Dalkey Archive Press / Deep Vellum Publishing is re-issuing seven books by Harry Mathews, according to Publishers Weekly, which notes that "the reissued editions will feature new cover designs and never-before-seen archival photographs of the author, as well as introductions by such writers as Jonathan Lethem, Lucy Sante, and Ed Park." Three of the volumes will appear this year, with the others scheduled over the next few years.

I can't help adding, given the current climate in the nonprofit world, "if the money holds out." It's good to see Mathews getting respectful attention, although I wonder how many potential readers of his work are out there who don't already own earlier editions.

Showing posts with label Harry Mathews. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Harry Mathews. Show all posts

Saturday, May 24, 2025

Tuesday, June 11, 2024

Materia medica

Harry Mathews, summarizing the medical theories of the "philosopher-dentist" R. King Dri:

The human body, richest of nature’s fruits, is not a single organism made of constituent parts, but an assemblage of entities on whose voluntary collaboration the functioning of the whole depends. “The body is analogous to a political confederation—not to the federation as is normally supposed.” Every entity within the body is endowed with its own psyche, more or less developed in awareness and self-consciousness. Aching teeth can be compared to temperamental six-year-old children; an impotent penis to an adolescent girl who must be cajoled out of her sulkiness. The most developed entity is the heart, which does not govern the body but presides over it with loving persuasiveness, like an experienced but still vigorous father at the center of a household of relatives and pets. Health exists when the various entities are happy, for they then perform their roles properly and co-operate with one another. Disease appears when some member of the organism rejects its vocation. Medicine intervenes to bring the wayward member back to its place in the body’s society. At best the heart makes its own medicine, convincing the rebel of its love by addressing it sympathetically; but a doctor is often needed to encourage the communion of heart and member, and sometimes, when the patient has surrendered to unconsciousness or despair, to speak for the heart itself.Raymond Roussel:

Tlooth

Paracelsus regarded each component of the human body as a thinking individual with an observing mind of its own, which enabled it to know itself better than anyone else could do. When it became ill, it knew what remedy could cure it and, in order to make its priceless revelation, only awaited questions cleverly put by a shrewd doctor who would wisely limit his true role to this.I had read Tlooth many times before picking up Locus Solus, though Mathews always made clear his debt to Roussel. As far as I can tell, the attribution to Paracelsus is spurious, although the Swiss doctor did have some curious (and progressive) ideas. The translation of the Roussel, from 1970, is credited to the mysterious Rupert Copeland Cuningham, evidently a pseudonym. An earlier version of the passage from Tlooth can be found at the website of the Paris Review. The book version incorporates numerous minor changes, most of them clear improvements; the word "communion" in the last line, for example, was originally "communication." The name R. King Dri is probably a pun or anagram of some sort.

Locus Solus

Wednesday, February 01, 2023

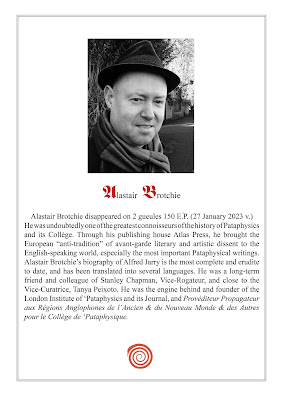

2 gueles 150 E.P.

The writer and publisher Alastair Brotchie has died, according to social media announcements by the Atlas Press, of which he was the proprietor, and the London Institute of Pataphysics, of which he was a guiding spirit and "Secretary of Issuance." The date of his "disappearance" is given, according to the Pataphysical calendar, in the title of this post; according to the Gregorian calendar it was on January 27th of this year.

Brotchie's biography of Alfred Jarry has been near the top of my list of books to read for several years, but I've never quite gotten around to it, in part because our local library system doesn't own a copy. I do have a copy of the Oulipo Compendium he edited with Harry Mathews.

Pataphysics, founded by Jarry, has been defined as "the science of imaginary solutions," and you may make of that what you will. Shortly before the pandemic broke out I took a trip into Manhattan, in part to see the outstanding exhibition at the Morgan Library devoted to Jarry. One can only wonder what he would have made of such a venue for his work, but I like to think he would have been amused. I haven't been back to the city since.

My condolences to Brotchie's family and friends.

Update: The Guardian now has an obituary of Brotchie written by his friend Peter Blegvad.

Brotchie's biography of Alfred Jarry has been near the top of my list of books to read for several years, but I've never quite gotten around to it, in part because our local library system doesn't own a copy. I do have a copy of the Oulipo Compendium he edited with Harry Mathews.

Pataphysics, founded by Jarry, has been defined as "the science of imaginary solutions," and you may make of that what you will. Shortly before the pandemic broke out I took a trip into Manhattan, in part to see the outstanding exhibition at the Morgan Library devoted to Jarry. One can only wonder what he would have made of such a venue for his work, but I like to think he would have been amused. I haven't been back to the city since.

My condolences to Brotchie's family and friends.

Update: The Guardian now has an obituary of Brotchie written by his friend Peter Blegvad.

Monday, August 01, 2022

11 Rue Simon-Crubellier

When I first read this 1978 novel by Georges Perec in David Bellos's translation years ago I recall being entertained but also perhaps a bit underwhelmed. This summer I'm reading it in the original (with the translation on hand as a crib) as a way to keep up my French. In some ways it's ideal for the purpose. It's made up of fairly short, self-contained chapters that I can read at a relaxed pace of one or two a day, and it's not particularly slangy or conversational (street French not being something I'm up on). The grammar I can handle; the hard part is the vocabulary for material objects (clothes, home furnishings, tools) which Perec delights in ennumerating. (In fact the cataloguing of objects was part of his compositional method.) These are, as it turns out, the very things where my English vocabulary is weakest; thus when Perec refers to an aumônière, I am little wiser when I turn to Bellos and find that this is "a Dorothy bag." My eyes begin to glaze over when Perec, at his most maniacal, devotes several pages to the contents of a catalog from a hardware manufacturer. Fortunately, such extreme moments are rare.

For those unfamiliar with the book, La vie mode d'emploi captures a snapshot of the inhabitants and furnishings of a Paris apartment building at one instant in June 1975. In addition to describing them synchronically, he also moves back in time liberally in order to narrate the stories of the present and former denizens of the building. There's also a frame tale involving an expatriate Englishman named Bartlebooth who wanders the world for twenty years painting harbor scenes, which he sends home and has made into jigsaw puzzles. Puzzles and games fascinated Perec, and the writing of the novel was itself structured by the use of various constraints and procedures, such as a "knight's tour" in chess, in which the knight visits every space on the chessboard exactly once. But arguably the parts are more interesting than the whole.

Comparing the two versions raises new puzzles. Why, for instance, in the list of paintings created by a tenant named Franz Hutting, did Bellos translate

As it turns out, there is method to Bellos's changes. According to a table available here, each painting description in the original conceals the name of one of Perec's friends and associates. Thus "s'enfourne élégamment" hides (Paul) Fournel, which Bellos has reproduced with the mysterious "four nelumbia." Similarly, "Kane, aurait" reveals (Raymond) Queneau, prompting Bellos''s "Ray Monk, Ken O." (Harry Mathews, by the way, is tucked into "Joseph d'Arimathie ou Zarathoustra.")

These diabolical devices, of which there must be many examples throughout the novel, add to the book's fascination, but also provoke some frustration. What else, one wonders, is one overlooking as one reads innocently along?

For those unfamiliar with the book, La vie mode d'emploi captures a snapshot of the inhabitants and furnishings of a Paris apartment building at one instant in June 1975. In addition to describing them synchronically, he also moves back in time liberally in order to narrate the stories of the present and former denizens of the building. There's also a frame tale involving an expatriate Englishman named Bartlebooth who wanders the world for twenty years painting harbor scenes, which he sends home and has made into jigsaw puzzles. Puzzles and games fascinated Perec, and the writing of the novel was itself structured by the use of various constraints and procedures, such as a "knight's tour" in chess, in which the knight visits every space on the chessboard exactly once. But arguably the parts are more interesting than the whole.

Comparing the two versions raises new puzzles. Why, for instance, in the list of paintings created by a tenant named Franz Hutting, did Bellos translate

14 Maximilien, débarquant à Mexico, s'enfourne élégamment onze tortillasas

14 Maximilian lands in Mexico and daintily scoffs four nelumbia and eleven tortillasand for that matter what on earth are "nelumbia"? Why does

21 Le docteur Lajoie est radié de l'ordre des médecins pour avoir déclaré en public que William Randolph Hearst, sortant d'une projection de Citizen Kane, aurait monnayé l'assasinat d'Orson Wellesbecome

21 Dr LaJoie is struck off the medical register for having stated, in front of Ray Monk, Ken O'Leary, and others that, after seeing Citizen Kane, William Randolph Hearst had put a price on Orson Welles's headwith the parts in bold (my emphasis) being apparently gratuitous additions by the translator?

As it turns out, there is method to Bellos's changes. According to a table available here, each painting description in the original conceals the name of one of Perec's friends and associates. Thus "s'enfourne élégamment" hides (Paul) Fournel, which Bellos has reproduced with the mysterious "four nelumbia." Similarly, "Kane, aurait" reveals (Raymond) Queneau, prompting Bellos''s "Ray Monk, Ken O." (Harry Mathews, by the way, is tucked into "Joseph d'Arimathie ou Zarathoustra.")

These diabolical devices, of which there must be many examples throughout the novel, add to the book's fascination, but also provoke some frustration. What else, one wonders, is one overlooking as one reads innocently along?

Monday, December 13, 2021

Buffon's Ounce, the lonza leggera, and The Long Walk

Slawomir Rawicz was a Polish military officer in World War II who in the 1950s dictated to a ghost-writer a stirring account of how he and several companions engineered their escape from a Siberian prison camp, crossed the Gobi Desert, and then trekked over the Himalayas to safety in British India. Among the incidents he related was a close encounter with two Abominable Snowmen. Just by itself that latter claim might have raised eyebrows, and in fact the consensus now is that Rawicz's account, which was published in 1956 as The Long Walk, celebrated for decades as both an adventure yarn and an anti-Soviet testimony, and eventually filmed (as The Way Back) by Peter Weir, is essentially fictional. Still, at least it makes a good story.

I'm not the only one who has noted the likely influence of Rawicz's book on Harry Mathews's novel Tlooth, which came out in book form in 1966 after having been serialized in the Paris Review. Tlooth, like The Long Walk, describes a clever escape from Siberia and a southward journey over the Himalayas. (It differs from the earlier book in involving, among other things, dental malpractice, obscure religious denominations, and an exploding baseball.) There are no yetis in Mathews's book, but there is a cryptic if not cryptozoological sighting in a chapter entitled "Buffon's Ounce." The narrator and his companions reach a high pass:

But there's one more weird twist to this convoluted story. Tlooth was published, as I said, in the Paris Review. Its author jokingly claimed that he was often mistakenly assumed to have been in the CIA, and even wrote a novel (My Life in CIA) based on that premise. One reason that Mathews might have plausibly been assumed to have been in the CIA was his connection with the Paris Review, one of whose co-founders, the writer Peter Matthiessen, later admitted that he had used the magazine as cover for his CIA work. In 1979 Matthiessen would win the National Book Award for a book about his travels in the Himalayas. Its title was The Snow Leopard.

* And thus a tale for another time: Jefferson's obsession with the remains of the extinct American mastodon, Charles Willson Peale's excavation of a specimen of the same, Peale's painting of his excavation, an album called Kew. Rhone inspired by the painting, a book, celebrating the album, that includes a contribution by Harry Mathews...

I'm not the only one who has noted the likely influence of Rawicz's book on Harry Mathews's novel Tlooth, which came out in book form in 1966 after having been serialized in the Paris Review. Tlooth, like The Long Walk, describes a clever escape from Siberia and a southward journey over the Himalayas. (It differs from the earlier book in involving, among other things, dental malpractice, obscure religious denominations, and an exploding baseball.) There are no yetis in Mathews's book, but there is a cryptic if not cryptozoological sighting in a chapter entitled "Buffon's Ounce." The narrator and his companions reach a high pass:

There, in midafternoon, a shout stopped us.That's the last we hear of the animal. The Italian line is from the first canto of the Inferno, where Dante is brought up short by three beasts, the third of which is "a lithe and very swift leopard" — except that what Dante actually meant by lonza has been long debated. Which brings us to the meaning, otherwise unexplained, of the title of the chapter. "Buffon" is Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, a French naturalist known, among other things, for disparaging the animals of the New World as being inferior to those of the Old (to the fury of Jefferson*), and "ounce" (or in French, "once") is an obsolete word for a large wild feline, based on an etymological misunderstanding of a derivitive of the Latin word "lynx." (A form like "lonza" was misinterpreted as "l'onza.) What Buffon described — he was the first Westerner to do so — was in fact the snow leopard, shown above in an 18th-century engraving based on his work.

"Look!" Beverley pointed uphill.

I saw a pale spotted creature clamber catfashion over snows into the rocks.

Robin remarked, "Una lonza leggiera e presta molto."

But there's one more weird twist to this convoluted story. Tlooth was published, as I said, in the Paris Review. Its author jokingly claimed that he was often mistakenly assumed to have been in the CIA, and even wrote a novel (My Life in CIA) based on that premise. One reason that Mathews might have plausibly been assumed to have been in the CIA was his connection with the Paris Review, one of whose co-founders, the writer Peter Matthiessen, later admitted that he had used the magazine as cover for his CIA work. In 1979 Matthiessen would win the National Book Award for a book about his travels in the Himalayas. Its title was The Snow Leopard.

* And thus a tale for another time: Jefferson's obsession with the remains of the extinct American mastodon, Charles Willson Peale's excavation of a specimen of the same, Peale's painting of his excavation, an album called Kew. Rhone inspired by the painting, a book, celebrating the album, that includes a contribution by Harry Mathews...

Sunday, July 30, 2017

Coming Attractions

What I'll be reading this Fall: Mike Wallace's Greater Gotham, the long-awaited sequel to Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, the definitive history of the city that Wallace (no relation to the CBS correspondent) co-wrote with Edwin G. Burrows and published in 1999. Though slated to be slightly shorter than the first installment (which ran, with index, to nearly 1,400 pages), this follow-up covers a span of a mere twenty-one years — which, as it happens, corresponds fairly exactly to the period in the city's history that interests me most. Good news, even if it does leave one wondering when — if ever — the third installment will appear. A release date of September or October is projected for this one.

Also on the horizon: Harry Mathews's last novel, The Solitary Twin, is scheduled to be published by New Directions in March 2018.

Saturday, February 18, 2017

Refuge (Harry Mathews)

The attractions: solitude and secrecy—the orchard in the hills like a kingdom, the forbidden manufacture of liquor a prowess all my own, blessed with the contemplation of fir and beech, wild plum and cherry, and the company of the shy marten and jay as well as of cocky wrens and wagtails; the challenges of hiking, labor, and barter; the relief of exhaustion; the reassurance of a smartly contracted horizon; the refuge of my dwelling, small, neat, and warm, with its pots of flowering wallpepper and thyme, my pet dormouse staring around the thyme, and the new ikon over my writing stool whose wood shines in the clear frame of stenchless fresh oil; soft if short hours in the lamplight, pen in hand, showered with the random amber of phantasmal summers, abundances, triumphs of art; visits from the widow.The title section of the late Harry Mathews's Armenian Papers: Poems 1954-1984 purports to be an adaptation of an Italian translation of a lost Armenian original, "a manuscript of medieval poems that had mysteriously and irrevocably disappeared during the decade preceding the First World War," whose existence was revealed to Mathews, Marie Chaix, and David Kalstone in 1979 during a visit to the Armenian monastery of San Lazzaro in Venice by a certain Father Gomidas. San Lazzaro does in fact exist, and the three writers may well have made such a visit; the rest is made up out of whole cloth, perhaps inspired by a package of papier d'Arménie.

Thursday, January 26, 2017

Harry Mathews (1930-2017)

The writer Harry Mathews died yesterday. Weirdly, I found out because I looked him up to see what he was up to, well knowing that he was getting up there in years. I don't have anything particularly profound to say at the moment except what I would have said to Harry if I ever had the opportunity (we never met): "Thanks for writing those books." The obituary notices so far are mostly in French, but the Paris Review has a brief note and provides the one piece of good news: he completed a forthcoming new novel before he died.

My post from a few years back is here: Permutations of Mathews. Worth a listen is Isaiah Sheffer's hilarious reading of Mathews's story "Country Cooking from Central France: Roast Boned Rolled Stuffed Shoulder of Lamb (Farce Double)" (you can skip ahead to 1:10 or so).

Monday, September 28, 2015

Oracles

Rabelais:

Bacbuc threw something into the fountain, and suddenly the water began to boil fiercely, as the great cauldron at Bourgueil does when there is a high feast there. Panurge was listening in silence with one ear, and Bacbuc was still kneeling beside him, when there issued from the sacred Bottle a noise such as bees make that are bred in the flesh of a young bull slain and dressed according to the skillful method of Aristaeus, or such as is made by a bolt when a cross-bow is fired, or by a sharp shower of rain suddenly falling in summer. Then this one word was heard: Trink.Translation by J. M. Cohen (1955).

'By God almighty,' cried Panurge, 'it's broken or cracked, I'll swear. That is the sound that glass bottles make in our country when they burst beside the fire.'

Then Bacbuc arose and, putting her hands gently behind Panurge's arms, said to him: 'Give thanks to heaven, my friend. You have good reason to. For you have most speedily received the verdict of the divine Bottle; and it is the most joyous, the most divine, and the most certain answer that I have heard from it yet, in all the time I have ministered to this most sacred Oracle.'

Harry Mathews:

Harry Mathews:

Consulting his watch, he continued: "The hour is right, you won't have to wait. Here's what you do: take the boot off your right foot, and your sock if you're wearing one, and stick your leg in up to the knee. Keep it there for a minute plus eight seconds, which I'll time for you; then remove it quickly. The prophecy will follow."I've found only passing mention of the possible influence of Rabelais on Harry Mathews (truth to tell, there isn't all that much critical literature on the latter), but here the inspiration seems clear enough. Since I've been reading Mathews for decades but Rabelais only recently, this gives his novels an interesting new light — as does the description of the intricately contrived, magnetically opened temple in Chapter 37 of Le cinquième livre de Pantagruel, wherein is engraved the motto "All Things Move to their End." Readers of the last chapter of The Conversions will no doubt know what I mean.

I did as I was told, although I could not believe we had reached the bog. It was nearly dark.

Supporting me by my left elbow, the Count said, "Ready? Now," and I stepped forward. My foot sank slowly into heavy mud still warm from the sun.

A minute passed. Renée counted the final seconds: "...seven, eight," and I extracted my leg from the mire.

Following the Count's example, I knelt down. In a moment there was perhaps a liquid murmur or rumble and out of the ooze, as if a capacious ball of sound had forced its passage to the air, a voice distinctly gasped,

"Tlooth."

The mud recovered its smoothness. After a pause, the Count shook his head and said, "Aha! Rather enigmatic. But there won't be more. And," he chuckled, "you can't try again for another year."

N. B. J. M. Cohen regarded the chapters describing the Temple of the Bottle as "so dull that it would be charitable to ascribe them to another hand." Without weighing in on the debate over the authorship of parts of the cinquième livre, I can't quite agree. They're certainly bizarre, but maybe they just were ahead of their time.

Friday, August 07, 2015

Funeral Rites Revisited

In a 2013 post I juxtaposed the self-glorifying funeral instructions left by Oscar Thibault, the patriarch in Roger Martin du Gard's multi-volume novel Les Thibaults, with the intricate and preposterous obsequies commanded by the "wealthy eccentric" Grent Oude Wayl in Harry Mathews's 1962 novel The Conversions. Above is one more: Willie McTell's 1956 rendering of "Dyin' Crapshooter's Blues," which tells how the last wishes of the gambler Jesse Williams were carried out.

Though McTell recorded the song three times, the version above being the last, his repeated claim to have written it is open to question. Elements of the lyrics can be traced back to at least the 18th century (blues scholar Max Haymes has untangled some of the tangled strands of its prehistory), and Robert W. Harwood has attributed the song's creation in the form in which we know it to the elusive African-American composer and bandleader Porter Grainger. Be that as it may, there is no doubt that McTell's versions are the definitive performances.

Saturday, March 09, 2013

Re-reading Martin du Gard (VI): Funeral Rites

After a long illness, Oscar Thibault, the grand paterfamilias of the Thibault family, has died, and among his papers his son Antoine finds instructions for his funeral which demonstrate the same robust mixture of self-regard, compulsion for control, pious embarrassment, and rationalization that had characterized Oscar's entire adult life. In the version below I have retranslated the funeral instructions but used some of Stuart Gilbert's readings from the original translation. The "Institution" at Crouy is a reform school, and the "pupils" could equally well be called "inmates."

I desire that after a low mass has been said at Saint Thomas Aquinas, my parish, my body be brought to Crouy. I desire that my obsequies be celebrated there in the Institution's chapel, in the presence of all the pupils. I desire that, in contrast to the service at Saint Thomas Aquinas, the funeral service shall be carried out with all the dignity with which it may please the Committee to honor my mortal remains. I would like to be led to my last resting place by the representatives of the charitable works that have, over the course of many years, accepted the good offices of my devotion, as well as by a delegation of that Institut de France of which I have been so proud to have been welcomed as a member. I also wish, if the regulations permit, that my rank in the Order of the Legion of Honor might assure me of a military salute from that Army which I have always defended in all my words, writings, and my votes as a citizen. Finally, I wish that those who express the desire to pronounce a few parting words over my grave be permitted to do so without restriction.This is all, by the way, prefatory to the "detailed instructions" Antoine also finds, which Martin du Gard spares us.

In writing this, it is not that I hold any illusion about the vanity of these posthumous glories. I am already filled with anxiety at the thought of having one day to make my reckoning before the Supreme Tribunal. Nevertheless, after exposing myself to the illumination of meditation and prayer, it seems to me, that in those circumstances, the true duty consists in imposing silence on a sterile humility, and to arrange matters so that, at the time of my death, my existence may, if it please God, be held up one last time as an example, with the aim of inspiring other great Christians among our grand French bourgeoisie to devote themselves to the service of the Faith and Catholic charity.

I can't help thinking that it would have been amusing if Harry Mathews had these instructions in the back of his mind as he drew up, for The Conversions, the elaborate Last Will and Testament of Grent Oude Wayl, which decreed, among other things:

That the organist of St. James's Church, Madison Avenue and 71st Street, Manhattan, choose a suitable musical composition to accompany the departure of my remains to their place of burial; that the score of this composition (notes, rests, clefs, key and time signatures, and all indications of speed, phasing and dynamics) be reproduced at fifteen times its printed size in the form of pancakes; and that these cakes be obligatorily eaten by any and all such persons who attend the reading of this my Last Will and Testament, excepting those specifically invited thereto. (In the event of non-compliance with this provision, I have instructed my faithful servant Miss Gabrielle Dryrein, of 2980 Valentine Avenue, The Bronx, to give to the press all information kept in my files concerning liable parties.)I'll leave the unexpected outcome of Mr. Wayl's funeral for future readers of The Conversions to discover, but as for the pancakes, "The organist at St. James's, who had planned a twenty-nine minute Tragic Rhapsody of Widor, was warned of the consequences and changed to a unison version of O God Our Help in Ages Past; so that the forced feeders had only twenty-eight notes to swallow between them, and — the hymn being all in wholenotes and halfnotes — hollow ones at that."

Saturday, September 08, 2012

Briefly noted (Harry Mathews)

An online journal called The Quarterly Conversation is devoting a good part of its Fall 2012 issue (#29) to a special feature entitled An American in Oulipo: The Harry Mathews Symposium, including separate articles about The Conversions, the first three novels considered collectively, Cigarettes, My Life in CIA, and other works. As far as I can tell the journal has no print edition, which is a drag since I find reading more than three or four paragraphs at a time on a computer screen to be uncongenial (says the blogger). Still, it's nice to see that there's still some interest out there in Mathews's work.

Saturday, March 26, 2011

Permutations of Mathews

The wealthy amateur Grent Wayl invited me to his New York house for an evening's diversion...

I picked up this volume in the Strand Bookstore in the mid-1970s, and it's been a favorite ever since. They had a stack of them that day, laid out on a table among the hardcover Cortázars and other good things that were being remaindered in those days, and I've always regretted that I didn't buy the whole lot and bring them home so that they could live together happily and maybe even multiply.

I don't believe I had ever heard of Harry Mathews at the time. It wouldn't have been likely; he wasn't part of any recognized "canon," not even an incipient "postmodern" one, and they certainly weren't writing about him in the book sections of the magazines I was reading. The cover looked interesting -- there was that wonderful Jim Dine illustration with a strangely animate pair of scissors whose blades seemed to be oriented in defiance of their intended purpose -- but I think I hesitated at first.

For one thing, there was the matter of the title. In addition to the obscure allusion to Kafka's equally obscure odradek, and the puzzling issue of how a stadium could "sink," there was the subversive notion embodied in the words "... and Other Novels." A "novel," at least a serious novel, was supposed to be "total," to encompass multiple levels of reality in some sort of approximation of life itself; it wasn't supposed to admit the possibility of being just one invention among several. The blurb on the back, though, was pretty promising:

For several years Harry Mathews has enjoyed a growing following among college students, artists, other poets and writers, and fans of the obscure who have never been able to buy his books. This volume is meant to satisfy their needs: it brings together his two out-of-print novels -- The Conversions (1962) and Tlooth (1966) -- and his latest fiction, The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium. Mathews' work is virtually indescribable in brief. His is a genius of wild invention presented in a kind of meticulous deadpan narration that leaves the reader howling, amazed, and exhilarated. Beneath the brilliance of his elegant language and intricate constructions, Mathews is writing avant-garde fiction of starting originality. This omnibus volume gives ample evidence of Mathews' significance in the world of contemporary literature: it is time for a major assessment of his extraordinary work"College students, artists, other poets and writers, and fans of the obscure" seemed to fit me fairly well (except for the "artists" part -- neither then nor now have I been able to draw a line) and I plunked down my two or three dollars and took the book home.

Harry Mathews is a bit better known today, having published two or three more novels (depending on whether you think My Life in CIA is fiction or not), several volumes of short stories and poetry, and various essays and the like, and he's even been the subject of a monograph in the Twayne's United States Authors series, but in spite of all that I suspect that even now most readers of "serious fiction" -- whatever that means these days -- still wouldn't know his name. To a degree that's understandable -- initially, at least, his novels can appear to be as disorienting as the cover of this book -- but it's also a shame, because at his best Mathews is a hoot, a master storyteller whose books are crammed with ingenious inventions, jokes, red herrings, anagrams*, and eccentricities but who is also just downright entertaining. "Meticulous deadpan narration" is right on the money; his narrators share a kind of tunnel vision diametrically opposed to the "realistic" psychology and self-awareness that have largely characterized the modern American novel. It is the reader, not the narrator, who undergoes development. Even the curious title of one of these novels -- The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium -- reveals something its epistolary narrators never learn.

Describing any of these novels in this space is a hopeless task; Wikipedia has brief summaries and Warren Leamon's Harry Mathews in the Twayne's series provides quite detailed ones. All three have to do with improbable quests of some kind, either for treasure, for knowledge, or, in the case of Tlooth, for revenge, but it is the diversions and digressions, the hidden pitfalls, that lay along the route that make them so enjoyable. I've read each of the three components of this volume three or four times -- The Conversions maybe six times -- and I'm still discovering things in them I never noticed before. Mathews' technique consists not of revealing secrets, but of constructing a labyrinth so intricate that even as we progress through it the presumptive "solution" to its enigmas only recedes further into the distance.

The Conversions first saw print in the pages of Locus Solus, a short-lived literary magazine Mathews published himself with money he obtained from an inheritance. It was then published in full** in The Paris Review (#27) and in book form by Random House in 1962. Both Tlooth and Odradek were also originally serialized in The Paris Review.

The omnibus edition from Harper & Row is long out-of-print. Carcanet in the UK put out individual editions in the 1980s, which have since been superseded by those published by Dalkey Archive Press. Reading the three novels together, and in chronological order, though not necessary, is still the best way to enjoy them.

The bibliography of writings by and about Harry Mathews is now quite substantial, but in addition to Leamon's dated but still-valuable critical study the book-length issue of The Review of Contemporary Fiction (Fall 1987; Vol. VII, No. 3) devoted to Mathews deserves particular mention. The Paris Review (No. 180) featured an excellent interview with Mathews as part of its longstanding "Art of Fiction" series, and that interview can also be read online.

*To cite just one, the puzzling "Mundorys Lorsea" of The Conversions transforms into "Raymond Roussel," although I am also fond of the possibilities of "snarly dormouse."

** Not quite correct; some sections of the novel were summarized in the version printed in the Paris Review.

Tuesday, March 22, 2011

Notes for a Commonplace Book (8)

From an interview with Harry Mathews:

INTERVIEWER

Did Ashbery introduce you to any writers whose work you did read?

MATHEWS

Yes, thanks to John I began reading Raymond Roussel. Roussel had methodical approaches to writing fiction that completely excluded psychology. In the American novel, what else is there? If you don't have psychology, people don't see the words on the page. What was really holding me up was this idea that you had to have character development, relationships, and that this was the substance of the novel. Indeed, it is the substance of many novels, including extraordinary ones. But I had tried writing works involving psychology and characters and all that, and the results were terrible. In Roussel I discovered you could write prose the way you do poetry. You don’t approach it from the idea that what you have to say is inside you. It's a materialist approach, for want of a better word. You make something. You give up expressing and start inventing.

From "Harry Mathews, The Art of Fiction No. 191," interview conducted by Susannah Hunnewell. Print version in The Paris Review No. 180 (Spring 2007).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)