When I first read this 1978 novel by Georges Perec in David Bellos's translation years ago I recall being entertained but also perhaps a bit underwhelmed. This summer I'm reading it in the original (with the translation on hand as a crib) as a way to keep up my French. In some ways it's ideal for the purpose. It's made up of fairly short, self-contained chapters that I can read at a relaxed pace of one or two a day, and it's not particularly slangy or conversational (street French not being something I'm up on). The grammar I can handle; the hard part is the vocabulary for material objects (clothes, home furnishings, tools) which Perec delights in ennumerating. (In fact the cataloguing of objects was part of his compositional method.) These are, as it turns out, the very things where my

English vocabulary is weakest; thus when Perec refers to an

aumônière, I am little wiser when I turn to Bellos and find that this is "a Dorothy bag." My eyes begin to glaze over when Perec, at his most maniacal, devotes several pages to the contents of a catalog from a hardware manufacturer. Fortunately, such extreme moments are rare.

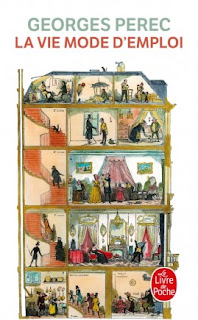

For those unfamiliar with the book,

La vie mode d'emploi captures a snapshot of the inhabitants and furnishings of a Paris apartment building at one instant in June 1975. In addition to describing them synchronically, he also moves back in time liberally in order to narrate the stories of the present and former denizens of the building. There's also a frame tale involving an expatriate Englishman named Bartlebooth who wanders the world for twenty years painting harbor scenes, which he sends home and has made into jigsaw puzzles. Puzzles and games fascinated Perec, and the writing of the novel was itself structured by the use of various constraints and procedures, such as a "knight's tour" in chess, in which the knight visits every space on the chessboard exactly once. But arguably the parts are more interesting than the whole.

Comparing the two versions raises new puzzles. Why, for instance, in the list of paintings created by a tenant named Franz Hutting, did Bellos translate

14 Maximilien, débarquant à Mexico, s'enfourne élégamment onze tortillas

as

14 Maximilian lands in Mexico and daintily scoffs four nelumbia and eleven tortillas

and for that matter what on earth are "nelumbia"? Why does

21 Le docteur Lajoie est radié de l'ordre des médecins pour avoir déclaré en public que William Randolph Hearst,

sortant d'une projection de Citizen Kane, aurait monnayé l'assasinat d'Orson Welles

become

21 Dr LaJoie is struck off the medical register for having stated, in front of Ray Monk, Ken O'Leary, and others that, after seeing Citizen Kane, William Randolph Hearst had put a price on Orson Welles's head

with the parts in bold (my emphasis) being apparently gratuitous additions by the translator?

As it turns out, there is method to Bellos's changes. According to a table available

here, each painting description in the original conceals the name of one of Perec's friends and associates. Thus "s'en

fourne élégamment" hides (Paul) Fournel, which Bellos has reproduced with the mysterious "

four nelumbia." Similarly, "

Kane, aurait" reveals (Raymond) Queneau, prompting Bellos''s "

Ray Monk, Ken O." (Harry Mathews, by the way, is tucked into "Joseph d'

Arimathie ou Zarathoustra.")

These diabolical devices, of which there must be many examples throughout the novel, add to the book's fascination, but also provoke some frustration. What else, one wonders, is one overlooking as one reads innocently along?