Showing posts with label Mark Strand. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Mark Strand. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Reading Matter

Over the past few weeks we've been in the midst of major preparations for an upcoming relocation, but a few days ago I realized that I had gotten a bit ahead of things and packed up almost our entire library, leaving only a handful of books, all of which I'd read before, with two weeks still to go. Fortunately, our local library just had a book sale (partially with our donations), and at this point they're giving away what's left. I stopped by, took a look around, and saw more than I expected. Any other time I might have loaded up, but I had to focus on immediate needs only. I passed, therefore, on two volumes of Chekhov stories, Charlotte Brontë's The Professor, a Mary Braddon novel I knew nothing about, Iris Murdoch's The Sea, The Sea, a Dickens novel I don't own, and several other tempting volumes, and settled on three. The first two were obligatory; Seamus Heaney and Mark Strand have long been two of my favorite poets, and the books I found were slender, which is definitely a plus right now. I've read parts of Sweeney Astray in other Heaney collections, but was only vaguely aware that Strand had written a brief prose work on Edward Hopper. The real find for me, though, was an apparently unread copy of the Bantam edition (c. 1970) of Herman Hesse's last novel, which has been on and off my "to read" list for years. I've actually never read much Hesse, but I'm old enough to remember the time in the 1960s when no sensitive young person's backpack would be complete without a couple of Noonday Press editions of his work. Why this one in particular? Because the premise ("a chronicle of the future about Castalia, an élitist group formed after the chaos of the 20th-century wars") seemed promising, because Gide, Mann, and T. S. Eliot all admired it, and maybe most of all because how can one resist a title as sonorous as Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game) (or in German, Das Glasperlenspiel)? I left a couple of bucks for a donation to the library. It's a no-lose proposition. If Magister Ludi turns out to be a snooze, at least it will help me fall asleep at night.

Sunday, December 11, 2016

The Way It Is (Mark Strand)

(A poem from a different time and different circumstances — but like all good prophecies, it has broken the bounds of whatever impulses first brought it into being.)

THE WAY IT ISImage: Jasper Johns. Mark Strand can be heard reading the poem here.

The world is ugly,

And the people are sad

-Wallace Stevens

I lie in bed.

I toss all night

in the cold unruffled deep

of my sheets and cannot sleep.

My neighbor marches in his room,

wearing the sleek

mask of a hawk with a large beak.

He stands by the window. A violet plume

rises from his helmet's dome.

The moon's light

spills over him like milk and the wind rinses the white

glass bowls of his eyes.

His helmet in a shopping bag,

he sits in the park, waving a small American flag.

He cannot be heard as he moves

behind trees and hedges,

always at the frayed edges

of town, pulling a gun on someone like me. I crouch

under the kitchen table, telling myself

I am a dog, who would kill a dog?

My neighbor's wife comes home.

She walks into the living room,

takes off her clothes, her hair falls down her back.

She seems to wade

through long flat rivers of shade.

The soles of her feet are black.

She kisses her husband's neck

and puts her hands inside his pants.

My neighbors dance.

They roll on the floor, his tongue

is in her ear, his lungs

reek with the swill and weather of hell.

Out on the street people are lying down

with their knees in the air, tears

fill their eyes, ashes

enter their ears.

Their clothes are torn

from their backs. Their faces are worn.

Horsemen are riding around them, telling them why

they should die.

My neighbor's wife calls to me, her mouth is pressed

against the wall behind my bed.

She says, "My husband's dead."

I turn over on my side,

hoping she has not lied.

The walls and ceiling of my room are gray —

the moon's color through the windows of a laundromat.

I close my eyes.

I see myself float

on the dead sea of my bed, falling away,

calling for help, but the vague scream

sticks in my throat.

I see myself in the park

on horseback, surrounded by dark,

leading the armies of peace.

The iron legs of the horse do not bend.

I drop the reins. Where will the turmoil end?

Fleets of taxis stall

in the fog, passengers fall

asleep. Gas pours

from a tricolored stack.

Locking their doors,

people from offices huddle together,

telling the same story over and over.

Everyone who has sold himself wants to buy himself back.

Nothing is done. The night

eats into their limbs

like a blight.

Everything dims.

The future is not what it used to be.

The graves are ready. The dead

shall inherit the dead.

Labels:

Mark Strand,

Poetry,

Prophecy

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Mark Strand (1934-2014)

THE LATE HOUR

A man walks towards town,

a slack breeze smelling of earth

and the raw green of trees blows at his back.

He drags the weight of his passion as if nothing were over,

as if the woman, now curled in bed beside her lover,

still cared for him.

She is awake and stares at scars of light

trapped in the panes of glass.

He stands under her window, calling her name;

he calls all night and it makes no difference.

It will happen again, he will come back wherever she is.

Again he will stand outside and imagine

her eyes opening in the dark

and see her rise to the window and peer down.

Again she will lie awake beside her lover

and hear the voice from somewhere in the dark.

Again the late hour, the moon and stars,

the wounds of night that heal without sound,

again the luminous wind of morning that comes before the sun.

And, finally, without warning or desire,

the lonely and the feckless end.

Labels:

Mark Strand,

Poetry

Sunday, July 06, 2014

The living

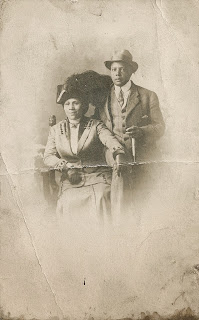

These two faded and stained studio portraits of African-American couples were taken sometime in the early decades of the twentieth century and printed on postcard stock. The one above, which is probably the earlier of the two, is the work of the Flett Studio in Atlantic City, which operated for at least fifteen years or so and must have produced countless similar images. "Mr. & Mrs...," followed by a family name, has been written on the back, but I can't make out the surname. The third figure, standing in the center, may have been the best man at the couple's wedding, or just a relative or friend.

There's even less we can say about the couple below, except that they're dressed to the nines. The studio is unidentified, but the Azo postcard stock used was manufactured from 1904-1918. Like the first postcard, this one was never mailed.

When an artifact is removed from its context without adequate documentation some of its potential for bearing information is lost; we no longer know as much about how it relates to the world that created it. The orphaned photographs above would be much more potent if we knew anything at all about the sitters' identities, life stories, occupations, and families, but people die childless or separated from their families, children have their own lives to lead and can't be bothered, any number of things can sever the thread. Things drift off and go their own ways.

*

The Dead in Frock Coats

In the corner of the living room was an an album of unbearable photos,

many meters high and infinite minutes old,

over which everyone leaned

making fun of the dead in frock coats.

Then a worm began to chew the indifferent coats,

the pages, the inscriptions, and even the dust on the pictures.

The only thing it did not chew was the everlasting sob of life that broke

and broke from those pages.

— Carlos Drummond de Andrade; translation by Mark Strand

Thursday, December 05, 2013

Your Shoulders Hold Up the World

A time comes when you no longer can say: my God.

A time of total cleaning up.

A time when you no longer can say: my love.

Because love proved useless.

And the eyes don’t cry.

And the hands do only rough work.

And the heart is dry.

Women knock at your door in vain, you won’t open.

You remain alone, the light turned off,

and your enormous eyes shine in the dark.

It is obvious you no longer know how to suffer.

And you want nothing from your friends.

Who cares if old age comes, what is old age?

Your shoulders are holding up the world

and it’s lighter than a child’s hand.

Wars, famine, family fights inside buildings

prove only that life goes on

and nobody will ever be free.

Some (the delicate ones) judging the spectacle cruel

will prefer to die.

A time comes when death doesn’t help.

A time comes when life is an order.

Just life, without any escapes.

Poem by Carlos Drummond de Andrade; translation by Mark Strand.

The version above, which I prefer to the revised one included in Strand's Looking for Poetry, is from Souvenir of the Ancient World, published in 1976 by Antaeus Editions in an edition of 500 copies. The typography is by Samuel N. Antupit. I've cropped the page a bit.

Friday, June 18, 2010

Found in translation (Mark Strand)

Who cares if old age comes, what is old age?

Your shoulders are holding up the world

and it's lighter than a child's hand.

Wars, famine, family fights inside buildings

prove only that life goes on

and nobody will ever be free.

Some (the delicate ones) judging the spectacle cruel

will prefer to die.

A time comes when death doesn't help.

A time comes when life is an order.

Just life, without any escapes.

Carlos Drummond de Andrade, lines from "Your Shoulders Hold Up the World." Translation by Mark Strand, from Souvenir of the Ancient World, Antaeus Editions 1976.

We shall drink from the traitor's skull,

we shall wear his teeth as a necklace,

of his bones we shall make flutes,

of his skin we shall make a drum;

later, we'll dance.

"War Song." Translation by Mark Strand, from 18 Poems from the Quechua, Halty Ferguson 1971.

You must look for them

under the drop of wax that buries a word in a book

or the name at the end of a letter

that lies gathering dust.

Look for them

near a lost bottlecap,

near a shoe gone astray in the snow,

near a razorblade left at the edge of a cliff.

Rafael Alberti, lines from "The Dead Angels." Translation by Mark Strand, from The Owl's Insomnia, Atheneum 1973.

The contents of the three books above, with some corrections and additions, were later collected in the omnibus edition below.

Looking for Poetry: Poems by Carlos Drummond de Andrade and Rafael Alberti / Songs from the Quechua, Alfred A. Knopf 2002.

Thursday, February 15, 2007

Souvenir of the Ancient World

Thirty years ago, Dr. Generosity's was a bar on Manhattan's Upper East Side. New York City had Irish bars, punk bars, biker bars, gay bars, sports bars, even a bluegrass bar. Dr. Generosity's was a poetry bar. That fact aside, I don't remember anything particularly distinctive about it, not that I was ever in there more than once or twice. A fairly wide room, when you first walked in, tables spread around, and then the bar itself in the middle towards the back. I don't remember sawdust on the floor or an odor of peanuts, like there was at McSorley's, the long running establishment in the East Village. Were there framed, autographed glossies of famous poets on the walls, smiling in their Oxford shirts and fedoras, suit jackets slung over their shoulders? Probably not.

A guy named Ray Freed, a poet and a waiter, ran a series of poetry readings at the bar for a number of years. He also published some chapbooks under the Doctor Generosity Press imprint; I have one, Spencer Holst's On Demons, with drawings by Beate Wheeler, which was published in 1970. But I didn't buy it at the bar, and I didn't know who Ray Freed was at the time. The only reason I ever knew anything about the place was because a group of friends and I once went there to hear Mark Strand read.

Strand's name first came to my attention when I read a poem of his in an anthology I found on the shelves of my high school library. It was the early '70s, and high school libraries didn't really know how to react to all this youth culture that was suddenly popping up all over, and so they were buying some very strange things with titles like Killing Time: A Guide to Life in the Happy Valley that the librarians probably couldn't make heads or tails of but that sounded like they might have something to do with all these changes that they were hearing about, and it was in that anthology or a similar one that I found Strand's poem “Eating Poetry,” which amused me sufficiently that I went to our local public library, which had a better than average poetry section, and found Strand's collections Reasons for Moving and Darker, both of which I came to know almost verbatim for a while.

I don't remember anymore whether I bought Strand's slender paperback volume of translations from the Brazilian modernist poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade after the reading at Generosity's or before. A little before, I think, but in any case it was around the same time. Souvenir of the Ancient World was published, in an edition of 500 copies printed letterpress by Samuel Antupit, by Antaeus Editions, an imprint briefly used by Daniel Halpern, the publisher of Ecco Press and Antaeus magazine, which, at least in its heyday in the '70s, was about as interesting a literary quarterly as any you could find. I bought it at the Gotham for five dollars; the pencilled price is still on the first page.

So when Strand stepped to the podium to read, on the heels of the much less interesting Howard Moss, a fellow poet who is now long dead, I was probably already familiar with his translations of Drummond, poems like “The Elephant” and “The Phantom Girl of Belo Horizonte,” both of which I'm fairly sure he read that day, or “Quadrille,” which is brief enough to quote in its entirety:

John loved Teresa who loved RaymondStrand was, and most likely still is, a mesmerizing reader: he spoke to the hushed saloon in a sonorous, measured voice, with a delivery that was dramatic without ever being hokey. It didn't hurt that he was tall and good looking and assured; the women must have been lining up for him, maybe some of the men as well. He must have read some of his own work on that particular day, but if so I have no recollection of it; it's the translations he read that have stayed with me when I think back on that day.

who loved Mary who loved Jack who loved Lily

who didn't love anybody.

John went to the United States, Teresa to a convent

Raymond died in an accident, Mary became an old maid,

Jack committed suicide and Lily married J. Pinto Fernandez

who didn't figure into the story.

Regarded as one of the foremost poets Brazil has produced, Carlos Drummond de Andrade was born in Itabira in 1902 and died in Rio de Janeiro in 1987. In addition to Strand's versions, several other English-language translations have been made of selections of his work, with mixed results. There is much that remains untranslated. From what I've been told a good deal of his early work is “proletarian” in nature, not surprising for a lifelong socialist who was raised in a mining town. Though he never abandoned his political affiliation, in later works he turned to more universal matters as well, notably love, longing, and the inevitable approach of oblivion, and it was poems along those lines that Strand picked out to adapt.

Drummond could be very funny, in a sweet, dapper sort of way, and he could be wistful and haunting; frequently he is both at once. At his best, he perfectly captures both the lightness and the weight of being, as in this poem called “Your Shoulders Hold Up the World”:

A time comes when you can no longer say: my God.The interesting thing about that one is that Strand apparently had second thoughts about how he translated it. The problem was that the line “and nobody will ever be free” isn't really what the original (e nem todos se libertaram ainda) means, and when Strand's translations of Drummond de Andrade were reprinted in a later collection (Looking for Poetry, 2002), it was revised to the more accurate, less fatalistic, and infinitely less memorable “and not everybody has freed himself yet,” proving that, in poetry at least, when a translator finds himself caught between sense and sound, he should come down firmly on the side of the latter.

A time of total cleaning up.

A time when we no longer can say: my love.

Because love proved useless.

And the eyes don't cry.

And the hands do only rough work.

And the heart is dry.

Women knock at your door in vain, you won't open.

You remain alone, the light turned off,

and your enormous eyes shine in the dark.

It is obvious you no longer know how to suffer.

And you want nothing from your friends.

Who cares if old age comes, what is old age?

Your shoulders are holding up the world

and it's lighter than a child's hand.

Wars, famine, family fights inside buildings

prove only that life goes on

and nobody will ever be free.

Some (the delicate ones) judging the spectacle cruel

will prefer to die.

A time comes when death doesn't help.

A time comes when life is an order.

Just life, without any escapes.

One of my favorite Strand renditions of Drummond is the poem called “Residue.” It's too long to include in full here, at least under any reasonable interpretation of “fair use,” but basically it's an enumeration of things that are left over, in a variety of contexts, along with the poet's rather desperate wish that, when he is gone, something of himself might remain as well. The poem begins with these two stanzas:

From everything a little remained.And so forth. My favorite bits may be this one:

From my fear. From your disgust.

From stifled cries. From the rose

a little remained.

A little remained of light

caught inside the hat.

In the eyes of the pimp

a little remained of tenderness, very little.

A little remains danglingand of course the final stanza:

in the mouths of rivers,

just a little, and the fish

don't avoid it, which is very unusual.

Still, horribly, from everything a little remains,Those last two lines, I think, pretty much say all there is to say.

under the rhythmic waves

under the clouds and the wind

under the bridges and under the tunnels

under the flames and under the sarcasm

under the phlegm and under the vomit

under the cry from the dungeon, the guy they forgot

under the spectacle and under the scarlet death

under the libraries, asylums, victorious churches

under yourself and under your feet already hard

under the ties of family, the ties of class,

from everything a little always remains.

Sometimes a button. Sometimes a rat.

Saturday, February 12, 2005

Leopardi

There’s a new eatery in town, a kind of delicatessen / restaurant specializing in chicken, and we went in to check it out. While we were eating (I had crab cakes, as I rarely eat poultry), I happened to notice the fabric on the cushions of the bench across from me. Not surprisingly, this was decorated with images of chickens; what was more curious, though, was that there were also several lines of Italian verse, written in an antique hand, repeated through the pattern. The more I looked, the more familiar the words seemed. Now I don’t speak Italian, but I can read it to some extent, and the first line was clear enough:

Dolce e chiara è la notte e senza ventoSomething like: mild and clear is the night and without wind. The remaining lines I had more trouble with, in part because of penmanship, but I could make out the words “luna” and “lontan.”

My first guess was that they night be from Dante. I’ve read the Inferno in English in its entirety, and much of it in Italian, and bits and pieces of the other two canticles in translation. The style seemed right, but not the present tense. Still, the first line seemed very familiar.

When I got home I Googled a few words and quickly found out why I recognized them. They weren’t by Dante, but by Giacomo Leopardi (1798-1837). I’ve never read him, but I did know this:

"Leopardi"That’s a poem by Mark Strand that I’ve always enjoyed, one line of which (“I do not give you any hope. Not even hope”) had, oddly enough, been in my mind just a day or so before I went into the restaurant. I always assumed the poem was an adaptation, but had never come across the original, which, I now know, runs as follows:

The night is warm and clear and without wind.

The stone-white moon waits above the rooftops

and above the nearby river. Every street is still

and the corner lights shine down only upon the hunched shapes of cars.

You are asleep. And sleep gathers in your room

and nothing at this moment bothers you. Jules,

an old wound has opened and I feel the pain of it again.

While you sleep I have gone outside to pay my late respects

to the sky that seems so gentle

and to the world that is not and that says to me:

“I do not give you any hope. Not even hope.”’

Down the street there is the voice of a drunk

singing an unrecognizable song and a car a few blocks off.

Things pass and leave no trace,

and tomorrow will come and the day after,

and whatever our ancestors knew time has taken away.

They are gone and their children are gone

and the great nations are gone.

And the armies are gone that sent clouds of dust and smoke

rolling across Europe. The world is still and we do not hear them.

Once when I was a boy, and the birthday I had waited for

was over, I lay on my bed, awake and miserable, and very late

that night the sound of someone’s voice singing down a side street,

dying little by little into the distance,

wounded me, as this does now.

XIII - La sera del dì di fiestaI haven't had time to make (or better, find) a full translation, though I've looked it over enough to see both differences and similarities between Strand's version and the original. Strange drift and mingling of circumstance, that reveals the source of a favorite poem through the upholstery of a chicken restaurant.

Dolce e chiara è la notte e senza vento,

E queta sovra i tetti e in mezzo agli orti

Posa la luna, e di lontan rivela

Serena ogni montagna. O donna mia,

Già tace ogni sentiero, e pei balconi

Rara traluce la notturna lampa:

Tu dormi, che t’accolse agevol sonno

Nelle tue chete stanze; e non ti morde

Cura nessuna; e già non sai nè pensi

Quanta piaga m’apristi in mezzo al petto.

Tu dormi: io questo ciel, che sì benigno

Appare in vista, a salutar m’affaccio,

E l’antica natura onnipossente,

Che mi fece all’affanno. A te la speme

Nego, mi disse, anche la speme; e d’altro

Non brillin gli occhi tuoi se non di pianto.

Questo dì fu solenne: or da’ trastulli

Prendi riposo; e forse ti rimembra

In sogno a quanti oggi piacesti, e quanti

Piacquero a te: non io, non già, ch’io speri,

Al pensier ti ricorro. Intanto io chieggo

Quanto a viver mi resti, e qui per terra

Mi getto, e grido, e fremo. Oh giorni orrendi

In così verde etate! Ahi, per la via

Odo non lunge il solitario canto

Dell’artigian, che riede a tarda notte,

Dopo i sollazzi, al suo povero ostello;

E fieramente mi si stringe il core,

A pensar come tutto al mondo passa,

E quasi orma non lascia. Ecco è fuggito

Il dì festivo, ed al festivo il giorno

Volgar succede, e se ne porta il tempo

Ogni umano accidente. Or dov’è il suono

Di que’ popoli antichi? or dov’è il grido

De’ nostri avi famosi, e il grande impero

Di quella Roma, e l’armi, e il fragorio

Che n’andò per la terra e l’oceano?

Tutto è pace e silenzio, e tutto posa

Il mondo, e più di lor non si ragiona.

Nella mia prima età, quando s’aspetta

Bramosamente il dì festivo, or poscia

Ch’egli era spento, io doloroso, in veglia,

Premea le piume; ed alla tarda notte

Un canto che s’udia per li sentieri

Lontanando morire a poco a poco,

Già similmente mi stringeva il core.

Postscript: The restaurant mentioned above has since closed. However, it fascinates me to know that someone has translated Strand's version back into Italian: La sera è calma e limpida e senza vento / La luna bianca come pietra aspetta sopra i tetti...

Labels:

Leopardi,

Mark Strand,

Poetry,

Translation

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)