is that he and three other men did survive eight years wandering among various Native American peoples before finally meeting up with a group of his countrymen near Culiacán in Sinaloa. Along the way he found himself cast in the role of faith healer, and claimed to have performed countless miracles on ailing (and very grateful) Indians.

The passage above has been much pondered. It appears to record some kind of shamanic performance reminiscent in some ways of modern "psychic surgery" cons and fortune-telling bujo scams. How the Indians understood what they told Cabeza de Vaca, and how it differed from what he recorded, is impossible to say. It's the oddest passage in the book.

Sunday, May 12, 2019

On Ants (Thomas Bewick)

"The history and œconomy of these vary curious Insects are (I think) not well known — they appear to manage all their Affairs, with as much forethought & greater industry than Mankind — but to what degree their reasoning & instructive powers extend is yet a mystery — After they have spent a certain time toiling on earth, they then change this abode, get Wings, & soar aloft into the atmosphere — It is not well known what state they undergo, before they assume this new character, nor what becomes of them after."

(Memoirs)

On Being Alone

"As the lodges afforded so little shelter, people began to die, and five Christians quartered on the coast were driven to such extremity that they ate each other until but one remained, who, being left alone, had nobody to eat him." — Cabeza de Vaca

Adapted from the Lakeside Press edition of Narrative of the Narváez Expedition, edited by Harold Augenbraum.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)