Sunday, July 09, 2023

Thursday, June 15, 2023

Findings

Miscellaneous sightings from June wanderings. From top: self-portrait with kodama; white morph of pink lady's-slipper; trailside shrine with Buddhas and rabies tag; forest fungi.

Labels:

Fungi,

Hayao Miyazaki

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Reading Matter

Over the past few weeks we've been in the midst of major preparations for an upcoming relocation, but a few days ago I realized that I had gotten a bit ahead of things and packed up almost our entire library, leaving only a handful of books, all of which I'd read before, with two weeks still to go. Fortunately, our local library just had a book sale (partially with our donations), and at this point they're giving away what's left. I stopped by, took a look around, and saw more than I expected. Any other time I might have loaded up, but I had to focus on immediate needs only. I passed, therefore, on two volumes of Chekhov stories, Charlotte Brontë's The Professor, a Mary Braddon novel I knew nothing about, Iris Murdoch's The Sea, The Sea, a Dickens novel I don't own, and several other tempting volumes, and settled on three. The first two were obligatory; Seamus Heaney and Mark Strand have long been two of my favorite poets, and the books I found were slender, which is definitely a plus right now. I've read parts of Sweeney Astray in other Heaney collections, but was only vaguely aware that Strand had written a brief prose work on Edward Hopper. The real find for me, though, was an apparently unread copy of the Bantam edition (c. 1970) of Herman Hesse's last novel, which has been on and off my "to read" list for years. I've actually never read much Hesse, but I'm old enough to remember the time in the 1960s when no sensitive young person's backpack would be complete without a couple of Noonday Press editions of his work. Why this one in particular? Because the premise ("a chronicle of the future about Castalia, an élitist group formed after the chaos of the 20th-century wars") seemed promising, because Gide, Mann, and T. S. Eliot all admired it, and maybe most of all because how can one resist a title as sonorous as Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game) (or in German, Das Glasperlenspiel)? I left a couple of bucks for a donation to the library. It's a no-lose proposition. If Magister Ludi turns out to be a snooze, at least it will help me fall asleep at night.

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Song

It's morning

Nobody's up but the crows

Memphis Minnie and Joe McCoy

are singing "Can I Do It For You?"

as if they were here in the room

not as if they were dead and buried

these fifty years

As if every breath and every smile

and every finger's touch on the strings of a guitar

hadn't risen up

wrapped in wisps of smoke

and disappeared long ago

into the bustle of a forgotten morning

a thousand miles from here

The sun's just a yellow gash

on the cusp of the horizon

but already the day is opening out

pale and wide and unforgiving

but the worst of winter is done

and somebody somewhere is making coffee

or falling in love

Or anyway falling into their clothes

and Memphis Minnie and Joe McCoy

are playing "North Memphis Blues"

because that's what you do

on some cold morning

when nobody's watching

the smoke rise into the air

Monday, April 17, 2023

A Small Rain's A-Gonna Fall

A lovely and curious turn of phrase with a story behind it almost slipped my notice when I was re-reading Rafi Zabor's novel The Bear Comes Home. Two men, Jones and Levine, stand outside a jazz venue that Levine is constructing within the body of the Brooklyn Bridge.

They stood on the large square landing atop the roughed-out stairway and looked riverward across to Brooklyn. It was an indecisive afternoon: the small rain down had rained and now, south on their right to the Battery, a white winter sun alternately masked and unmasked itself behind migrating cloud. The grey underside of the bridge soared out over the river and diminished toward its farther landing, the water beneath the bridge dull as lead except where the sun found it and tipped the surface. (Emphasis added.)The words "the small rain down had rained," which puzzled me at first, are an allusion to this haunting little fragment of 16th-century song lyric:

Westron wynde when wyll thow blowThe interpretation of the lines and even the parsing of the syntax is somewhat uncertain, but "the small rain down can rain" should probably be read as meaning "the small rain can rain down." The ultimate source of the phrase may be from Deuteronomy (KJV): "My doctrine shall drop as the rain, my speech shall distil as the dew, as the small rain upon the tender herb, and as the showers upon the grass." Thomas Pynchon's first short story was entitled "The Small Rain," and Pynchon scholar Richard Darabaner (1952-1985) believed that he borrowed the title directly from Deuteronomy.

the smalle rayne downe can Rayne

Cryst yf my love were in my Armys

and I yn my bed Agayne

There's a discussion of "Westron Wynde" at Early Music Muse.

Labels:

Rafi Zabor

Friday, March 31, 2023

Freedom down the bending avenue

Songwriter Peter Case has a new record just out from Sunset Blvd Records. Entitled Doctor Moan, it's his first album of original songs since HWY 62 in 2015, and his first ever on which the piano, rather than the guitar, serves as his primary instrument. The shift isn't entirely unprecedented, since two years ago he alternated a bit between the two instruments on a collection of covers of folk songs and blues called The Midnight Broadcast, but still, it's a move into new songwriting territory. It's not entirely a clean break, as there's one tuneful guitar-driven track, "Wandering Days," that wouldn't have been out of place with his work with the Nerves in the mid-1970s. Most of the record, though, draws as much from the postwar generation of jazz pianists like Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans, and McCoy Tyner, as well as bits of classic gospel, soul, and blues, as it does from pop and rock. (As it happens, Case has been sitting in on piano now and then at the Saint John Coltrane Church in San Francisco, and he's been known to sneak in a few bars of "Blue Monk" during warm-ups.)

My favorite track so far, "Have You Ever Been in Trouble?" is built around a few gorgeous dark chords and makes delicious use of the piano's lowest keys. Like much of his songwriting, it explores the world of the down and out (in the West Coast style familiar from Charles Bukowski and Tom Waits) while at the same time weighing the possibilities for redemption. The bridge here is particularly lovely, both tonally and lyrically:

"Downtown Nowhere's Blues" engagingly captures the denizens of a joint called the Round-the-Clock Diner:

There are some interesting reverberations between these two songs: "Have You Ever Been in Trouble?" speaks of "the Holy Ghost / Coming down the alley / Just like a megadose," while a woman in "Downtown Nowhere's Blues" who is on "a microdose of LSD / [...] fiddles with the jukebox and her destiny." Different paths, different revelations.

Other than Case's piano and the one guitar-based track, the instrumentation on Doctor Moan is sparse but effective; it features Jon Flaugher on bass and Chris Joyner on organ. The cover art depicts the vintage Steinway upright Case used to record the album. This is definitely a record worth checking out.

My favorite track so far, "Have You Ever Been in Trouble?" is built around a few gorgeous dark chords and makes delicious use of the piano's lowest keys. Like much of his songwriting, it explores the world of the down and out (in the West Coast style familiar from Charles Bukowski and Tom Waits) while at the same time weighing the possibilities for redemption. The bridge here is particularly lovely, both tonally and lyrically:

There's freedom down the bending avenue

Do you see someone coming?

Something you can do?

There's one thing I know for sure is real

The moment you surrender

The wounds begin to heal

Here's your reprieve

Ask and you'll receive

"Downtown Nowhere's Blues" engagingly captures the denizens of a joint called the Round-the-Clock Diner:

Out front by the curb they're making noise

A bunch of old men that act like boys

Big T turns to me while I'm try'na chew

Says "If I had a dog half as ugly as you

I'd make him walk backward through Downtown Nowhere"

There are some interesting reverberations between these two songs: "Have You Ever Been in Trouble?" speaks of "the Holy Ghost / Coming down the alley / Just like a megadose," while a woman in "Downtown Nowhere's Blues" who is on "a microdose of LSD / [...] fiddles with the jukebox and her destiny." Different paths, different revelations.

Other than Case's piano and the one guitar-based track, the instrumentation on Doctor Moan is sparse but effective; it features Jon Flaugher on bass and Chris Joyner on organ. The cover art depicts the vintage Steinway upright Case used to record the album. This is definitely a record worth checking out.

Labels:

Music,

Peter Case

Thursday, March 16, 2023

The Hearts of Literary Men

Dard Hunter:

Legend has it that Emperor Wu (A.D. 1368-98 ) tried to procure a suitable paper for the printing of money and to this end consulted with the wise men of his realm for advice. One of the learned group suggested that counterfeiting could only be prevented by mixing the macerated hearts of great literary men with the mulberry-bark pulp. The Emperor is said to have taken this suggestion under advisement, but at length he decided it would be a grave mistake to destroy the literary men of China simply for the purpose of using their hearts as ingredients for paper. In talking over the problem with the Empress she suggested that the same result could be achieved without interfering with the lives of their scholarly subjects. The Empress brought forth the thought that the heart of any true literary man was actually in his writings. Therefore, the wise Empress asked the Emperor to have collected the papers upon which the great Chinese authors and poets had set down their writings. The manuscripts were duly macerated and added to the mulberry bark and it was thought that the dark grey tone of the money papers was due to the black ink used in the calligraphy upon the paper.

Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft

Friday, March 10, 2023

Dream House

In an era of computer animation wizardry it's nice to see older technologies like stop-motion animation being reinvigorated and put to use for intelligent visual storytelling. A few months ago we were pleasantly surprised by Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio, and just last night we stumbled upon this little gem. Written by Enda Walsh, The House is made up of three narratives supervised by three different directors, with the common thread being the title building and how it embodies both the nightmarish aspects of home ownership and our insistent need for a place to hang our hats. (For reasons I won't go into, we found it uncannily appropriate to our circumstances.)

The first segment begins in folktale fashion with a poor couple who, after an encounter with a mysterious stranger, find themselves in free possession of a rambling mansion in the British countryside, the only requirement being that they surrender the smaller house that is their own. The focus of the segment is on the older of the couple's two young daughters, who, like Chihiro in Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away, is more alert to the dangers of temptation then her parents are. Increasingly creepy as it progresses, it is the only part of the film that features human subjects, here represented by doll-like and delicate figures whose faces convey boundless melancholy.

By the second segment, the rural landscape has become urbanized and contemporary, and the house is in the possession of an ambitious developer (literally, a rat) who has furnished it with the latest mod cons in the hopes of making a killing in the real estate market. When the house is ready for showing everything possible goes wrong, and, what's worse, two sinister creatures — are they rodents, or something unimaginably worse? — take up residence uninvited and show no sign of leaving.

In the final segment, the house has become isolated by rising seas and is now owned by a long-suffering cat named Rosa, who struggles to maintain it and run it as an apartment building with little help from her two tenants, neither of whom pays cash rent. Gentler and more wistful than the other two parts, it ends in a way that is ultimately liberating.

Here and there I sensed affinities with, but rarely overt allusions to, everything from Kafka's The Metamorphosis, Stanley Kubrick's The Shining, and Miyazaki's Howl's Moving Castle to the scratchboard artist Thomas Ott and Terhi Ekebom's lovely graphic story Logbook. The trailer below gives a good idea of the film's visual styles, but, inevitably, exaggerates its pace. The film largely avoids the lamentable tendency of contemporary animation to fill every possible second of running time with frenetic activity. When the story is sound to begin with there's little need for all of that.

The first segment begins in folktale fashion with a poor couple who, after an encounter with a mysterious stranger, find themselves in free possession of a rambling mansion in the British countryside, the only requirement being that they surrender the smaller house that is their own. The focus of the segment is on the older of the couple's two young daughters, who, like Chihiro in Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away, is more alert to the dangers of temptation then her parents are. Increasingly creepy as it progresses, it is the only part of the film that features human subjects, here represented by doll-like and delicate figures whose faces convey boundless melancholy.

By the second segment, the rural landscape has become urbanized and contemporary, and the house is in the possession of an ambitious developer (literally, a rat) who has furnished it with the latest mod cons in the hopes of making a killing in the real estate market. When the house is ready for showing everything possible goes wrong, and, what's worse, two sinister creatures — are they rodents, or something unimaginably worse? — take up residence uninvited and show no sign of leaving.

In the final segment, the house has become isolated by rising seas and is now owned by a long-suffering cat named Rosa, who struggles to maintain it and run it as an apartment building with little help from her two tenants, neither of whom pays cash rent. Gentler and more wistful than the other two parts, it ends in a way that is ultimately liberating.

Here and there I sensed affinities with, but rarely overt allusions to, everything from Kafka's The Metamorphosis, Stanley Kubrick's The Shining, and Miyazaki's Howl's Moving Castle to the scratchboard artist Thomas Ott and Terhi Ekebom's lovely graphic story Logbook. The trailer below gives a good idea of the film's visual styles, but, inevitably, exaggerates its pace. The film largely avoids the lamentable tendency of contemporary animation to fill every possible second of running time with frenetic activity. When the story is sound to begin with there's little need for all of that.

Sunday, February 19, 2023

"Dark deeds of licentiousness and vice"

"Sometime in March last, a gentleman who lives in Portsmouth N. H., being on a visit to Boston, was induced by a friend of this city, to visit, out of curiosity, the third row, in the Tremont Theatre. In all cities, this part of the theatre is well understood to be the resort of the very dregs of society. Here the vile of both sexes meet together, and arrange their dark deeds of licentiousness and vice. Soon after entering the common hall, this Portsmouth gentleman was struck with the very youthful and innocent countenance of one of the girls in the crowd. He sought an opportunity to speak to her. After some light observations to engage her attention, and not excite any suspicions, but that he was one among the rest, he asked her to walk a little aside, when he inquired how she came to her present condition, &c. He learned that she was from L_______, Vt., that she was very unhappy in her situation, but did not know how to get out of it...

"We warn parents in the country, to be careful about permitting their daughters to go to factories, and especially about coming to Boston. There are men here who have the appearance of gentlemen, who, by the most seductive pretensions, and consummate artifice, seek every opportunity to ruin the innocent and unwary. They do this too, without the least remorse; they even make a boast of their ruined victims. Trust not, then, your daughters here, unless you can secure the watchful care of some well known friend. O how many who have come to this city, innocent and unsuspecting, have been soon snared in the trap of the deceiver, and here found an early, and a dishonorable grave!"

Zion’s Herald, May 9, 1838

Labels:

Boston,

City,

Missionaries

Wednesday, February 01, 2023

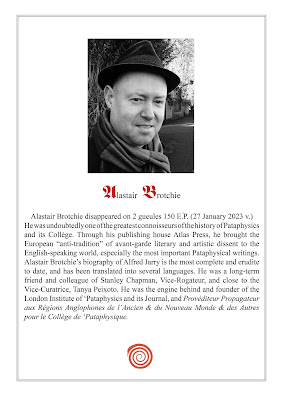

2 gueles 150 E.P.

The writer and publisher Alastair Brotchie has died, according to social media announcements by the Atlas Press, of which he was the proprietor, and the London Institute of Pataphysics, of which he was a guiding spirit and "Secretary of Issuance." The date of his "disappearance" is given, according to the Pataphysical calendar, in the title of this post; according to the Gregorian calendar it was on January 27th of this year.

Brotchie's biography of Alfred Jarry has been near the top of my list of books to read for several years, but I've never quite gotten around to it, in part because our local library system doesn't own a copy. I do have a copy of the Oulipo Compendium he edited with Harry Mathews.

Pataphysics, founded by Jarry, has been defined as "the science of imaginary solutions," and you may make of that what you will. Shortly before the pandemic broke out I took a trip into Manhattan, in part to see the outstanding exhibition at the Morgan Library devoted to Jarry. One can only wonder what he would have made of such a venue for his work, but I like to think he would have been amused. I haven't been back to the city since.

My condolences to Brotchie's family and friends.

Update: The Guardian now has an obituary of Brotchie written by his friend Peter Blegvad.

Brotchie's biography of Alfred Jarry has been near the top of my list of books to read for several years, but I've never quite gotten around to it, in part because our local library system doesn't own a copy. I do have a copy of the Oulipo Compendium he edited with Harry Mathews.

Pataphysics, founded by Jarry, has been defined as "the science of imaginary solutions," and you may make of that what you will. Shortly before the pandemic broke out I took a trip into Manhattan, in part to see the outstanding exhibition at the Morgan Library devoted to Jarry. One can only wonder what he would have made of such a venue for his work, but I like to think he would have been amused. I haven't been back to the city since.

My condolences to Brotchie's family and friends.

Update: The Guardian now has an obituary of Brotchie written by his friend Peter Blegvad.

Sunday, January 22, 2023

Roadside assistance

One summer evening about twenty years ago I left work at rush hour and joined a line of backed-up traffic using the on-ramp to merge onto the parkway I took to get home. Several minutes went by before I made it to the head of the line. The compact car immediately in front of me, driven by a woman who looked to be in her thirties, had no choice but to come to a complete stop and wait for an opening, to the considerable frustration of the drivers behind us, some of whom had started leaning on their horns. I could see the woman leaning anxiously out her open side window, intently watching the cars to her left until, finally, a car moved into the center lane and let her out. The gap was small, however, and so she immediately floored it to get up to speed with the flow of the oncoming cars. What she didn't see, and had no reason to expect, was that two bicyclists, who weren't supposed to be on the parkway at all, had crept up on her right and pulled into the highway lane just in front of her.

As soon as she realized what had happened she slammed on her brakes, but the bicycles were moving too slowly and her momentum was already too great. Boxed in to her left, with only a fraction of a second to react, she had nowhere to go but over the curb to her right. Her car lurched onto the grass border, flattened a small bush, and came to rest at the base of an overpass some ten yards from the pavement.

I had kept my foot on the brake pedal while I watched all this happen, but when the lane opened up I crept out, then carefully pulled off the road onto the grass. So did the car immediately behind me, which was a tan Ford station wagon that looked like it had seen better days. The bicyclists, in the meantime, had heard tires squeal and stopped along the curb to look back. I turned off the engine, walked over to the woman's car, and asked her if she was okay. She said she was but she seemed dazed, distraught. I stepped back a bit, uncertain, half-expecting a cop to come along and sort it all out. After a moment, when nothing seemed to be happening, a heavy-set Black man in his fifties got out of the station wagon and walked, with a barely perceptible limp that suggested a painful hip, over to the woman's car. Even before I noticed the instrument case in the back of the station wagon, I had no trouble recognizing the bass player and composer Clifford Margen. I had seen pictures of him in jazz periodicals and even in a spread in Life magazine. I had a few of his records, one of which some record company marketing whiz had unimaginatively entitled Margenalia. I also knew that he had a reputation for what one writer, with no particular axe to grind, had called "truculence and unpredictability."

The woman tensed visibly as the man approached, but as soon as he spoke to her she relaxed, again said that she was okay, and leaned back against the headrest. He walked around the car once to make sure there was no damage, but by the time he got back to the driver's window he could see that she was sobbing. I couldn't make out his words, but whatever they were they seemed to help and soon she was more composed. He had her take some deep breaths and eventually she managed an embarrassed smile. When it was clear that she was all right he glared briefly at the bicyclists, who were quietly slipping off, and also at me, then got in his car, started the ignition, flipped on his four-way flashers, and crept back to the curb. He waited until the woman had started her car, then put his arm out the window to hold back traffic and let her pull out ahead of him. When they were gone I got into my car and drove off as well.

There was an office party at work the next day, and while chatting with my colleagues I told several of them about the incident. They were about evenly divided between those who shook their heads over the woman's bad driving and those who deplored the presence of bicyclists on a road where they had no business to be. Just one of them recognized the name of Clifford Margen, and he wasn't sure what instrument he played: tenor sax, maybe? Only on the way home that night did I remember what I had, in truth, known perfectly well all along, namely that Clifford Margen had been dead for twenty years, the victim of a landslide on a deserted mountain road somewhere northwest of Mexico City. Even so, I had no doubt about my identification, just as I have no doubt, even now, that there's a tan Ford station wagon somewhere out there driven by a heavy-set Black man who's heading for his next gig and rescuing travelers along the way.

Tuesday, January 03, 2023

You May Leave but This Will Bring You Back

The Memphis Jug Band was a shifting collection of African-American musicians that recorded some 70 or 80 sides of music between 1927 and 1934. Its guiding force was a singer, guitarist, and harmonica player named Will Shade. Other members tended to come and go, although kazoo player Ben Ramey and the guitarist (and ebullient vocalist) Charlie Burse were mainstays. Their music represented a strain of Black entertainment that was popular in its heyday in the 1920s and '30s but which is often forgotten or dismissed today, although a loyal corps of fans, collectors, and musicians have succeeded in keeping much of it in print for those who seek it out. Compared to saxes, electric guitars, and keyboards, kazoos and jugs just aren't generally regarded as being "serious" musical instruments, setting aside the fact that the band also employed acoustic guitar, banjo, mandolin, fiddle, and Will Shade's brilliant harmonica.

The first Memphis Jug Band compilation I owned was a two-LP album issued by Yazoo Records, which I must have bought not long after it was released in 1979. It had 28 tracks, good remastering, liner notes by the respected blues scholar Bengt Olsson, and some colorful front and back cover art by R. Crumb (who also created the trading card shown at the top of this post). I got a lot of spins out of the Yazoo set but once CDs came along I started looking around for something I could play in the car, which is where I do most of my listening. (I can't comfortably read, converse, or even think with music in the background, but I can drive.) The Yazoo albums were eventually transferred to CD, minus five tracks, but I opted instead for a 36-track set from a label called Blues Classics. That label, which I think is now defunct, apparently had some sort of arrangement with Document Records, the big daddy in prewar American music re-issues, which originally was based in Austria. The Blues Classic set had perfunctory liner notes, but the tracks were well-chosen and it was cheap. I got twenty years out of it. Still, there were a few songs I remembered from the Yazoo set that I missed hearing. This year I bought myself the 72-track collection on the Acrobat label shown below. Its liner notes, while extensive, lean a bit too much on Wikipedia and other online sources, and it includes some tracks of minor interest, but it's inexpensive and seems to be more or less as comprehensive as the alternatives. (What to include can be a matter for debate, as the band had various aliases and offshoots.) For the completist, Document Records probably has more thorough coverage, but their compilations aren't as conveniently packaged and several now seem to be only available as downloads. Seventy-two tracks should hold me for a while. There are reasons why jug band music went out of favor — advances in musicianship, shifts in popular taste, complicated issues of racial and sexual politics, cultural embarrassment at anything that was perceived as "primitive" — but the best of it still has much to offer. It's lively and inventive, it's historically important to the development of American popular music, but most of all it's just plain exuberant fun. We should avoid nostalgia for the grim conditions of the segregated society in which it was made, but at the same time we shouldn't turn our backs on the vitality of its creators.

The first representative track, below, is from the band's initial session, in 1927. According to Samuel Charters, the vocalist is Will Weldon, but the song is really a showcase for the harmonica and kazoo. "Sun Brimmer" or "Son Brimmer" was a nickname of Will Shade's.

"Cocaine Habit" (1930) finds the band backing Hattie Hart, one of several female vocalists they worked with at various times, the most notable being Memphis Minnie. Shade's harmonica is again featured, and the guitar part is played by Tee Wee Blackman, who is said to have taught Shade the rudiments of the guitar.

"Everybody's Talking About Sadie Green" also from 1930, displays the band's vaudeville side; the lively vocalist is Charlie Nickerson.

Finally, here's one of my favorite tracks, one that's not included in the Acrobat set, probably because it was credited at the time to "the Carolina Peanut Boys." It's also from 1930 and Charlie Nickerson is again the lead vocalist, but it's the infectious instrumental section after the first couple of verses that really makes it sing. Vol Stevens plays the hybrid banjo-mandolin, and Shade once again is on harp. It's hard to resist.

The standard print sources on the Memphis Jug Band are the pioneering writings of Samuel Charters (The Country Blues, Sweet As the Showers of Rain) and Bengt Olsson (Memphis Blues); the latter is hard to find. There is an exhaustive, if somewhat outdated, online discography at Wirz' American Music.

The first Memphis Jug Band compilation I owned was a two-LP album issued by Yazoo Records, which I must have bought not long after it was released in 1979. It had 28 tracks, good remastering, liner notes by the respected blues scholar Bengt Olsson, and some colorful front and back cover art by R. Crumb (who also created the trading card shown at the top of this post). I got a lot of spins out of the Yazoo set but once CDs came along I started looking around for something I could play in the car, which is where I do most of my listening. (I can't comfortably read, converse, or even think with music in the background, but I can drive.) The Yazoo albums were eventually transferred to CD, minus five tracks, but I opted instead for a 36-track set from a label called Blues Classics. That label, which I think is now defunct, apparently had some sort of arrangement with Document Records, the big daddy in prewar American music re-issues, which originally was based in Austria. The Blues Classic set had perfunctory liner notes, but the tracks were well-chosen and it was cheap. I got twenty years out of it. Still, there were a few songs I remembered from the Yazoo set that I missed hearing. This year I bought myself the 72-track collection on the Acrobat label shown below. Its liner notes, while extensive, lean a bit too much on Wikipedia and other online sources, and it includes some tracks of minor interest, but it's inexpensive and seems to be more or less as comprehensive as the alternatives. (What to include can be a matter for debate, as the band had various aliases and offshoots.) For the completist, Document Records probably has more thorough coverage, but their compilations aren't as conveniently packaged and several now seem to be only available as downloads. Seventy-two tracks should hold me for a while. There are reasons why jug band music went out of favor — advances in musicianship, shifts in popular taste, complicated issues of racial and sexual politics, cultural embarrassment at anything that was perceived as "primitive" — but the best of it still has much to offer. It's lively and inventive, it's historically important to the development of American popular music, but most of all it's just plain exuberant fun. We should avoid nostalgia for the grim conditions of the segregated society in which it was made, but at the same time we shouldn't turn our backs on the vitality of its creators.

The first representative track, below, is from the band's initial session, in 1927. According to Samuel Charters, the vocalist is Will Weldon, but the song is really a showcase for the harmonica and kazoo. "Sun Brimmer" or "Son Brimmer" was a nickname of Will Shade's.

"Cocaine Habit" (1930) finds the band backing Hattie Hart, one of several female vocalists they worked with at various times, the most notable being Memphis Minnie. Shade's harmonica is again featured, and the guitar part is played by Tee Wee Blackman, who is said to have taught Shade the rudiments of the guitar.

"Everybody's Talking About Sadie Green" also from 1930, displays the band's vaudeville side; the lively vocalist is Charlie Nickerson.

Finally, here's one of my favorite tracks, one that's not included in the Acrobat set, probably because it was credited at the time to "the Carolina Peanut Boys." It's also from 1930 and Charlie Nickerson is again the lead vocalist, but it's the infectious instrumental section after the first couple of verses that really makes it sing. Vol Stevens plays the hybrid banjo-mandolin, and Shade once again is on harp. It's hard to resist.

The standard print sources on the Memphis Jug Band are the pioneering writings of Samuel Charters (The Country Blues, Sweet As the Showers of Rain) and Bengt Olsson (Memphis Blues); the latter is hard to find. There is an exhaustive, if somewhat outdated, online discography at Wirz' American Music.

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Hearst and the Devil Fish

Phoebe Hearst didn't care for her son's taste in women. Throughout his adult life, the media magnate William Randolph Hearst had a taste for showgirls and lived more or less openly with mistresses even while raising a family of five sons with his legal wife, Millicent (another showgirl). While still in his twenties, he had come close to marrying an aspiring actress named Eleanor Calhoun. Though Phoebe had actually introduced the two, she regarded Calhoun as a golddigger and firmly opposed their union. Young "Will" Hearst, at that point, had ambition but little money of his own. His father was a wealthy mining entrepreneur who eventually became a US senator, but he was absent much of the time, marginally literate, and averse to correspondence; it was Phoebe, originally a Missouri schoolteacher, who kept tabs on things. In 1887 she wrote to a friend:

It turns out that the term "devil-fish" or "devilfish" has been applied to a bewildering range of creatures, from gray whales to manta rays, but the animal Phoebe had in mind was neither fish nor cetacean but a cephalopod. Had she been inclined, she could have read an 1875 book by Henry Lee, the keeper of the Brighton Aquarium, entitled The Octopus, Or, The "Devil-fish" of Fiction and of Fact. One chapter of Lee's book retells a portion of Victor Hugo's novel Les Travailleurs de la mer, which describes a life-and-death struggle between a Guernsey fisherman and a giant octopus. Phoebe, who was well-travelled and who is known to have studied French as an adult, may well have been familiar with Hugo's account, in translation or in the original, and if not no doubt she had heard similar stories.

Once the "Devil fish" has been identified, the metaphor starts to make sense. Phoebe saw Eleanor Calhoun as a sinister monster threatening to enfold Will in her lethal embrace. But what about the "toils"?

My first thought was that Hearst's biographer, David Nasaw, had mistranscribed Phoebe's letter, and that what she really wrote was "coils of the Devil fish," referring to its tentacles. But Nasaw is a careful researcher and his book is well-edited; surely the error, if it were such, would have been spotted early on. I then supposed that Phoebe meant to write "coils" but had slipped and written "toils," perhaps with Hugo's "toilers" in the back of her mind. As it turns out, however, there's no need for creative speculations. Phoebe wrote "toils" because she meant "toils"; the word "toil" has an archaic meaning of "net, snare," related to the French toile. In a 19th-century translation of Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame a fly is said to be "caught in the toils of the spider." The octopus idiom seems to have been in the air; in 1897 a writer named Owen Hall, who certainly hadn't read Phoebe's letter, used the identical words in a short story entitled "In a Treasure Ship."

A similar molluscan metaphor would inspire Frank Norris's 1901 novel about the California railway industry, The Octopus.

Illustration: painting by Victor Hugo

I am so distressed about Will that I don't really know how I can live if he marries Eleanor Calhoun. She is determined to marry him and it seems as if he must be in the toils of the Devil fish.The last phrase is odd. What was a Devil fish, and what labors did it undertake? Why would it be an apt metaphor for a woman who, in Phoebe's view, was out to ensnare her son?

It turns out that the term "devil-fish" or "devilfish" has been applied to a bewildering range of creatures, from gray whales to manta rays, but the animal Phoebe had in mind was neither fish nor cetacean but a cephalopod. Had she been inclined, she could have read an 1875 book by Henry Lee, the keeper of the Brighton Aquarium, entitled The Octopus, Or, The "Devil-fish" of Fiction and of Fact. One chapter of Lee's book retells a portion of Victor Hugo's novel Les Travailleurs de la mer, which describes a life-and-death struggle between a Guernsey fisherman and a giant octopus. Phoebe, who was well-travelled and who is known to have studied French as an adult, may well have been familiar with Hugo's account, in translation or in the original, and if not no doubt she had heard similar stories.

Once the "Devil fish" has been identified, the metaphor starts to make sense. Phoebe saw Eleanor Calhoun as a sinister monster threatening to enfold Will in her lethal embrace. But what about the "toils"?

My first thought was that Hearst's biographer, David Nasaw, had mistranscribed Phoebe's letter, and that what she really wrote was "coils of the Devil fish," referring to its tentacles. But Nasaw is a careful researcher and his book is well-edited; surely the error, if it were such, would have been spotted early on. I then supposed that Phoebe meant to write "coils" but had slipped and written "toils," perhaps with Hugo's "toilers" in the back of her mind. As it turns out, however, there's no need for creative speculations. Phoebe wrote "toils" because she meant "toils"; the word "toil" has an archaic meaning of "net, snare," related to the French toile. In a 19th-century translation of Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame a fly is said to be "caught in the toils of the spider." The octopus idiom seems to have been in the air; in 1897 a writer named Owen Hall, who certainly hadn't read Phoebe's letter, used the identical words in a short story entitled "In a Treasure Ship."

A similar molluscan metaphor would inspire Frank Norris's 1901 novel about the California railway industry, The Octopus.

Illustration: painting by Victor Hugo

Thursday, November 03, 2022

Shuna's Journey (2022)

First Second Books in the US has released the first authorized English-language translation of Hayao Miyazaki's 1983 full-color manga Shuna no tabi (Shuna's Journey). I've written about the original Japanese version at length before (link); I speak no Japanese but was able to follow the story with the help of earlier fan translations. The readable new translation, by Alex Dudok de Wit, clears up a few points in the narrative here and there. The New York Times has a review. I'll confine myself below to a few technical points about the reproduction.

The American edition, printed in Singapore, respects the layout and orientation of the Japanese edition, that is, printing it back-to-front from a US perspective. The trim size has been increased by about 50% with a noticeable but not glaring decrease in sharpness, and unlike the original, which was a paperback, the book has a hardcover binding, which makes it easier to see into the gutter. The paper stock isn't coated, however, and the color palette, particularly the lovely rich blues of Miyazaki's original, is a bit washed out. Whatever image processing magic was required to replace the Japanese text with English seems to have gone smoothly. Devotees may want to seek out the Japanese edition (ISBN 9784196695103), which should be obtainable for under $20, so that they can appreciate the full beauty of the original in tandem with this welcome and overdue translation.

The American edition, printed in Singapore, respects the layout and orientation of the Japanese edition, that is, printing it back-to-front from a US perspective. The trim size has been increased by about 50% with a noticeable but not glaring decrease in sharpness, and unlike the original, which was a paperback, the book has a hardcover binding, which makes it easier to see into the gutter. The paper stock isn't coated, however, and the color palette, particularly the lovely rich blues of Miyazaki's original, is a bit washed out. Whatever image processing magic was required to replace the Japanese text with English seems to have gone smoothly. Devotees may want to seek out the Japanese edition (ISBN 9784196695103), which should be obtainable for under $20, so that they can appreciate the full beauty of the original in tandem with this welcome and overdue translation.

Labels:

Hayao Miyazaki,

Japan

Wednesday, November 02, 2022

Building Stonehenge (George Booth 1926-2022)

My favorite Booth cartoon, this one didn't appear in the New Yorker but in the business section of the New York Times, accompanying an article about corporate downsizing. I scanned it years ago but missed a sliver at the bottom.

Labels:

Cartoons,

George Booth,

Stonehenge

Saturday, October 22, 2022

Invasion

I'm standing on a great plain with no trees or buildings in sight, and I notice a faint hum of engine noise. I look up. Airplanes or airships that must be of enormous size, though they are barely dots because they are so high, are flying in formation across a crystalline, cloudless sky, leaving tiny, precise contrails miles above me. They seem not to have come from any of the cardinal points but simply to have descended from the stratosphere. As I watch I see white parachutes emerging, opening and hanging in the air like dandelion seeds, but the skydivers don't descend; they simply hover in space, dancing and parading together, held aloft no doubt by powerful high-altitude winds.

A crowd has gathered. I hear the cough of a police radio at my back and air-raid sirens somewhere in the distance. Strobe lights flicker. Military vehicles appear, steered by grim-faced men in helmets and dark glasses.

The aircraft are moving over our heads at what must be terrific speed, though from the ground they barely seem to creep. The parachutists, too, are drifting away, still whirling in tight patterns and showing no sign of coming to earth. The crowd thins and the vehicles race off and disappear from sight. The plain darkens as the sun falls behind distant mountains. All is quiet.

Labels:

Amusements

Beyond

This was not a dream, although it seemed a bit like one at the time. On a beautiful fall afternoon I drove a few miles to one of my favorite haunts, a preserve of some 600 or so acres of woodland dotted with rocks and a couple of little ponds and streams. I brought my camera along as I usually do on my hikes, but there wasn't much to see except fallen leaves. I walked a couple of miles without meeting anyone else, then, having climbed a hill to the highest point in the preserve and briefly rested on a bench, I got set to head back.

I came to a place where the trail bends to the left and descends to what on the map is called a lake but is really just a modest pond. Just at the bend, though, I saw something that had never been there on my previous visits: a trail off to the right, clearly marked with red blazes on trees and carefully bordered with lengths of pruned branches. Intrigued, I started down the trail and followed it up to the top of a ridge, figuring that it couldn't take me very far out of my way. I continued along as it wound through the woods, crossed old stone walls, and wove around ancient outcroppings of rock. At one point I passed the remains of some kind of structure, though it would be hard to say just what it had been.And the trail went on and on. I kept expecting it to loop back to the main trail, or if not, just to come to a dead end. But I started to think: What if it doesn't? What if it never comes back? What if it just keeps going?

I lost the trail once or twice because I was paying attention to the contours of the terrain instead of the blazes, but quickly found the right course again. Eventually I got a bead on where I was in relation to the rest of the preserve, and descended a series of what looked like old stone steps at the top of a long slope that, sure enough, met up with the main trail at an intersection that, like the first, had never been there before. I had detoured about a mile. An improvised sign posted at the intersection noted the opening of the trail, and the recent purchase of a new parcel of land that made it possible, but when I got back to the main kiosk at the parking lot the map there hadn't been updated and there was no notice posted about any extension of the trail system. I almost wonder whether that trail will be there the next time I visit.

I came to a place where the trail bends to the left and descends to what on the map is called a lake but is really just a modest pond. Just at the bend, though, I saw something that had never been there on my previous visits: a trail off to the right, clearly marked with red blazes on trees and carefully bordered with lengths of pruned branches. Intrigued, I started down the trail and followed it up to the top of a ridge, figuring that it couldn't take me very far out of my way. I continued along as it wound through the woods, crossed old stone walls, and wove around ancient outcroppings of rock. At one point I passed the remains of some kind of structure, though it would be hard to say just what it had been.And the trail went on and on. I kept expecting it to loop back to the main trail, or if not, just to come to a dead end. But I started to think: What if it doesn't? What if it never comes back? What if it just keeps going?

I lost the trail once or twice because I was paying attention to the contours of the terrain instead of the blazes, but quickly found the right course again. Eventually I got a bead on where I was in relation to the rest of the preserve, and descended a series of what looked like old stone steps at the top of a long slope that, sure enough, met up with the main trail at an intersection that, like the first, had never been there before. I had detoured about a mile. An improvised sign posted at the intersection noted the opening of the trail, and the recent purchase of a new parcel of land that made it possible, but when I got back to the main kiosk at the parking lot the map there hadn't been updated and there was no notice posted about any extension of the trail system. I almost wonder whether that trail will be there the next time I visit.

Labels:

Walking

Wednesday, October 12, 2022

On the road

About twenty years ago or maybe a little more, my wife and I went to a small music club called the Towne Crier, which at that time was located in Pawling, New York, to hear a Scottish traditional music group called the Tannahill Weavers. According to a rumor I heard later, the Tannies had just come off a gig in a different venue at which some ignorant louts of the kind who think that anything connected with Scotland is fair game for mockery had made it an utterly miserable night for the group, so they may have come onstage with just a wee bit of trepidation. The Towne Crier, however, was a club for people who are knowledgeable about and serious about their music. As soon the Tannies finished the first song (or maybe set of tunes), the audience of some 150 or 200 people went absolutely wild in the best way, cheering and applauding and maybe even leaping to their feet, and I'll never forget the looks the band members exchanged in that moment, looks of mingled delight, relief, and stupefaction at their reception. Needless to say they were energized for the rest of the evening and put on a great show. As of 2022 they're still regular vistors to the Crier, which has since moved a bit west to Beacon.

The Tannahill lineup that night (it has changed often over the years) was presumably Roy Gullane on lead vocals and guitar, Phil Smillie on whistle, flute, and vocals, Leslie Wilson on guitar, bouzouki, and vocals, John Martin on fiddle and vocals, and I think Duncan Nicholson on bagpipes. The inclusion of the pipes was an innovation introduced by the group, and takes a bit of careful arranging, since bagpipes are just naturally louder than the stringed instruments and aren't traditionally played in a combo setting. (The Irish group Planxty, which had an approach somewhat akin to that of the Tannies, made similar creative use of Liam O'Flynn's uilleann pipes.)

The Tannies play a mixture of instrumentals, old ballads, and original songs, driven by Gullane's vocals and energetic rhythm guitar work, which really has to be seen live to be appreciated in full. Gullane has just put out a memoir entitled Goulash Soup and Chips, in which he tells stories from tours past, some painful (miserable road trips, gigs that weren't paid for, baggage handling disasters, etc.) and others absolutely hilarious. It's available from Amazon or at Tannahill Weavers gigs, and is essential for fans of the group and recommended for anyone interested in traditional music. Long may they wave.

Below is a clip of an expanded line-up of the Tannies performing "The Geese in the Bog" a few years back during a 40th-anniversary celebration.

The Tannahill lineup that night (it has changed often over the years) was presumably Roy Gullane on lead vocals and guitar, Phil Smillie on whistle, flute, and vocals, Leslie Wilson on guitar, bouzouki, and vocals, John Martin on fiddle and vocals, and I think Duncan Nicholson on bagpipes. The inclusion of the pipes was an innovation introduced by the group, and takes a bit of careful arranging, since bagpipes are just naturally louder than the stringed instruments and aren't traditionally played in a combo setting. (The Irish group Planxty, which had an approach somewhat akin to that of the Tannies, made similar creative use of Liam O'Flynn's uilleann pipes.)

The Tannies play a mixture of instrumentals, old ballads, and original songs, driven by Gullane's vocals and energetic rhythm guitar work, which really has to be seen live to be appreciated in full. Gullane has just put out a memoir entitled Goulash Soup and Chips, in which he tells stories from tours past, some painful (miserable road trips, gigs that weren't paid for, baggage handling disasters, etc.) and others absolutely hilarious. It's available from Amazon or at Tannahill Weavers gigs, and is essential for fans of the group and recommended for anyone interested in traditional music. Long may they wave.

Below is a clip of an expanded line-up of the Tannies performing "The Geese in the Bog" a few years back during a 40th-anniversary celebration.

Labels:

Music,

Scottish,

Tannahill Weavers

Thursday, October 06, 2022

Macario

I enjoyed this seasonally appropriate 1960 Mexican film directed by Roberto Gavaldón, with cinematography by Gabriel Figueroa. Macario is based on a short story by B. Traven, which is in turn based on a folktale called (in one of its many versions) "Godfather Death." It tells of a poor woodcutter (Ignacio López Tarso) who can barely feed his family enough tortillas and beans to fill their stomachs. Since his one wish in life is to have an entire roast turkey for himself, his devoted wife (Pina Pellicer) finally steals one and cooks it for him. As he sits down to eat it he receives in succession three visitors, whom we realize are in turn the Devil, God (or Jesus), and Death. Each asks to share his meal, but on the basis of some quite logical reasoning he agrees to invite only the third, who, in return, gives Macario a magic liquid that will enable him to cure the dying. There is a catch, however; if Macario sees Death standing at the feet of the patient, he may perform his cure; if Death stands at the head of the bed, the patient is his and Macario must not intervene. Macario makes use of the potion and becomes, in time, a rich man, until the Inquisition gets wind of his activities.

One of the things I liked about the film is that it plays down the potentially garish visual aspect of the story. (That aspect is, in part, reserved for the opening credits, which feature a troupe of folkloric skeleton marionettes.) The Devil, for instance, is a bit of a snazzy dresser, but he doesn't have horns and a goatee, nor is Death a skeletal figure with a flail. Macario, in his unassuming way, recognizes them for who they are nevertheless, and he isn't excessively impressed with either, or with the Señor. López Tarso is particularly good at giving Death skeptical looks at the bedside of patients who are obvious goners but whom Death assures him can still be saved. Really, this one? (Shrug.)

Gavaldón made at least two other films based on Traven novels or stories, Rosa Blanca and Días de otoño. I haven't seen either one, although I've read the story the latter is based on and it could be interesting. Ignacio López Tarso, at this writing, is still alive at the age of 97, which suggests that he set aside a bit of that potion for himself. Sadly, Pina Pellicer, who starred in Días de otoño, died at age 30 of an overdose of sleeping pills.

I'm not sure about the current availability of Macario on DVD or from streaming services; I watched an older DVD release that has subtitle options in both English and Spanish. A version of the folktale can be found in the Lore Segal / Maurice Sendak edition of The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm, one of those perfect books that belong in every household.

One of the things I liked about the film is that it plays down the potentially garish visual aspect of the story. (That aspect is, in part, reserved for the opening credits, which feature a troupe of folkloric skeleton marionettes.) The Devil, for instance, is a bit of a snazzy dresser, but he doesn't have horns and a goatee, nor is Death a skeletal figure with a flail. Macario, in his unassuming way, recognizes them for who they are nevertheless, and he isn't excessively impressed with either, or with the Señor. López Tarso is particularly good at giving Death skeptical looks at the bedside of patients who are obvious goners but whom Death assures him can still be saved. Really, this one? (Shrug.)

Gavaldón made at least two other films based on Traven novels or stories, Rosa Blanca and Días de otoño. I haven't seen either one, although I've read the story the latter is based on and it could be interesting. Ignacio López Tarso, at this writing, is still alive at the age of 97, which suggests that he set aside a bit of that potion for himself. Sadly, Pina Pellicer, who starred in Días de otoño, died at age 30 of an overdose of sleeping pills.

I'm not sure about the current availability of Macario on DVD or from streaming services; I watched an older DVD release that has subtitle options in both English and Spanish. A version of the folktale can be found in the Lore Segal / Maurice Sendak edition of The Juniper Tree and Other Tales from Grimm, one of those perfect books that belong in every household.

Labels:

B. Traven,

Film,

Folklore,

Lore Segal,

Maurice Sendak,

Mexico

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)