Monday, July 22, 2019

Notes Against a Manifesto

What is to be done? Is there anything more exasperating than the cycle of analysis regarding our political situation? How did we get here? Whose fault is it? The implicit argument too often seems to be that there is no dilemma, no reason to trade off one thing for another and not have it both ways, as long as you listen to me. I'm neither a prophet nor a political scientist — and no one listens to me (nor would I expect them to) — but at a fundamental level all of this profound wisdom seems to me to miss the point.

The manipulation, the lies, the social and economic and cultural anxieties, to which we all have been subjected are amply documented, and all of it takes its toll, warps our understanding and our better natures, makes us putty in the hands of demagogues. Tout comprendre, c'est tout pardonner, wrote Tolstoi, and that is true for the novelist but not satisfactory to the moral philosopher. If we're nothing more than the sum of our influences — and perhaps we're not, we can't prove the contrary — then we're not moral agents at all.

The social sciences are concerned with the study of causes; literature (of the best kind, something I insist on the existence of, Literature-with-a-capital L) is about freedom. Not freedom as the absence of chains or bars (not all of us have that luxury), but freedom as the consciousness of the ability to be a moral agent, in whatever sphere, even in the most constrained of circumstances.

Stalin supposedly commanded writers to be "engineers of human souls," but no writer worthy of the name is capable of doing any such thing. (Milan Kundera, among others, has said all of this better in his writings on the novel.) Engineers of the soul are, in any case, a dime a dozen. Nevertheless, writers can, and do, interrogate the world, and no sphere can be barred to them, politics least of all. Writers have (or don't have) responsibility because we all do (or don't).

The symbol of moral freedom is not, in my view, the broken chain but the absence of a net, the high-wire act with nothing to fall back on. A single false step will be relentlessly exposed. Anything else, all the deadly sins, can, in time, perhaps be forgiven, but not bad faith.

For the pious of various stripes there is rarely any dilemma; their convictions will always protect them from the pitfalls of freedom. But such security is itself highly contingent, for if the net that protects them is whisked away where are they then? (The argument that the net must necessarily exist because we need it is pure sleight-of-hand.) Some, it is true, manage to maintain something that amounts to faith without believing there is a net beneath them, and with them I have no quarrel. I'm not really interested in how people get to virtuous action, or what flags they wrap themselves in to justify its opposite. But at some point you need to be able to look in the mirror and recognize what you see.

In the end the overriding issue at the moment is comfortingly binary: Fascism, yes or no?

Tuesday, July 16, 2019

Ouch (2)

Jeopardy clue: "Inscribed on Woody Guthrie's guitar: 'This machine kills' these." Contestant's response: "What is 'trees'?"

(Correct question: "What is 'fascists'?" Kudos to Jeopardy for remembering, especially now.)

Labels:

Amusements,

Jeopardy

Sunday, July 07, 2019

In Kakania

Robert Musil:

The administration of this country was carried out in an enlightened, hardly perceptible manner, with a cautious clipping of all sharp points, by the best bureaucracy in Europe, which could be accused of only one defect: it could not help regarding genius and enterprise of genius in private persons, unless privileged by high birth or State appointment, as ostentation, indeed presumption. But who would want unqualified persons putting their oar in, anyway? And besides, in Kakania it was only that a genius was always regarded as a lout, but never, as sometimes happened elsewhere, that a mere lout was regarded as a genius.The Man without Qualities (Wilkins-Kaiser translation). "Kakania" was Musil's coinage for the kaiserlich und königlich Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Labels:

Robert Musil

Saturday, July 06, 2019

Lucas, His Long Marches

Julio Cortázar:

Everybody knows that the Earth is separated from other heavenly bodies by a variable number of light-years. What few know (in reality, only I) is that Margarita is separated from me by a considerable number of snail years.Translated by Gregory Rabassa. Lucas, the narrator, is a kind of alter ego of the author. The above piece is the final chapter of the book (which has been out of print for many years).

At first I thought it was a matter of tortoise years, but I've had to abandon that unit of measurement as too flattering. Little as a tortoise may travel, I would have ended up reaching Margarita, but, on the other hand, Osvaldo, my favorite snail, doesn't leave me the slightest hope. Who knows when he started the march that was imperceptibly taking him farther away from my left shoe, even though I had oriented him with extreme precision in the direction that would lead him to Margarita. Full of fresh lettuce, care, and lovingly attended, his first advance was promising, and I said to myself hopefully that before the patio pine passed beyond the height of the roof, Osvaldo's silver-plated horns would enter Margarita's field of vision to bring her my friendly message; in the meantime, from here I could be happy imagining her joy on seeing him arrive, the waving of her braids and arms.

All light years may be equal, but not so snail years, and Osvaldo has ceased to merit my trust. It isn't that he's stopped, since it's possible for me to verify by his silvery trail that he's continuing his march and that he's maintaining the right direction, although this presupposes his going up and down countless walls or passing completely through a noodle factory. But it's been more difficult for me to check that meritorious exactness, and twice I've been stopped by furious watchmen to whom I've had to tell the worst lies since the truth would have brought me a rain of whacks. The sad part is that Margarita, sitting in a pink velvet easy chair, is waiting for me on the other side of the city. If instead of Osvaldo I had made use of light years, we probably would already have had grandchildren; but when one loves long and softly, when one wants to come to the end of a drawn-out wait, it's logical that snail years should be chosen. It's so hard, after all, to decide on what the advantages and the disadvantages of these options are.

Thursday, July 04, 2019

The Age of Ubu

"A painting by Jean-Martin Bontoux of King Ubu in Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi, late twentieth century," via The New York Review of Books. The image accompanied an article by Charles Simic, who wrote in part:

One only had to watch the confirmation hearings for Trump's cabinet to fully grasp the sort of men and women who are now in charge in all spheres of life in this country. Lacking any feeling of empathy for their fellow Americans and their problems, convinced in their minds of their superiority because of their immense wealth, eager to pillage this country even more, they are bound to do evil because that's the kind of people they are. In the meantime, the crimes and injustices that are bound to multiply in the months and years ahead is what we have to look forward to. Ubu Roi may not be a great play, but we don't deserve Shakespeare."Year One: Our President Ubu"

Two years on, the situation has only grown more grotesque.

Labels:

Alfred Jarry,

Politics

Sunday, June 30, 2019

Lèse-majesté?

"Cartoonist loses job after image depicting Trump ignoring dead migrants to play golf" (The Independent).

Image by Michael de Adder.

Monday, June 24, 2019

Notes from a Commonplace Book (25)

Quoted entirely out of context:

Being in a strange land and among strange men and things, meeting with customs and surrounded by circumstances widely different from all their previous experience, ignorant of the precise state of affairs here, and wanting education and flexibility by which they could adapt themselves to their new and unwonted position, they necessarily form many impracticable purposes, and endeavor to accomplish them by unfitting means. Of course disappointment frequently follows their plans. Their lives are filled with doubt, and harrowing anxiety troubles them, and they are involved in frequent mental, and probably physical, suffering.Report on Insanity and Idiocy in Massachusetts, by the Commission on Lunacy, Under Resolve of the Legislature of 1854.

Labels:

Migrations

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Curiosity Cabinet

This entertaining popular account of the Victorian mania for natural history was published by Jonathan Cape and Doubleday in 1980, and has apparently been out of print for decades, perhaps because its color plates would have made it too expensive to reprint. That's unfortunate, because Lynn Barber (on whom more below) did a first-rate job of researching, organizing, and writing the book, and has many interesting things to say both about natural history as a popular Victorian pastime and about weighty scientific figures like Owen, Agassiz, Philip Gosse, and Darwin, not to mention the likes of Frank Buckland, who seemingly ate everything he studied. I read it not too long after it appeared and have occasionally revisited it. Many fine books on the history of 19th-century natural science have appeared before and since but I suspect that few are as entertaining. Barber has a solid command of the major scientific advances and controversies, but she also has a sharp wit and a knack for a good anecdote.

The diary of Caroline Owen, wife of the zoologist Richard Owen, records an odd incident when she was visited by a lady who produced out of her reticule 'a thing which she had been told was an unborn kangaroo.' She (the lady visitor) had brought it to show Richard Owen, but 'she was hesitating about bringing such an "indelicate" subject to a gentleman.' Caroline set her fears at rest by assuring her that the kangaroo had not only been born but had lived for some time, and they then settled down to tea and chat, since Richard was not at home anyway, but it is surely strange that a woman who had no qualms about carrying a dead kangaroo around with her would then start blushing and trembling at the thought of showing it to a gentleman. It reminds us, if we need any reminder, that Victorian delicacy had very little to do with natural modesty and a great deal to do with cultivated prurience.Of Buckland's gustatorial experiments there is much to report, including:

While at Oxford, he feasted on panther, sent down from the Surrey Zoological Gardens. 'It had, however, been buried a couple of days,' he noted, 'but I got them to dig it up and send me some. It was not very good.'And here is Barber on science versus religion in the days before Darwin upset the apple cart:

When we talk about the 'clash' between religion and science in the Victorian era, we are talking about the 'clash' between an articulated lorry and a grain of sand. Science counted for absolutely nothing compared to religion. It stood, at best, in the relation of a handmaid to religion but, like a handmaid, it could be sacked if it ever showed signs of being uppity.The jacket flap of the book identifies Lynn Barber as "a British journalist educated at Oxford," and notes that "she is currently working on a new book focusing on another aspect of Victorian popular culture." (Unmentioned in the author bio is the fact that her journalism had included seven years at Penthouse.) As far as I can tell, she never published the "new book" alluded to, but she didn't disappear into obscurity either. She has had a long career as a writer and interviewer for various publications (she has been called "the rottweiler of Fleet Street"), and has published a memoir recounting her affair, while in her teens, with a dashingly charming older man who turned out to be not only involved in various criminal activities but married to boot. That account, An Education was made into a likeable 2009 film starring Carey Mulligan, which I saw several times before I realized that she and the author of The Heyday of Natural History were one and the same. As to her curious career path and Heyday's place in it, Barber has this to say:

There are whole subjects I used to know that I have since forgotten. I have a certificate that says I can do shorthand at 100 wpm – how did I acquire that? Did I bribe the examiner? I got top marks in A-level Latin – eheu fugaces, I can't translate a line of Horace now. In my brief, improbable career as a sex expert, I wrote a manual called How to Improve Your Man in Bed that was accepted at the time as an authoritative guide. How did I have the chutzpah to do it? I also spent five years researching and writing a book, The Heyday of Natural History, which involved reading all the popular natural history books of the Victorian era. Gone, all gone. I seem to have an auto-erase button in my brain that says that once I have 'done' a subject, I no longer need retain it.Luckily, talent is the one thing she has apparently never been short on.

Sunday, June 16, 2019

Stephen O. Saxe (1930-2019)

The printing historian Stephen O. Saxe died on April 27th of this year, according to a memorial notice in the New York Times today (June 16th) and a brief note from the American Printing History Association, of which he was a founder. Saxe followed an interesting career path that led him from Yale Drama School to television set design to book design at Harcourt, Brace, but it was for his activities as an amateur (in the best etymological sense of the word) that he is best known, at least among printing scholars and enthusiasts. Among his publications was the book pictured above, the definitive study of the 19th-century iron presses that were the first major revolution in printing technology after Gutenberg. (Appropriately, the book was first published in a letterpress edition by Yellow Barn Press, though a trade edition followed.)

I met Stephen Saxe once. I had written to him with a couple of questions about some research I was doing and he generously invited me — a stranger and total novice to the field — and a printmaking friend to his home in White Plains, where he spent a couple of hours showing us his printing equipment and some treasures from his library, including an extraordinary 19th-century French specimen book filled with elaborate typographical decorations. (The APHA announcement has a nice photo of Saxe at his home.) There aren't many of his kind still around.

Update: Amelia Hugill-Fontanel has written a longer appreciation for the APHA website: "Stephen O. Saxe, A Partner in Printing History, (1930–2019)."

Labels:

Letterpress,

Printing

Monday, June 10, 2019

Mistaken Identity

An incident that Julio Cortázar (a noted admirer of Verne) would no doubt have appreciated, as related by Alejandro Zambla:

I remember how at sixteen, I convinced my dad to give me the six thousand pesos that Hopscotch cost, explaining that the book was "several books, but two in particular,"* so that buying it was like buying two novels for three thousand pesos each, or even four books for fifteen hundred pesos each. I also remember the employee at the Ateneo bookshop who, when I was looking for Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, explained to me patiently, over and over, that the book was called Around the World in Eighty Days and that the author was Jules Verne, not Julio Cortázar."Bring Back Cortázar," from The Paris Review (online) October 17, 2018.

I can sympathize, though, with the poor bookseller, who was no doubt used to dealing with cronopios like this fellow (played by Marty Feldman):

* The phrase is borrowed from the "Table of Instructions" of Hopscotch.

Sunday, June 02, 2019

Monday, May 13, 2019

"Mala Cosa" (Cabeza de Vaca)

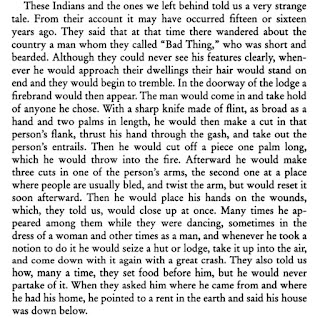

The Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca recounts an incident that was related to him by Native Americans he encountered during his long sojourn across the southern US and northern Mexico:

Narrative of the Narváez Expedition, edited by Harold Augenbraum.

Cabeza de Vaca was one of a handful of survivors of a 16th-century expedition to Florida that went catastrophically wrong. The accuracy of his account of his travels on many points has been questioned, but few things in it are as difficult to believe as the one thing that is unquestionably true, which is that he and three other men did survive eight years wandering among various Native American peoples before finally meeting up with a group of his countrymen near Culiacán in Sinaloa. Along the way he found himself cast in the role of faith healer, and claimed to have performed countless miracles on ailing (and very grateful) Indians.

The passage above has been much pondered. It appears to record some kind of shamanic performance reminiscent in some ways of modern "psychic surgery" cons and fortune-telling bujo scams. How the Indians understood what they told Cabeza de Vaca, and how it differed from what he recorded, is impossible to say. It's the oddest passage in the book.

Labels:

Cabeza de Vaca,

Enigmas,

Mexico,

Notes

Ouch

Jeopardy clue: "John & Priscilla Alden lie in the U.S.A.'s oldest maintained cemetery, which like a poem about the couple, is named for this person." Contestants' proposed questions: "Who is Poe?," "Who is Arlington?," and "Who is Mary?"

(The correct question: "Who is Myles Standish?")

Labels:

Amusements,

Jeopardy

Sunday, May 12, 2019

On Ants (Thomas Bewick)

"The history and œconomy of these vary curious Insects are (I think) not well known — they appear to manage all their Affairs, with as much forethought & greater industry than Mankind — but to what degree their reasoning & instructive powers extend is yet a mystery — After they have spent a certain time toiling on earth, they then change this abode, get Wings, & soar aloft into the atmosphere — It is not well known what state they undergo, before they assume this new character, nor what becomes of them after."

(Memoirs)

On Being Alone

"As the lodges afforded so little shelter, people began to die, and five Christians quartered on the coast were driven to such extremity that they ate each other until but one remained, who, being left alone, had nobody to eat him." — Cabeza de Vaca

Adapted from the Lakeside Press edition of Narrative of the Narváez Expedition, edited by Harold Augenbraum.

Labels:

Cabeza de Vaca,

Notes

Friday, May 03, 2019

An Existential Necessity (Luc Sante)

The Paris Review has inaugurated a new blog, Pinakothek. Written by Luc Sante, it's devoted to "miscellaneous visual strata of the past." Here's an excerpt from the second post, "Arcade":

Getting yourself photographed was a pastime and an existential necessity. It reminded you that you existed outside your own head. It showed you your face as others would see it. It gave you an opportunity to compose yourself, although few had the skill to do so successfully, and often the photographer’s haste and hard sell would mitigate against it. Most people come off in arcade pictures as if they had suddenly been shoved onstage to face an audience of thousands."Pinakothek" (from a Greek and Latin word for a picture gallery) was also the title of a short-lived feature that Sante maintained on his website a number of years ago.

Labels:

Luc Sante,

Photography

Wednesday, May 01, 2019

Hera

Her sons are out of college and living lives of their own by the time her husband leaves. She could stay on in the house but every room has bad memories, so she winds things up and moves back to the river town where she was born. It's the same river but the people have moved on. Old acquaintances, when she happens to bump into someone she recognizes, are pleasant enough but their faces are burdened with histories she no longer shares. Downtown there are newcomers, refugees from a faraway war that has disappeared from the headlines. She rather likes the women, who are friendly, direct, and tough, but finds the men a harder read. She volunteers a bit and joins a gym, and keeps the few grey-haired men who seem to sense an opportunity at arm's length.

On overcast days she likes to walk through town and over the bridge and watch fishermen drop their lines into the dark water. Sometimes the drawbridge rises and a barge goes by, its wake slowly rippling until it breaks on the shore. She wonders what the barges carry and where they are bound, upriver empty and downriver full. Semis cross the bridge and sometimes sound their horns at her; she thinks they wouldn't bother if they could see the lines in her face.

The mail brings letters, catalogs, bills. She keeps her rooms tidy, cooks casseroles that last for days, reads into the night, rises with the dawn. Sometimes she sees great flocks high above and hears the faint cries of birds returning to Canada for the summer. She resolves to make the same trip some spring, when the moment is ripe and the last ice floes have broken up.

Labels:

Migrations

Monday, April 08, 2019

Notes for a Commonplace Book (24): Temporary Separateness

Alice Munro:

This lucky woman, Joan, with her job and her lover and her striking looks—more remarked upon now than ever before in her life (she is as thin as she was at fourteen and has a wing, a foxtail of silver white in her very short hair)—is aware of a new danger, a threat she could not have imagined when she was younger. She couldn't have imagined it even if somebody had described it to her. And it's hard to describe. The threat is of change, but it's not the sort of change one has been warned about. It's just this—that suddenly, without warning, Joan is apt to think: Rubble. Rubble. You can look down a street, and you can see the shadows, the light, the brick walls, the truck parked under a tree, the dog lying on the sidewalk, the dark summer awning, or the grayed snowdrift—you can see all these things in their temporary separateness, all connected underneath in such a troubling, satisfying, necessary, indescribable way. Or you can see rubble. Passing states, a useless variety of passing states. Rubble."Oh, What Avails," from Friend of My Youth

Labels:

Alice Munro,

Notes

Thursday, April 04, 2019

Music Notes: "Idumea"

Charles Wesley, one of the founding fathers of Methodism, is said to have penned some 6,500 hymns, among them "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing." I can't say for sure — not having heard them all — but I suspect he never wrote another as weirdly beautiful as "Idumea":

And am I born to die?The peculiarities begin with the title itself, which seems to have come not from Wesley but from a later arranger. Why "Idumea"? According to reference works, Idumea (or Edom) was an ancient kingdom south of the Dead Sea. It is mentioned in the Bible, though not, as far as I can tell (and I'd welcome an exegesis) in any context that would explain the lyrics above. The noted folklorist A. L. Lloyd, in his liner notes to the version of the song performed by the English folk group the Watersons, thought it unnecessary (or was it impossible?) to explain the allusion.

To lay this body down

And as my trembling spirit fly

Into a world unknown?

A land of deepest shade

Unpierced by human thought

The dreary region of the dead

Where all things are forgot

Soon as from earth I go

What will become of me?

Eternal happiness or woe

Must then my fortune be

Waked by the trumpet's sound

I from my grave shall rise

And see the judge with glory crowned

And see the flaming skies

Then there's the way the song begins: in mid-sentence, in mid-thought. Hymns tend to speak in a collective voice; this one is first-person singular and sounds almost like a monologue spoken in character, along the lines of Spoon River Anthology. Even the hymn's theology seems a tad unorthodox. Christianity, as a religion that offers, in effect, a choice of afterlives, has long alternated in its vernacular forms between a kind of "Joy to the World / God is Love" cheeriness and a darker strain, whether expressed in threats of hellfire and brimstone or in the death-obsessed pessimism of the danse macabre and Blind Willie Johnson's "You Gonna Need Somebody on Your Bond." But Wesley's description of

The dreary region of the deadsounds more like the pagan, antinomian conception of the underworld (peopled by Homer's "exhausted dead") than it does the Christian vision of a place where sinners are sent to be paid back for their misdeeds. Is this because the speaker's voice is supposed to be an ancient, Idumean one? Is it because Wesley, though an evangelist and missionary, was also a classically educated scholar for whom the tropes of Greek and Roman literature would have been part of his intellectual training? Or was Wesley, good Methodist, really a secret Modernist avant la lettre (Pound's Cantos, after all, also begins with "And …")? All the elements are there: cryptic reference to antiquity, fragmented monologue …

Where all things are forgot

According to Lloyd, the hymn fell out of favor in England, but remained popular among parishioners in what he calls "remoter settlements of the Upland Southern states of America." One can only wonder what they made of it.

The above note was originally published in A Common Reader's blog Book Case in 2003. I have dusted it off and revised a few points.

Labels:

Missionaries,

Music,

Watersons

Friday, March 22, 2019

Customer Service Wolf

Three installments from Anne Barnetson's droll comic about the adventures of a lupine bookshop clerk. Having served in that role for many years in an earlier phase of my life I can vouch for its essential accuracy.

Labels:

Bookselling,

Comics

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)