Showing posts with label Sea. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Sea. Show all posts

Sunday, February 08, 2026

Monochrome

The city is behind me. In daylight, with no lights visible, the wind and the breakers cutting off all sound, one might think it uninhabited, but it isn't, it's just temporarily of no importance. The tall spires on its summit, rigid and precise, seem sketched by a draftsman's pencil with no concern for anything but the laws of geometry. Along the seawall a few sheets of newspaper take wing among scattered indifferent gulls, then fall, dispirited, huddling against unlit streetlamps and refuse cans.

Even where I stand, separated from the water's edge by a plateau of impenetrable rock a hundred yards across, I feel the cold mist against my face. The sun wanders out from cloud cover briefly, illuminating patches of wet stone scattered with fragmentary strands of seaweed, then loses heart and disappears. As the tide crests its bore surges into the mouth of the great river, annihilating its flow in a deafening battle of waters. Its accumulating force is terrible to contemplate.

There are no ships visible in the offing; if any there are, steaming their way miles out, they are hidden by waves and low clouds. The grand beacon, sunk into an exposed shelf of rock just up the coast, blinks metronomically, untended, unseen. I shudder and hoist up my overcoat, then turn my back on the sea and go home.

Monday, January 29, 2024

The Drifter

When I was growing up there was a commercial artist in our neighborhood named Gordon Johnson, whose specialty was paintings for advertising work and book illustration. He often worked from photographs that he had local people pose for, and this scene of the sighting of the Mary Celeste probably depicts people I knew, though at this point I'm no longer sure who they were. It was done, if I remember right, as part of a series for an insurance company. I have a print copy somewhere, but the image above was found online.

The Mary Celeste incident is one of the great nautical enigmas. An American merchant sailing ship is found in the Atlantic Ocean, a bit west of Portugal, with no ship's boat, a full cargo, a logbook a few weeks out of date, and no obvious evidence of fire, shipwreck, mutiny, or piracy. No trace of the crew or the passengers (which included the captain's wife and young daughter) is ever found. The ship is boarded by sailors from the Canadian brigantine Dei Gratia and brought to port in Gibraltar. After lengthy legal proceedings it is eventually reclaimed by its owners and put back into service. (Later proprietors sank it as part of an insurance scam, but that's another whole story.)

Various explanations and impostures have been put forth over the years, some of them fairly bizarre. An early one was offered, anonymously and fictionally, by a young Arthur Conan Doyle, who mistakenly called the ship the Marie Celeste (as many have done since) and imagined a tale of conspiracy involving a psychopathic ex-slave with a grudge against the white race and the missing ear of an African stone idol. Perhaps the most amusing solution was put forward by one J. L. Hornibrook:

I was aware of the story of the Mary Celeste from a fairly early age, though I never knew it in detail. This painting no doubt shaped how I imagined it. I've had a weakness for eerie nautical stories ever since.

The Mary Celeste incident is one of the great nautical enigmas. An American merchant sailing ship is found in the Atlantic Ocean, a bit west of Portugal, with no ship's boat, a full cargo, a logbook a few weeks out of date, and no obvious evidence of fire, shipwreck, mutiny, or piracy. No trace of the crew or the passengers (which included the captain's wife and young daughter) is ever found. The ship is boarded by sailors from the Canadian brigantine Dei Gratia and brought to port in Gibraltar. After lengthy legal proceedings it is eventually reclaimed by its owners and put back into service. (Later proprietors sank it as part of an insurance scam, but that's another whole story.)

Various explanations and impostures have been put forth over the years, some of them fairly bizarre. An early one was offered, anonymously and fictionally, by a young Arthur Conan Doyle, who mistakenly called the ship the Marie Celeste (as many have done since) and imagined a tale of conspiracy involving a psychopathic ex-slave with a grudge against the white race and the missing ear of an African stone idol. Perhaps the most amusing solution was put forward by one J. L. Hornibrook:

There is a man stationed at the wheel. He is alone on deck, all the others having gone below to their mid-day meal. Suddenly a huge octopus rises from the deep, and rearing one of its terrible arms aloft encircles the helmsman. His yells bring every soul on board rushing on deck. One by one they are caught by the waving, wriggling arms and swept overboard. Then, freighted with its living load, the monster slowly sinks into the deep again, leaving no traces of its attack.I thought about the incident during a trip to a library, when, while looking for something else, I spotted the title Mystery Ship stamped in gold on a green binding and opened it on a hunch. The book, written by a historian named George S. Bryan and published by Lippincott in 1942, was indeed about the Mary Celeste. I brought it home on a lark and found that it was actually quite good, though it's apparently long out-of-print and mostly forgotten except by nautical historians. Bryan looked carefully at the original documentary evidence (much of which he reproduces), went over the various explanatory theories point by point, reprinted a good portion of the Conan Doyle, and dispelled much of the nonsense that had accreted over the years. (The ship's cat was not dozing contentedly when the Mary Celeste was found, there were no live chickens on board, nor were there half-eaten meals still warm in the mess.) His own tentative conclusion was that the ship was deliberately abandoned because the captain had reason to believe that it was in grave danger, either from shipwreck or from an imminent explosion of its cargo (which consisted almost entirely of barrels of alcohol). The line that may have tethered the single ship's boat failed to hold, and the passengers and crew drifted into oblivion.

I was aware of the story of the Mary Celeste from a fairly early age, though I never knew it in detail. This painting no doubt shaped how I imagined it. I've had a weakness for eerie nautical stories ever since.

Labels:

Enigmas,

Mary Celeste,

Octopus,

Sea

Saturday, September 09, 2023

The Harbor of Lost Ships

Brad Fox, paraphrasing William Beebe's "final, disorganized notes on marine subjects," here describing the fate of shipwrecked sailors:

The sea angel Amphitrite swoops down for the sailors who have served her faithfully, and takes them to the court of King Neptune, who judges whether they've lived by the laws of the sea, whether they've been worthy.Update (September 2023): Not long after coming across the above passage, I picked up Sarah Orne Jewett's The Country of the Pointed Firs, one chapter of which recounts a tale of a voyage to the extreme north (somewhere above Labrador, or thereabouts) where sailors encounter a mysterious town populated by drifting "shapes of folks." The town, "a kind of waiting-place between this world an' the next," vanishes like mist when the sailors approach. Jewett's description is too long to quote here.

Others end up in a harbor in the far north where lost ships go. Some vessels crossing in the northern seas encounter these ghost ships, appearing and disappearing, flagless, unresponsive to salutations or threats. The Harbor of Lost Ships is locked in by high, barren, icy cliffs. In their shelter lie thousands of hulls, pressed together. Their ghostly crews walk the wharfs or stand still, as if they would sail off the next day, trimming sails and swabbing decks in the icy mist.

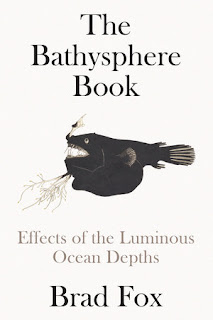

The Bathysphere Book: Effects of the Luminous Ocean Depths

Tuesday, September 13, 2022

Stateless person

The narrator of this novel by the elusive writer who called himself B. Traven is one Gerard Gales, an American seaman who oversleeps while in port and loses his identification papers when his ship sails without him. Unable to prove his identity, his nationality, or even his legal existence, he is deported from one European country to another until he finds a freighter whose captain has reason not to be fussy about documents. As it turns out, the aptly-named Yorikke, on which Gales becomes a stoker's assistant, is a dilapidated ship of fools, doomed to be scuttled for its insurance payoff. If the first part of the book is bureaucratic satire, lighter but also sharper than Kafka's in The Trial, the rest is largely taken up with harrowing descriptions of the working conditions of those who tend the boilers. Unlike the Kafka of Amerika, who never crossed the Atlantic at all, Traven clearly knew from first-hand experience what a stoker's existence was really like. But even at its grimmest the book never loses its dark sense of humor. The Yorikke, Gales assures us, is actually thousands of years old. Its apparent timelessness gives the tale yet another dimension.

Who was B. Traven? He usually claimed that, like Gerard Gales, he was an American whose documents had gotten lost. Sometimes he blamed the destruction of his birth record on the fires caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. He may have even believed it, and it may even have been true, although few scholars now give the idea much credence. That he was the same person as one Ret Marut, a German actor and radical writer whose paper trail went cold in the 1920s, is no longer seriously questioned, but then who was Ret Marut? We may never know with absolute certainty.

The Death Ship was originally published in German as Das Totenschiff. The earliest English-language edition, issued in 1934 by Chatto & Windus, was translated by Eric Sutton. It was followed almost immediately by an American edition brought out by Alfred A. Knopf, of which my Collier Books edition above is a reprint. No translator is indicated inside the book. Traven, who reportedly didn't like the Sutton version, chose to translate the novel himself for Knopf, expanding it as he did so. His command of English was faulty, however. The German scholar Karl S. Guthke explains what happened:

Traven, who would stubbornly maintain the fiction that his novels were originally written in English, allowed his German-language publisher, Büchergilde Gutenberg, to issue a new German "translation" in 1937 based on the Knopf version.

Who was B. Traven? He usually claimed that, like Gerard Gales, he was an American whose documents had gotten lost. Sometimes he blamed the destruction of his birth record on the fires caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. He may have even believed it, and it may even have been true, although few scholars now give the idea much credence. That he was the same person as one Ret Marut, a German actor and radical writer whose paper trail went cold in the 1920s, is no longer seriously questioned, but then who was Ret Marut? We may never know with absolute certainty.

The Death Ship was originally published in German as Das Totenschiff. The earliest English-language edition, issued in 1934 by Chatto & Windus, was translated by Eric Sutton. It was followed almost immediately by an American edition brought out by Alfred A. Knopf, of which my Collier Books edition above is a reprint. No translator is indicated inside the book. Traven, who reportedly didn't like the Sutton version, chose to translate the novel himself for Knopf, expanding it as he did so. His command of English was faulty, however. The German scholar Karl S. Guthke explains what happened:

The manuscript of The Death Ship that arrived in New York in 1933 was couched in an English that would have raised the eyebrows of most readers. As Knopf editor Bernard Smith reported, the text was so Germanic in vocabulary and syntax that it could never have made it in to print. And for good reason: Traven himself had translated the novel (as he was to translate the other novels Knopf would bring out), at the same time giving free rein to his lifelong passion for rewriting, cutting, and inserting new material. Knopf asked Traven to agree to a revision by Smith. Traven asked for sample pages and was favorably impressed. After instructing Knopf that only grammatical, syntactic, and orthographic changes were to be made, he authorized Smith to rework the entire manuscript. "This entailed treating about 25% of the text," Smith recalled. "In any given paragraph there was sure to be at least one impossibly Germanic sentence, and sometimes an entire paragraph had to be reconstructed." Smith stressed that his contribution in no way involved what could be considered literary or creative work on the three novels he revised. He had merely turned Traven's translations into acceptable English. It was clear to Smith from the beginning that English was not the translator's mother tongue; the syntactic thread was German, and even in Smith's reworked version the German original rears its head from time to time.The treatment of American place-names in the Traven-Smith version is a bit off. Referring to Wisconsin familiarly as "Sconsin" might just slip by unnoticed, but Chicago is casually referred to as "Chic," Cincinnati as "Cincin," and, least likely of all, Los Angeles as "Los." Other than that and a few eccentric colloquialisms the novel doesn't particularly "read like a translation" at all. Weirdly, it winds up being a work of American literature.

B. Traven: The Life Behind the Legends

Traven, who would stubbornly maintain the fiction that his novels were originally written in English, allowed his German-language publisher, Büchergilde Gutenberg, to issue a new German "translation" in 1937 based on the Knopf version.

Thursday, March 31, 2022

Night haul

The tackle creaks as the net is pulled in. On the lantern-lit deck the crew plant their feet and strain at the rope.

Spilled out on the boards, the finned and tentacled creatures blink and gape, but even as the men gather around them their irridescence fades and their jewel-like colors dim. Outlines blur. The seething multitude becomes still, then melts away into brine and breeze.

They cast the net out again and sail on, dragging the dead dark sea towards morning.

Labels:

Night pieces,

Sea

Sunday, February 13, 2022

A Stock of Curios

W. Jeffrey Bolster:

Able-bodied seamen versed in “the Mariner’s art” were admittedly a minority among black seamen; but men like Daniel Watson, who made five foreign voyages from Providence between 1803 and 1810, cultivated professional identities as seamen. As sailors, they wove together worldliness, skill, and class. Watson, and men such as the African-born David O’Kee, an ex-slave who made at least eight voyages from Providence during the 1830s, were fully socialized to the world of the ship, and probably more at home there than ashore. A blind sixty-year-old black Philadelphian introduced himself to the census marshall in 1850 as a “Seaman,” though his voyaging days were over. The pride black men felt in being identified as seamen is evident in the possessions left by Henry Robinson, a black laborer who died in Boston in 1849. Robinson owned the clothing, chairs, and stove that one would expect, but he also lived among a stock of curios that seem to have been collected at sea. Cases of “sea shells of several kinds,” “two coral baskets,” “one statue,” “one toy ship,” a series of pictures, and “two african swords and arrows” perpetuated images of a life considerably more exotic than the one that ended in a down-at-the heels Boston tenement house.

Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

The Curiosity Cabinet of Captain Nemo

In the eleventh chapter of Jules Verne's Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, the narrator, the noted natural historian Professor Pierre Aronnax, is given a guided tour of the Nautilus, the vast submarine skippered by his host (and captor), the mysterious Captain Nemo. One room is fitted out as a kind of museum, adorned with priceless works of art as well as wonders of the undersea world, the latter all hand-collected by Nemo. Aronnax's description of these treasures, as he recalls them later, includes a catalogue of molluscs worth quoting in full. I'll translate only the beginning, because most of the paragraph consists only of glorious French names that can be appreciated even for their purely formal qualities alone — and because many of the words aren't in my dictionary in any case.

Un conchyliologue un peu nerveux se serait pâmé certainement devant d'autres vitrines plus nombreuses où étaient classés les échantillons de l'embranchement des mollusques. Je vis là une collection d'une valeur inestimable, et que le temps me manquerait à décrire tout entière. Parmi ces produits, je citerai, pour mémoire seulement...(The last-mentioned specimen is doubtless the cone shell known in English as the Glory of the Seas.) The rest of the paragraph is a headlong rush of names, some recognizable, others (to me) inscrutable.

["A somewhat nervous conchologist would surely swoon before other, more numerous showcases where samples of the line of molluscs were arranged. I saw there a collection of immeasurable value, of which time does not permit a full description. Among these productions, I mention, solely from memory..."]

- l'élégant marteau royal de l'Océan indien dont les régulières taches blanches ressortaient vivement sur un fond rouge et brun, - un spondyle impérial, aux vives couleurs, tout hérissé d'épines, rare spécimen dans les muséums européens, et dont j'estimai la valeur à vingt mille francs, un marteau commun des mers de la Nouvelle-Hollande, qu'on se procure difficilement, - des buccardes exotiques du Sénégal, fragiles coquilles blanches à doubles valves, qu'un souffle eût dissipées comme une bulle de savon, - plusieurs variétés des arrosoirs de Java, sortes de tubes calcaires bordés de replis foliacés, et très disputés par les amateurs, - toute une série de troques, les uns jaune verdâtre, pêchés dans les mers d'Amérique, les autres d'un brun roux, amis des eaux de la Nouvelle-Hollande, ceux-ci, venus du golfe du Mexique, et remarquables par leur coquille imbriquée, ceux-là, des stellaires trouvés dans les mers australes, et enfin, le plus rare de tous, le magnifique éperon de la Nouvelle-Zélande ; - puis, d'admirables tellines sulfurées, de précieuses espèces de cythérées et de Vénus, le cadran treillissé des côtes de Tranquebar, le sabot marbré à nacre resplendissante, les perroquets verts des mers de Chine, le cône presque inconnu du genre Coenodulli, toutes les variétés de porcelaines qui servent de monnaie dans l'Inde et en Afrique, la «Gloire de la Mer», la plus précieuse coquille des Indes orientales;...

- enfin des littorines, des dauphinules, des turritelles des janthines, des ovules, des volutes, des olives, des mitres, des casques, des pourpres, des buccins, des harpes, des rochers, des tritons, des cérites, des fuseaux, des strombes, des pterocères, des patelles, des hyales, des cléodores, coquillages délicats et fragiles, que la science a baptisés de ses noms les plus charmants.The image at the top of page is by Adolphe Philippe Millot (1857-1921).

.

Below, with another catalogue of marine marvels, is the Louisiana singer-songwriter Zachary Richard, singing a song he co-wrote with his young grandson Émile (the very amusing lyrics can be found here).

Que la coque de ton bateau soit imperméable à l'eau

Quand tu te lances à la mer.

Monday, November 02, 2015

Spate

They emerged from the forest footsore, hungry, their panting dogs at their heels. Somewhere at their backs — a few hours, a day at most — their pursuers could take their time, knowing they would find them waiting where the river tumbled into the frigid sea. In any other season the shoreline was an arrow-shot further out, the water deep but untroubled enough to raft across. Not now; swollen by meltwater, the river churned, rising and falling, disgorging shards of ice and fallen trees — birch, larch — in a ceaseless roar. They stared into the torrent; its face bore the patient features of Death.

Brittle strands of rockweed skittered between their feet. In the offing, high above stray bergs, gulls dipped and soared in a wind so cold it struck the heart like a hammer. The mist lifted, but the sun failed to warm their bones. The bleached and broken skeleton of some great sea beast lay upended on the beach, as if welcoming them home.

Labels:

Sea

Saturday, August 01, 2009

The Woman on the Wharf

A number of years ago, before the harbor was dredged and deepened and the entire surrounding district modernized to accommodate container ships, an old man lived in a kind of cramped cabin or shack on one of the long wharves that used to jut out into the bay. He was employed as watchman and fire warden by an import-export firm that held a long-term lease on many of the harborside properties; in lieu of a salary he received free tenancy of the shack and daily meals and as much acrid coffee as he could drink in the firm's commissary. The work was undemanding -- walking the docks several times a night, keeping a lookout for suspicious activity -- and he found it preferable to life in a mission or the poor house. As he made his nightly circuit he carried a kind of staff or cudgel that he would, if necessary, wave in the air to persuade straying drunks to move on, as well as a switchblade in his pocket should real trouble arise, but the waterside was generally deserted once night fell, and it was no longer certain that much of value was passing through the wharves in any case.

Even in the fairest weather it was cold and misty by the water in the evenings, and the old man never left his lodgings without an ancient leather coat, a snug felt cap, and a pair of heavy work gloves. Though a series of pale electric lights had been strung overhead along the length of his route he carried a kerosene lantern with him at all times; his vision was beginning to fail and he held a particular loathing for the formidable rats that sometimes scuttled in front of him as he walked. He did not drink -- had never done so, even in all his travels in his younger days -- never mentioned family and had not been known to be ill or to request a day off. When he had occasion to engage in conversation, which was infrequently, it was noted that he spoke with a faint trace of an accent, though one that was hard to place. It was rumored that he might have been born in Norway or perhaps Orkney or the Hebrides, but no one knew for sure and no one ever took the trouble to inquire.

One particular October evening, after eating his supper in the half-deserted mess and catching a brief twilight nap in his cabin, the watchman dressed, collected his staff and lantern, and stepped out into the night air to begin his rounds. The moon was two nights past full, and its light was diffused by a thin, lingering mist. There were few ships moored at the docks that night, only a listing German freighter -- the Marut -- whose crew had made themselves scarce a few days before, as well as a pair of dark barges piled with scrap iron. Out on the water a long low coaler was steaming further up the harbor, guided by a pair of tugs, and its wake was rocking up against the moorings along shore. It sounded its horn, once, and the muffled echo repeated several times across the bay before dying out.

He passed beneath the dark belly of the freighter, listening to the slapping of the waves against its side, and began walking slowly out towards the end of the wharf. The slanted-roof warehouses that had been constructed along most of its length were now largely empty and stood in need of a coat of paint and more than a few fresh boards. Here and there a window had been broken and boarded up; the rest were dull with salt spray. Between the buildings lay collections of abandoned things: empty barrels and rusting coils of cable, a broken block-and-tackle and an old propeller.

As he approached the opening of the alley between the two outermost buildings he heard an unfamiliar sound that he thought for a second might have been a footfall. He was not alarmed; there was nothing out this far on the wharf to interest a prowler and he suspected it was really just the breaking of the surf, but almost immediately he heard it a second time -- it was unmistakable now -- and then once more again. It didn't sound like the solid tread of a booted workman -- more the light slap of a bare foot on wet wood -- and he wondered if a dog had gotten lost or had wandered out in search of a refuse pail to knock over for scraps. He turned and passed through the narrow alley, and just as he emerged and started for the end of the wharf he caught a fleeting glimpse of a slight figure, dressed in light-colored clothing, who was moving steadily ahead of him.

He called out, but the figure had already disappeared around the corner. He hastily adjusted his lantern, widening its pale glow, and followed, quickening his step. As he came to the end of the warehouse he saw that the fugitive had once again crossed to the opposite side of the wharf and was now heading outwards along the twenty yards of empty deck that remained at its tip. When he called again the figure turned, just for a moment, and to his considerable surprise he saw that it was a woman, whose long, light brown hair flowed down the back of a plain white dress that was not nearly warm enough for the season. In the instant before she turned her back to him again and resumed her course she gave him a frank stare unmarked by either fear or evident curiosity, and as she did so he observed that she was quite strikingly pretty but also not nearly as young as her stride would suggest -- a woman, to all appearances, well into her middle years.

He knew at once that there could be only one explanation for her presence at such an hour, and with more annoyance at her for trespassing on his domain than concern for her welfare he immediately resolved to frustrate her intent. He hurried forward -- not at a run, as the surface of the wharf was slick and treacherous, but as quickly as he could walk -- but she was moving swiftly herself and the distance was too great. When she reached the end of the wharf, just a few yards ahead of him, he nearly caught up with her and lunged for her arm, but it was too late. She did not jump into the bay but instead simply continued walking until the last metal girder was no longer beneath her feet and she plunged downwards and out of sight, making a hollow sound as she broke the surface. The watchman held his lantern up and looked out. A few yards out, the woman had begun to swim calmly and purposefully into the bay; he ordered her to return but she either didn't hear or chose not to heed. He hesitated; there was a dinghy hauled up at the shore end of the wharf but he knew that the oars were locked in a shed and he would have had to find the key. Deciding there was no time, he set the lantern down on the end of the wharf, hurriedly shed his coat and cap, then unbuckled and drew off his boots. Before he leapt he yelled as loud as he could for help, knowing there was little chance that anyone would be within earshot.

As he hit the water the shock of the cold convulsed him and it was a moment before he could regain control of his limbs. Treading water until he had caught his breath, he drew a bead on the woman, illuminated by the moonlight now some thirty yards offshore, and began his pursuit.

He was an experienced swimmer, though no longer as strong as he had once been, and though he quickly drew up to within a few yards of the woman he could not overtake her. Even as he was appalled by her recklessness he could not help but marvel at her practiced stroke. He had never known a woman to swim so well, certainly not in the cold and powerful currents of the bay. She looked over her shoulder briefly and caught sight of him, but gave no indication that his presence affected her or would alter her plan. There were lights on the far shore and on the boats pulled up alongside, casting shining trails across the water, but they were too far away for anyone there to be able make out the two swimmers, even had someone chanced to look, and at that distance the chopping of the waves would muffle even the loudest cry for help. There was nothing for it but to follow the woman until she began to tire, and then hope to persuade her to return with him to shore, assuming his own strength did not give out first.

As she reached the midpoint between the near and far shore, where the channel was cut the deepest, she began to change her course, swinging around until she was parallel to the current, bearing outwards towards the mouth of the bay. For a moment he persuaded himself, with relief, that she was about to make a full circle and return to the wharf and that her madness had, after all, some limit, but all too soon it was clear that that was not at all her purpose. She kept to the center of the bay and even seemed to redouble her pace. He felt fury rising in him at her perverseness and obstinacy, but fascination as well, as he wondered about the mettle of a woman whose strength and determination were more than a match for his own.

They continued swimming and soon had left the busiest part of the harbor behind. The surface of the water was darker here, lit only by the haze-shrouded moon, and the waves began to pick up and slap around him and into his face, but still he maintained a fixed eye on the woman ahead. He could not fathom what purpose she might have in acting as she did; if it were to drown herself she could have done so simply and far closer to shore, unless perhaps his unexpected interference had spoiled her design.

By now, he was no longer swimming to save her -- at this point he no longer thought he could -- nor even to save himself, but still he followed her without knowing why, as if, having already pursued her so far, he had surrendered his will and forfeited the right to turn back. Curiously, he felt no fear. As the cold penetrated his muscles his limbs began to tire and the water felt heavier and darker around him. The steady pull of the falling tide was taking hold, drawing him out into the widest part of the bay. He had begun to swim more slowly now; she seemed to sense this and relaxed her pace as well, turning her head every few strokes as if to gauge where he was. He called to her and for once he thought he saw her listen and consider his words, but still she swam outward, outward...

At last he was exhausted and could do nothing but float. As the current bore him along the woman swam in time with it, still showing no sign of feeling either cold or fatigue. The waves began to break over his head and he gasped for breath, unable to move. The figure ahead of him stopped swimming and turned towards him one last time, treading water, observing him silently, intently, without emotion. As he felt himself being drawn down into the dense, deep water her face was the last thing he saw.

Two days later the crew of a fishing boat spied the watchman's body drifting a few yards offshore at the outermost point of the bay. They notified the harbor patrol, who gaffed him out of the water and brought him to the city morgue. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

Sunday, June 14, 2009

Along the bay

She is, he thinks, as beautiful a girl as he has ever seen. She is studying the cello and he -- without great conviction -- environmental science, but even before they become friends he spies her one day making her way across campus, in subdued but easy conversation with a friend, her long hair loose and falling midway down her back. At first she reminds him, he thinks, of a painting he remembers seeing somewhere, a Rossetti or something like that, but when he gets a closer look he sees that he is mistaken. There is nothing remote or iconic about her face; her features are delicate, her expression open and unaffected. Eventually they meet and become friends but nothing more. He has a steady girlfriend through most of his junior and senior years and she, he believes, has a boyfriend who goes to some other school.

After college they lose touch, but by chance a year later they each spend the summer months in a resort town on the coast. When he runs into her unexpectedly, just as the tourist season is starting to hit, he is waiting on tables in a seafood place on the docks and renting a room by himself in a rickety backstreet walkup, his future plans unknown. She is living by herself in a tiny cottage on the bluffs outside of town, rehearsing for a festival with a local chamber orchestra and preparing to begin her MFA. He calls her up and stops by for dinner one evening and with what seems to him almost miraculously mutual avidity they wind up in bed together. Within a week he has moved in, carrying the few essential possessions he hasn't stowed at his mother's house or his father's place back home: a backpack with an aluminum frame, a sleeping bag, a sackful of CDs, and an outback hat.

On warm evenings, while she waits for him, she moves a chair onto the porch and plays to the distant bay, watching the shadows of the walnut tree that overhangs the building quiver and drift across the floor planks. Then he comes home with fish and chips and a bottle of wine purloined from the kitchen; he is tired but his eyes brighten when he sees her face. She lights a pair of candles and sets them on a table by the picture window. While they eat he tells her stories of his day to make her laugh, and before long they are once again entwined.

Late at night, when the embers of their desire are at last consumed, he likes to lie back in the dark with his eyes open and imagine his future with her, and she curls silently beside him and thinks about how to tell him that he has none.

Labels:

Sea

Monday, May 11, 2009

The sea

The boats are returning to the harbor now, one by one, the reflection of their torches flaring across the water in the last moments of twilight. Tired and grim-faced -- it's been a bad day's haul, it seems -- the fisherman will pull along the docks, tie up, and silently unload their catch. From where I stand, along the rocks where the jetty meets the long, grey beach, I can't see their faces, but I know each one of them by name, I know their thoughts, I know their wives, and I teach most of their children.

The policemen have completed their enquiries and have left town. They haven't said as much, but I know they won't be back. They will file their report -- missing person, no evidence foul play -- the folder will be neatly tucked into a cabinet in the district office, and no one will ever look at it again. It's always the same. As far as the authorities are concerned, keeping track of the activities of the living is responsibility enough; expecting them to bother with the affairs of those who have disappeared without trace would be asking too much, and in the end what good would it do, anyway?

My mother was the first person in the long history of this village to be able to read and write, and had she not given birth to me she could very easily have been the last. She wasn't from here, naturally. Her birthplace was twelve miles inland, in a real town with lamps and cast-iron fences, newspapers and brightly lit cafés. When she was nineteen, having already lost both parents, she came here with some friends on a lark and, as the result of a series of circumstances the nature of which I was never allowed by my mother to have more than the vaguest knowledge, never left. It would be appealing to be able to say that she stayed because she fell in love with the village or with my father, but I'm not sure that either was ever true. Be that as it may she remained all the same, and in time I was born.

My mother was never able to teach my father to do anything more than write his name -- a skill I'm quite certain he never employed when he was out of her sight -- but she saw to it, in spite of our poverty, that I was supplied with books, paper, and writing implements, and she pointedly neglected my instruction in the tasks that in the village are customarily allotted to girls, namely gathering seaweed and shellfish, tending to the gardens, and looking after infants, one's own or those of other people. My mother put on no airs about her own original station in life nor did she entertain any illusions about how far she had descended from that condition in consenting to marry my father, but she regarded herself as a civilized women and civilized women did not muck about in tide pools and lazy beds. My mother performed her obligatory household duties, the unending cycles of cooking, cleaning, and laundering, without complaint, but she never suggested to me that these activities were sufficient to constitute one's mission in life. Since it seemed unlikely that I would ever leave here or find a suitable husband, her fixed intention was that I become the village's teacher and instruct the children in the rudiments of literacy, arithmetic, and religion. Had it not been for the burden of attending to me and my father, a burden that increased after my father's health began to fail, she might well have taken up the task herself. As it was, by the time my father went to his grave her own health had begun prematurely to decline. I was already sixteen and therefore, in my mother's judgment, sufficiently prepared to see to the village's education. She persuaded her neighbors -- with what kind of arm twisting I will never know -- to entrust their offspring to my tutelage in exchange for a few coins a week, enough to pay for a few supplies and my own very modest requirements for food, firewood, and other necessities. I have never harbored any illusions about the lasting effect I have had on my charges, but at the very least I know that they will not be as ignorant as their parents.

There were two policemen this time. The older one, the one who seemed to be in charge, seemed familiar, though he didn't appear to remember me. They always come around to me eventually. The villagers are a close-lipped lot, and even when they do decide to let on a bit their ramblings don't appear to make much sense, at least to outsiders. I, on the other hand, know everyone in this village, I understand their ways, and I'm happy to tell the policemen whatever it is they want to know. The missing man lived in a cabin along the harbor; he lived alone; he drank no more than anyone else; he had no enemies one night that might not be his friends again the next. And so on. They enquire, as discreetly and indirectly as they can, about his relations with women; I tell them plainly what I know or may have heard.

In the end I really haven't told them very much at all, but it's all they need or want to hear. What they don't want to hear is what no one has told them but what everyone in the village knows: that no trace of the man will be found, that no witness to his fatal last moments will come forward, that no bloody footprints will be found leading into the brush.

For the most part, the people who live in this village die in one of three ways: by drowning, by drinking, or at the point of a knife. Little given to reflection or sentiment, they fear none of the three. What they do fear has no name -- for how can you name something that no one has ever seen? -- and if the police have gotten wind of it, one way or another, as they make their way around the village, through some slip of the tongue or muttered aside, they lift their pencils from their notebooks and pretend they haven't heard. Only later, perhaps at the very end of their interview with me, as they stand awkwardly before the door, their questions concluded but still held back as if by magnetic force, will they allude to what people are hinting but what of course is nothing but ignorant nonsense and superstition, that the disappeared man has been taken by something silent and unseen, something that visits the shore only after long intervals and only on the blackest, coldest, mistiest nights, something that lifts latches and subdues without sound and that leaves no evidence of a struggle behind. And I'll tell them that yes, that's what the people think, and that's what they have always believed, and if they ask me if I believe it I'll tell them that what I believe or don't believe doesn't matter. And the younger policeman might suggest that couldn't it be true that the vanished man might simply have succumbed to madness and alcohol, that he might have lost his mind in the depths of night and strode out into the sea and drowned, and I will tell them that yes he might well have but that they can scour the shoreline from now until doomsday and nobody will ever find his body.

Monday, April 13, 2009

The rower

One warm August night, unable to remain asleep, I rose, dressed, and went outside, hoping that a walk by the water's edge would help calm my thoughts. I set out along the gravel path that leads to the bay, my footfalls crunching on its pebbled surface, guided forward by moonlight and memory. Not until I had passed the last house did I begin to hear the faint lapping of wavelets on the rocks along the shore. Ahead of me, across the water, stretched the long, low peninsula on the other side of the bay; if anyone out there was, like me, stirring at that hour, their lights were too distant and too dim to be seen from where I stood. There were lobster boats moored here and there alongshore, bobbing in the waves as if rocking in their cradles, but the only sign of maritime activity in the offing was far out, beyond the limits of the bay, where one or two large vessels, with drafts too deep for our little harbor, were churning through the open sea, parallel to the coast, bound for Boston or Halifax.

I turned onto the narrow footpath that runs along the shore and headed away from town, keeping my chin down and my eyes on the path's uneven surface, which is broken in places by gullies, washouts, and exposed roots. The tide was high but had crested and begun to ebb away again out of the bay; only a few yards of boulders and patches of coarse sand lay between the path and the water. The wind off the bay was not particularly brisk, but even so it bore a pleasing and welcome chill, though I was not sorry to have picked up my windbreaker before I left the house. On the inland side, as I walked, I passed a succession of wealthy summer homes with long, carefully tended lawns, some of them terminating in low masonry walls adorned with electric lanterns. Though here and there a floodlight shone down on the path the houses were silent, the occupants either asleep or perhaps reading or drinking quietly in solitary inner rooms. After a mile or so the houses gave way, first to a thicket of beach rose and sumac, then beyond that to aspen and stunted white pine, the overgrowth of what had once been burned over in a great fire many years before. The path climbed away from the shore, which briefly disappeared from view, before descending again to skirt a narrow horseshoe of stony beach that was rarely discovered by visitors, even during the height of the season when it seemed that the whole area swarmed with hikers and weekenders.

It was when I had made my way around and was approaching the far limit of the cove that my eye caught something moving in the water, thirty yards or so offshore. It was low in profile and partly hidden by the waves, and at first I thought it might be either a log or a surfacing dolphin, an animal not uncommon in these waters in the summer months. I stood still and watched the shape as it glided through the reflected pallor of the moon, and only after a moment or two had gone by could I identify it as a kind of lifeboat or dinghy, in which a solitary pilot, seated at the middle bench, could be seen steadily rowing with the outgoing current. The craft bore no lantern nor any sign of cargo or tackle, and the silent figure working the oars, dressed in a gray cloak with the hood down, appeared, from its long hair and slightness of build, to be a woman. Her head was bent down from the exertion and her face was turned away from the shore; she rowed as if she had some familiarity with the task but not powerfully, pacing herself, being evidently in no hurry to get where she was going.

I continued along the shore path, matching my advance to the progress of the boat. Beyond the cove the bay widens, but the rower maintained her distance from the shore and did not venture out into the deeper channel. The wind was beginning to pick up and I zipped my windbreaker, but kept my hands out of my pockets to assist my balance on the stony path. Once or twice I stumbled and knocked loose a stone, but the sound that echoed as it struck onto the cobbles below either failed to reach the boat or did not concern its occupant. She rowed on at the same fixed pace, occasionally casting the briefest half glance over her shoulder to hold her course. I began to wonder where she could be heading at that hour. There were no docks or houses to the end of the point, and if she had been so reckless as to go boating alone, for recreation, at night, it seemed high time for her to reverse her heading and make for the shelter of the town. Up ahead, at the end of the point, barely discernible in the darkness, lay the long thin breakwater that sheltered the bay from the heavy surges and swells of the ocean. For an unaccompanied boatman -- or boatwoman -- to venture into those waters at night in such a craft, even in favorable weather, would be an act of almost suicidal folly.

The path shook off the last patches of woods and scrub and descended directly to the water's edge; at the same time it became rockier and more irregular. I clambered ahead as fast as I could manage, clearly visible now on the shore if the woman were to turn, but still she kept her head averted, tucked into her far shoulder. She began to gain ground on me; her way was smoother and she was gaining momentum as the tide drew her along. I stumbled, turned my ankle slightly, and scraped my hand on a rock, then I righted myself, rubbed off the sting in my palm, and hurried forward. She was nearing the breakwater now and beginning to veer away from the shore. I hoped that she was about to turn and circle back, but instead she rowed steadily onward, shooting towards the churning gap.

I stepped onto the breakwater and leaped along its skeleton of immense stones, keeping an eye on the boat as our courses swiftly converged. In seconds I was almost at the jetty's end, and the woman, as she hurtled forward, was now no more than ten yards away. At last I saw that there was no doubting her course, nor hope of stopping her, and in desperation I shouted to her, and at that moment, for the first time, she heard me and turned her face -- or should I say, what remained of her face --in my direction.

Below the thin and tangled filaments of her hair the woman's eyes were so deeply sunken they might well have been hollow sockets. Her nose was eaten away entirely, and all that remained of her lower jaw was a jagged shard of bone and a few exposed and broken teeth. As the craft shot through the gap into the ocean she fixed her gaze on me, but her expressionless face did not once move or twitch and no sound issued from that grotesque maw. Her hands and arms kept to the rhythm of their rowing; I turned my body and met her gaze, watched her recede into the distance, until she suddenly snapped her head down and away from me once more, vanished into a swell, re-emerged, vanished again, and was almost instantly swallowed by darkness.

I did not want to consider what errand might have brought the silent rower into town, whether she had visited some inconceivable lover there or was perhaps searching vainly for a lost paramour or child who had been dead for generations. I stood on the end of the breakwater for some time, trembling and unable to move, petrified that I might lose consciousness and topple into the water and be drowned and battered against the rocks. When I had sufficiently gathered my composure I began gingerly to retrace my steps, buffeted by the wind and the salt spray, until once again I was standing alone on the shore at the end of the point. I fell to my knees for an instant, feeling tears of horror and anguish well up in my eyes, then I collected myself, shook off the chill, and began to make my way back to town.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)