Friday, February 11, 2022

Bookseller's Nightmare

A prim middle-aged woman steps up to the counter and asks if we have any books by the novelist Catherine Cookson. I say I don't think so but I agree to check the shelf and the stockroom. No Catherine Cookson. She would like to order some. I reach for Books in Print, but the volumes we have on our reference shelf are decades old and the authors volume is missing anyway. I switch on the microfiche reader. The information that is displayed on the screen has nothing to do with books. Instead, there are a series of street-level views of a city, and I can't even find the intersection I'm looking for. In the meantime, someone has set down a plateful of very appetizing-looking chocolates next to the microfiche reader, but who knows when I'll have a chance to try one.

Labels:

Enigmas

Thursday, February 10, 2022

Curiosity Cabinet

This volume of stories, texts, and illustrations was published by Profile Books in 2003. For a while it seemed to have become scarce, but it's relatively easy to find now.

The Wellcome Collection is (or was) a vast assemblage of objects related to the history and anthropology of medicine. As one might expect, many of the objects are gruesome or bizarre. Henry Wellcome, who amassed the objects, died in 1936, and after his death much of the collection was apparently dispersed, though some of its holdings became accessible to the public in 2007. The editors explain the concept:

Oddly, I've found no evidence that either of the two Helen Cleary novels mentioned was ever published, nor any indication that she has published any additional fiction. She didn't disappear; she apparently has contributed to several documentaries and reference books.

In conjunction with the British Museum show, the Quay Brothers released an eccentric short documentary about the collection, which is also entitled The Phantom Museum.

The Wellcome Collection is (or was) a vast assemblage of objects related to the history and anthropology of medicine. As one might expect, many of the objects are gruesome or bizarre. Henry Wellcome, who amassed the objects, died in 1936, and after his death much of the collection was apparently dispersed, though some of its holdings became accessible to the public in 2007. The editors explain the concept:

This book forms a companion volume to the catalogue of an exhibition on Henry Wellcome's collection held at the British Museum in the summer of 2003. The aim of the exhibition was to reunite a fraction of the collection back in one place. The exhibition catalog endeavours to present the facts of the collection, exploring its objects through documents and physical evidence. Here, in The Phantom Museum, the objects are investigated using a different method, that of the sympathetic imagination.Each of the six pieces in the volume is inspired by one or more of the Wellcome's objects. A. S. Byatt is the most familiar name among the writers. Peter Blegvad contributes an unclassifiable piece, but my favorite is a deft short story entitled "The Venus Time of Year," which follows two women, one modern and one in Roman Britain, who both have recourse to votive offerings in the form of a fertility figurine. Admirably, it doesn't try to do too much or look too far ahead in the women's lives. Of the author, the back flap notes, "Helen Cleary lived in Singapore, Wales and East Anglia before moving to London. She is working on her second novel and writes non-fiction for the BBC History website."

Oddly, I've found no evidence that either of the two Helen Cleary novels mentioned was ever published, nor any indication that she has published any additional fiction. She didn't disappear; she apparently has contributed to several documentaries and reference books.

In conjunction with the British Museum show, the Quay Brothers released an eccentric short documentary about the collection, which is also entitled The Phantom Museum.

Monday, February 07, 2022

Time Capsule

Above, a page of ads from Barney Rosset's Evergreen Review, Vol. 2. No. 7 (Winter 1959). This was a themed issue devoted to Mexico, but it also included a long essay on Thelonious Monk, so these particular advertisements were presumably chosen with that in mind. Bongos are more usually associated with Cuba, but these "pre-tuned Mexican bongos" would have been the perfect accessories for beatniks, or at least for the Hollywood version of them. Other ads in this issue included one for the Living Theatre and for the Circle in the Square production of Brendan Behan's Quare Fellow, directed by José Quintero.

Sadly, the Gotham Book Mart is no more, but as of this writing at least one of the contributors, the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska, is still with us after sixty-odd years.

Sadly, the Gotham Book Mart is no more, but as of this writing at least one of the contributors, the Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska, is still with us after sixty-odd years.

Saturday, February 05, 2022

Jason Epstein (1928-2022)

Publishing pioneer Jason Epstein has died. At 93, he managed to outlive his obituarist, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, who died in 2018.

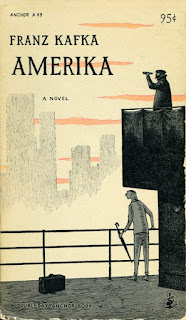

Epstein worked with a long list of authors and founded or co-founded Anchor Books, The New York Review of Books, and the Library of America. I confess to a fetishism for the early Anchor paperbacks, including those published after Epstein left the company in 1958. I have a dozen or so in the house and often re-read some of them. Many have wonderfully dotty covers by Edward Gorey. Today Anchor Books and many of its erstwhile competitors and imitators in the paperback market, including Vintage, Penguin, Signet, Ballantine, Bantam, and Dell, are all subsumed under the same corporate umbrella.

Epstein worked with a long list of authors and founded or co-founded Anchor Books, The New York Review of Books, and the Library of America. I confess to a fetishism for the early Anchor paperbacks, including those published after Epstein left the company in 1958. I have a dozen or so in the house and often re-read some of them. Many have wonderfully dotty covers by Edward Gorey. Today Anchor Books and many of its erstwhile competitors and imitators in the paperback market, including Vintage, Penguin, Signet, Ballantine, Bantam, and Dell, are all subsumed under the same corporate umbrella.

Labels:

Edward Gorey,

Publishing

Monday, January 31, 2022

Norma Waterson (1939-2022)

The revered British folksinger Norma Waterson has died. The Guardian has an obituary and a nice appreciation.

Though she recorded contemporary material as a solo artist, she was probably best known as a member of a family ensemble that in its original conformation in the 1960s also included her brother Mike, sister Lal, and a cousin, John Harrison. Norma's husband, the fine guitarist Martin Carthy (who survives her) replaced Harrison beginning in 1975. Later lineups under various names included the couple's daughter, the fiddler Eliza Carthy.

Below are the Watersons (including Martin Carthy) with a rousing a capella hymn demonstrating the group's unique style.

A documentary entitles Travelling for a Living follows the group in their early days.

Saturday, January 22, 2022

Reading Matter

Henry Mayhew:

I may mention that in the course of my inquiry into the condition of the fancy cabinet-makers of the metropolis, one elderly and very intelligent man, a first-rate artisan in skill, told me he had been so reduced in the world by the underselling of slop-masters (called "butchers" or "slaughterers," by the workmen in the trade), that though in his youth he could take in the News and Examiner papers (each he believed 9d. at that time, but was not certain), he could afford, and enjoyed, no reading when I saw him last autumn, beyond the book-leaves in which he received his quarter of cheese, his small piece of bacon or fresh meat, or his saveloys; and his wife schemed to go to the shops who "wrapped up their things from books," in order that he might have something to read after his day's work.

London Labour and the London Poor

Labels:

Henry Mayhew,

London

Friday, January 21, 2022

Urban legend

Henry Mayhew, the great chronicler of 19th-century London's working poor, collected the following tale in the course of an interview with a lively street "patterer" who specialized in hawking printed broadsides containing accounts of notorious murders:

Camus had come across the incident in an article published by the Hearst Universal Service, which described it as having taken place in Yugoslavia; he included a brief reference to it in The Stranger before developing it into the play. But it was a shopworn tale even in Mayhew's day. Folklorist Veronique Campion-Vincent, in a 1998 article in the Nordic Yearbook of Folklore (PDF here) traces it back to several versions dating from 1618; within three years versions of the tale had variously located the supposed events in London, Languedoc, Ulm (in what is now Germany), and Poland. Clearly it was too good a yarn not to pass on. (Elements of it — the failure to recognize a long-lost family member — arguably date back to Oedipus Tyrannus and the Odyssey.)

Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, incidentally, is a revelation in itself. A contemporary and acquaintance of Dickens, he combined statistical analysis (mostly omitted in the abridged Oxford University Press edition shown above) with oral history to provide a kind of non-fiction counterpart to the work of the great novelist. He keeps the moralizing to a minimum and allows individuals who would have been long forgotten by now to speak in their own voices. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst aptly calls his four-volume work "the greatest Victorian novel never written."

Then there's the Liverpool Tragedy - that's very attractive. It's a mother murdering her own son, through gold. He had come from the East Indies, and married a rich planter's daughter. He came back to England to see his parents after an absence of thirty years. They kept a lodging-house in Liverpool for sailors; the son went there to lodge, and meant to tell his parents who he was in the morning. His mother saw the gold he had got in his boxes, and cut his throat - severed his head from his body; the old man, upwards of seventy years of age holding the candle. They had put a washing-tub under the bed to catch his blood. The morning after the murder the old man's daughter calls and inquires for a young man. The old man denies that they have had any such person in the house. She says he had a mole on his arm in the shape of a strawberry. The old couple go upstairs to examine the corpse, and find they have murdered their own son, and then they both put an end to their existence.I recognized the outlines of the tale immediately: it's more or less the plot of Albert Camus's 1943 drama Le malentendu, usually translated as The Misunderstanding. Camus shifts the action to Czechoslovakia, replaces the homicidal father with a sister, and changes the machinery of the eventual revelation scene, but it's clearly the same basic story.

Camus had come across the incident in an article published by the Hearst Universal Service, which described it as having taken place in Yugoslavia; he included a brief reference to it in The Stranger before developing it into the play. But it was a shopworn tale even in Mayhew's day. Folklorist Veronique Campion-Vincent, in a 1998 article in the Nordic Yearbook of Folklore (PDF here) traces it back to several versions dating from 1618; within three years versions of the tale had variously located the supposed events in London, Languedoc, Ulm (in what is now Germany), and Poland. Clearly it was too good a yarn not to pass on. (Elements of it — the failure to recognize a long-lost family member — arguably date back to Oedipus Tyrannus and the Odyssey.)

Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, incidentally, is a revelation in itself. A contemporary and acquaintance of Dickens, he combined statistical analysis (mostly omitted in the abridged Oxford University Press edition shown above) with oral history to provide a kind of non-fiction counterpart to the work of the great novelist. He keeps the moralizing to a minimum and allows individuals who would have been long forgotten by now to speak in their own voices. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst aptly calls his four-volume work "the greatest Victorian novel never written."

Labels:

Albert Camus,

Folklore,

Henry Mayhew,

London

Monday, January 17, 2022

John the Bear

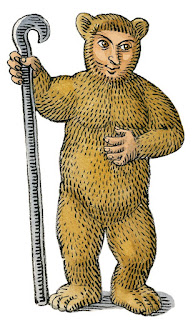

The above illustration by the late French artist Jean-Claude Pertuzé is from a version of a folktale known in French as "Jean de l'ours," that is, John of the Bear or John the Bear. The story of a hero, born to a human mother and an ursine father, who is kept in a cave until he is old enough to roll away the stone that encloses it, and who later descends into the underworld to rescue three princesses, the tale was found throughout Europe and has been carried into the Americas. The German philologist Friedrich Panzer traced a series of parallels between the folktale and the saga of Beowulf, whose name may mean "Bee-wolf," that is, "bear."

The classicist Rhys Carpenter went further, connecting the story, by arguments too intricate to describe here, with the Odyssey, and suggesting a common legendary tradition ultimately deriving from memories of a Eurasian bear-cult. The bear, an animal that immures itself and passes the winter in death-like torpor, has often been conceived of as a messenger to the Other World (as among the Ainu), perhaps as their lord himself. Carpenter mentions the case of the bear-like Thracian hero-god Salmoxis, who, according to Herodotus, built a great hall and regaled his guests with promises of eternal life, before disappearing, apparently dead, into an underground chamber for three years, only to return. In Strabo the same figure becomes co-regent of the underworld.

Is it too much to find here an echo in the New Testament, where the stone is rolled away from the tomb of the risen Jesus after the harrowing of Hell?

The classicist Rhys Carpenter went further, connecting the story, by arguments too intricate to describe here, with the Odyssey, and suggesting a common legendary tradition ultimately deriving from memories of a Eurasian bear-cult. The bear, an animal that immures itself and passes the winter in death-like torpor, has often been conceived of as a messenger to the Other World (as among the Ainu), perhaps as their lord himself. Carpenter mentions the case of the bear-like Thracian hero-god Salmoxis, who, according to Herodotus, built a great hall and regaled his guests with promises of eternal life, before disappearing, apparently dead, into an underground chamber for three years, only to return. In Strabo the same figure becomes co-regent of the underworld.

Is it too much to find here an echo in the New Testament, where the stone is rolled away from the tomb of the risen Jesus after the harrowing of Hell?

Saturday, January 15, 2022

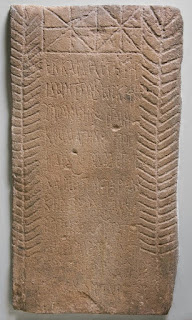

Hermes

Let some traveller, on seeing Hermes of Commagene, aged sixteen years, sheltered in the tomb by fate, call out: I give you my greetings, lad, though mortal the path of life you slowly tread, for swiftly have you winged your way to the land of the Cimmerian folk. Nor will your words be false, for the lad is good, and you will do him a good service.The Hermes in this third-century Greek inscription isn't the winged messenger of the Greek gods but a teenager who died and was memorialized on what is now known as the Brough Stone, preserved in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. (Original Greek text and details here.) He had done some travelling of his own before he met his end in Roman Britain; Commagene, where he was born, was a small kingdom in what is now eastern Turkey. The Cimmerians, to whose land he flies after death, were a barbarian people known, if hazily, to the Classical world, but in the Odyssey Homer locates their country in the dark regions of the far north, just this side of Hades.

Curiously, Robert Fitzgerald doesn't use the word "Cimmerian" (the Greek is Κιμμερίων) in his translation of Book XI, line 14, but refers instead to "the realm and region of the Men of Winter." It's in Pound's Cantos, though:

Came we then to the bounds of deepest water,

To the Kimmerian lands, and peopled cities

Covered with close-webbed mist, unpierced ever

With glitter of sun-rays

Labels:

Homer,

Migrations

Thursday, December 16, 2021

The Whales of the Dead

Stepan Krasheninnikov:

Krasheninnikov's account probably should be better known; he was a pioneering geographer and a capable and relatively unprejudiced anthropologist. Though he was sometimes wrong, as in firmly declaring that whales were fish, there is much of value in his account, which is out of print but not that hard to find. The Oregon Historical Society edition (the only complete English-language version) could have used more explanatory notes but is otherwise a noble undertaking.

Image Credit: "The Volcano of Awatcha (Avacha) in Kamchatka, Siberia." Etching with engraving, from the Wellcome Collection. A different engraving of the same image is reproduced in Explorations of Kamchatka.

The Kamchadals regard Mount Kamchatka as the dwelling place of the dead; they say that when it emits flames, it means the dead are heating up their yurts. According to them, the dead live on whale blubber, trap whales in a subterranean sea, and burn whale oil for light. They use whale bones instead of wood to heat their homes. To support their belief, they say that some of their countrymen have gone into the interior of this mountain, where they saw the habitations of their forebears. Steller says that they consider this mountain the home of spirits. When anyone questions them, he adds, about what goes on in this spirit world, they reply that the spirits cook whales. If they are asked where the spirits got the whales, they reply that the whales came from the sea, that the spirits leave the mountains at night and take so many whales that some bring back as many as five or even ten, one on each of their fingers. If they are asked who told them all these things, they reply: Our fathers told us this. As proof they offer the whale bones, which actually are found in large numbers on all the volcanoes.Stepan Krasheninnikov was a member of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, led by Vitus Bering and sponsored by the Russian government, which aimed to survey the resources of Russia's possessions in its far northeast, including parts of what is now Alaska, at a time when those regions were all but unknown to science. The Steller mentioned above was the naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, another notable participant in the expedition (and namesake of the extinct Steller's sea cow).

Explorations of Kamchatka 1735-1741, translation by E. A. P. Crownhart-Vaughan (Oregon Historical Society, 1972). I have modernized the spelling of one word.

Krasheninnikov's account probably should be better known; he was a pioneering geographer and a capable and relatively unprejudiced anthropologist. Though he was sometimes wrong, as in firmly declaring that whales were fish, there is much of value in his account, which is out of print but not that hard to find. The Oregon Historical Society edition (the only complete English-language version) could have used more explanatory notes but is otherwise a noble undertaking.

Image Credit: "The Volcano of Awatcha (Avacha) in Kamchatka, Siberia." Etching with engraving, from the Wellcome Collection. A different engraving of the same image is reproduced in Explorations of Kamchatka.

Labels:

Exploration

Monday, December 13, 2021

Buffon's Ounce, the lonza leggera, and The Long Walk

Slawomir Rawicz was a Polish military officer in World War II who in the 1950s dictated to a ghost-writer a stirring account of how he and several companions engineered their escape from a Siberian prison camp, crossed the Gobi Desert, and then trekked over the Himalayas to safety in British India. Among the incidents he related was a close encounter with two Abominable Snowmen. Just by itself that latter claim might have raised eyebrows, and in fact the consensus now is that Rawicz's account, which was published in 1956 as The Long Walk, celebrated for decades as both an adventure yarn and an anti-Soviet testimony, and eventually filmed (as The Way Back) by Peter Weir, is essentially fictional. Still, at least it makes a good story.

I'm not the only one who has noted the likely influence of Rawicz's book on Harry Mathews's novel Tlooth, which came out in book form in 1966 after having been serialized in the Paris Review. Tlooth, like The Long Walk, describes a clever escape from Siberia and a southward journey over the Himalayas. (It differs from the earlier book in involving, among other things, dental malpractice, obscure religious denominations, and an exploding baseball.) There are no yetis in Mathews's book, but there is a cryptic if not cryptozoological sighting in a chapter entitled "Buffon's Ounce." The narrator and his companions reach a high pass:

But there's one more weird twist to this convoluted story. Tlooth was published, as I said, in the Paris Review. Its author jokingly claimed that he was often mistakenly assumed to have been in the CIA, and even wrote a novel (My Life in CIA) based on that premise. One reason that Mathews might have plausibly been assumed to have been in the CIA was his connection with the Paris Review, one of whose co-founders, the writer Peter Matthiessen, later admitted that he had used the magazine as cover for his CIA work. In 1979 Matthiessen would win the National Book Award for a book about his travels in the Himalayas. Its title was The Snow Leopard.

* And thus a tale for another time: Jefferson's obsession with the remains of the extinct American mastodon, Charles Willson Peale's excavation of a specimen of the same, Peale's painting of his excavation, an album called Kew. Rhone inspired by the painting, a book, celebrating the album, that includes a contribution by Harry Mathews...

I'm not the only one who has noted the likely influence of Rawicz's book on Harry Mathews's novel Tlooth, which came out in book form in 1966 after having been serialized in the Paris Review. Tlooth, like The Long Walk, describes a clever escape from Siberia and a southward journey over the Himalayas. (It differs from the earlier book in involving, among other things, dental malpractice, obscure religious denominations, and an exploding baseball.) There are no yetis in Mathews's book, but there is a cryptic if not cryptozoological sighting in a chapter entitled "Buffon's Ounce." The narrator and his companions reach a high pass:

There, in midafternoon, a shout stopped us.That's the last we hear of the animal. The Italian line is from the first canto of the Inferno, where Dante is brought up short by three beasts, the third of which is "a lithe and very swift leopard" — except that what Dante actually meant by lonza has been long debated. Which brings us to the meaning, otherwise unexplained, of the title of the chapter. "Buffon" is Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, a French naturalist known, among other things, for disparaging the animals of the New World as being inferior to those of the Old (to the fury of Jefferson*), and "ounce" (or in French, "once") is an obsolete word for a large wild feline, based on an etymological misunderstanding of a derivitive of the Latin word "lynx." (A form like "lonza" was misinterpreted as "l'onza.) What Buffon described — he was the first Westerner to do so — was in fact the snow leopard, shown above in an 18th-century engraving based on his work.

"Look!" Beverley pointed uphill.

I saw a pale spotted creature clamber catfashion over snows into the rocks.

Robin remarked, "Una lonza leggiera e presta molto."

But there's one more weird twist to this convoluted story. Tlooth was published, as I said, in the Paris Review. Its author jokingly claimed that he was often mistakenly assumed to have been in the CIA, and even wrote a novel (My Life in CIA) based on that premise. One reason that Mathews might have plausibly been assumed to have been in the CIA was his connection with the Paris Review, one of whose co-founders, the writer Peter Matthiessen, later admitted that he had used the magazine as cover for his CIA work. In 1979 Matthiessen would win the National Book Award for a book about his travels in the Himalayas. Its title was The Snow Leopard.

* And thus a tale for another time: Jefferson's obsession with the remains of the extinct American mastodon, Charles Willson Peale's excavation of a specimen of the same, Peale's painting of his excavation, an album called Kew. Rhone inspired by the painting, a book, celebrating the album, that includes a contribution by Harry Mathews...

Labels:

Harry Mathews

Wednesday, December 08, 2021

Purgatorio

I'm walking in the woods at night in the company of Willie McTell. I see three deer standing a few yards away; somehow, in spite of his blindness, McTell is aware of their presence and able to describe them to me. What he doesn't realize is that a half-grown mountain lion has stepped out from among them and begun to approach us.

We climb a series of concrete steps that ascend to an unseen waterfall somewhere ahead. Far below, on the right, is a broad expanse of seething whitewater. The cat is hard on our heels now, drawn by the smell of the sausages I'm carrying wrapped up in deli paper. McTell knows he's there but doesn't seem overly alarmed, and refers to him, jokingly, as "Kitty." Behind us, silently, the mountain lion's parents have begun to follow.

As we climb, the cats press closer and closer to us, bumping us and sniffing at our hands. One opens its mouth tentatively, but for now doesn't bite down. In desperation I unwrap the sausages and drop one on the steps behind us; it rolls off and into the torrent below. The adult male instantly leaps the railing and lands safely on a rock. We leave it behind and continue to climb. I drop the sausages one by one until we're alone. I know that McTell will be disappointed later about losing the sausages, but he'll understand when I explain.

Labels:

Enigmas

Monday, December 06, 2021

Monday afternoon

I stepped into a little café that was simply a small room with a counter in the rear and a table on either side of the door. The woman behind the counter gestured for me to sit and brought me a menu, which listed just two or three choices. I ordered tea and a pear torte, which turned out to be a delicious warm mélange of fruit and cream swathed in puff pastry, and which was accompanied, for some reason, by a ficelle in a wax bag. When the bill came I was a bit surprised to see that the total came to $60, but even as I reached for my wallet a man strode out of the kitchen, picked up the bill, looked at it, frowned, then began a heated argument with the woman that I couldn't follow, as it was conducted in a language I couldn't identify. I broke off a piece of the ficelle, which was also quite tasty, and waited for the outcome.

Labels:

Enigmas

Saturday, December 04, 2021

Ambition (II)

Edward Gibbon:

Diocletian, who, from a servile origin, had raised himself to the throne, passed the nine last years of his life in a private condition. Reason had dictated, and content seems to have accompanied, his retreat, in which he enjoyed for a long time the respect of those princes to whom he had resigned the possession of the world. It is seldom that minds long exercised in business have formed any habits of conversing with themselves, and in the loss of power they principally regret the want of occupation. The amusements of letters and of devotion, which afford so many resources in solitude, were incapable of fixing the attention of Diocletian; but he had preserved, or at least he soon recovered, a taste for the most innocent as well as natural pleasures; and his leisure hours were sufficiently employed in building, planting, and gardening. His answer to Maximian is deservedly celebrated. He was solicited by that restless old man to reassume the reins of government and the Imperial purple. He rejected the temptation with a smile of pity, calmly observing that, if he could show Maximian the cabbages which he had planted with his own hands at Salona, he should no longer be urged to relinquish the enjoyment of happiness for the pursuit of power.More "Ambition"

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Saturday, November 27, 2021

A Few "Regrets"

I pulled out this slender letterpress chapbook the other day when I was looking for something else. I had forgotten that I owned it. The cover reads Sonnets Translated from Les Regrets of Joachim du Bellay 1553, the publisher is "the Uphill Press, New York," and the translator (who is also the printer) is identified only as A. H. It bears a date of 1972, and the statement of limitations at the back indicates that one hundred and ten copies were printed. (My copy, number 38, is inscribed to a noted architect and his wife, "in old friendship," but that's a tale for another time.)

It didn't take much to identify the person responsible, an arts administrator and biographer of Woodrow Wilson named August Heckscher. But neither in his 1997 New York Times obituary nor in the Wikipedia article devoted to him is there any hint that he was also an avid amateur printer, translator, and poet (probably in that order of importance). For that information you have to refer to the likes of Joseph Blumenthal, the noted printer and author of Typographic Years: A Printer's Journey through a Half-Century 1925-1975 who has this to say:

The brief "Note" attached to this chapbook sets the scene:

Among his public activities, Heckscher was Consultant in the Arts for President Kennedy and a Commissioner of Parks who planted thousands of trees in New York City. In his living room in New York, he set type by hand and printed fine small books and ephemera, often with the help of his son Charles. More recently he has set up "The Printing Office at High Loft" at his summer home in Seal Harbor, Maine, where with young apprentices he prints and publishes modestly but with éclat.A little more digging turned up this photo of Heckscher and his sons at work from a 1962 profile in Life magazine. Letterpress printing was probably never a particularly common hobby, but it did have its aficionados in postwar America, many of whom had day jobs in unrelated fields and carried out a collegial kind of artistic underground in their off-hours. (Broadcaster Ben Grauer, proprietor of the Between Hours Press, was a notable example.) It was negligible from an economic standpoint (hobby printers were careful not to take business away from professionals, and generally their productions were simply given away to friends), but here and there, on presses tucked away in Manhattan apartments or the basements of suburban homes, some fine work was done — and no doubt there are still people doing it.

The brief "Note" attached to this chapbook sets the scene:

Joachim du Bellay journeyed to Rome in 1553 in the service of his uncle, Cardinal du Bellay. The young Renaissance poet and scholar might have been expected to find many rewards during his three years at the center of the classical world. On the contrary, he was extremely unhappy — though it must be remarked that like many who are unhappy when they travel, he was hardly less so when he returned home. In Les Regrets, published in 1558, he poured out in sonnet form the varied pains of exile.Heckscher tells us that he was inspired to translate the selections while he himself was traveling, in his case in Morocco. Below is a sample; I've cropped the page for the sake of readability on the web. Heckscher's margins are more generous, and of course he would have taken pride in his page design. The chapbook is rounded off with an Envoi "from a different hand," that is, from A. H. himself:

Sleep, du Bellay, sleep sound and do not fret.

Dislikes and troubles vanish with the past.

The stuffy Roman dames, the Latin cast,

Are one with centuries that rise and set.

The endless littleness of your regret,

The heart in servitude, the soul harassed,

Are eased by kindly death, which gives at last

The peace men seek in life, but do not get.

Your verses still are read: along the Quai

When earliest Paris spring was on its way

And pear-trees flower'd in your beloved Anjou

I bought your book. I heard from far away,

Above the crimes and passions of our day,

Your sad, so human accents speaking through.

Labels:

Letterpress,

Poetry,

Printing,

Translation

Sunday, October 31, 2021

Notebook: Home Fires

Sir James George Frazer:

Not only among the Celts but throughout Europe, Hallowe’en, the night which marks the transition from autumn to winter, seems to have been of old the time of year when the souls of the departed were supposed to revisit their old homes in order to warm themselves by the fire and to comfort themselves with the good cheer provided for them in the kitchen or the parlour by their affectionate kinsfolk. It was, perhaps, a natural thought that the approach of winter should drive the poor shivering hungry ghosts from the bare fields and the leafless woodlands to the shelter of the cottage with its familiar fireside. Did not the lowing kine then troop back from the summer pastures in the forests and on the hills to be fed and cared for in the stalls, while the bleak winds whistled among the swaying boughs and the snow-drifts deepened in the hollows? and could the good-man and the good-wife deny to the spirits of their dead the welcome which they gave to the cows?

The Golden Bough

Thursday, October 28, 2021

The Old Country

It's a frightening thought that I've reached an age where there are now books that I first read almost fifty years ago, and I'm not talking about The Cat in the Hat. A case in point is this Signet Classics edition of Turgenev's The Hunting Sketches, which I first read so long ago that I remembered only that it had about as much to do with hunting as Richard Brautigan's Trout Fishing in America had to do with angling. But I did know that I enjoyed it at the time, and some vague recollection of its mood, coupled with a desire for an antidote after suffering through The Idiot, led me back to it.

I had long ago discarded my old copy. There are newer translations that for all I know may be better than Bernard Guilbert Guerney's, but nostalgia drew me back to this edition and I found a second-hand but still sturdy replacement copy easily enough.

The Hunting Sketches was Turgenev's first book, and its narrator, a member of the Russian landed gentry who seems to have unlimited time on his hands, is thought to have much in common with the author. Not much actual hunting takes place, just the odd game bird or two, but the narrator's travels in search of sport lead him to various encounters with the peasants and gentlefolk of the Russian countryside, a cast of characters that, for a Westernized Russian like Turgenev, must have seemed intriguingly exotic. The individual sketches range widely in tone and subject, encompassing "tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral...," and so on. Here and there the descriptive passages get a bit florid (at least in this translation), but overall the tone is dispassionate, even anthropological; at times I was reminded of that other meticulous explorer of foreign lands, Lafcadio Hearn. The most memorable tale is probably "Bezhin Meadow," in which the narrator, having become lost, stumbles onto a night encampment of five adolescent boys, who exchange eerie tales of local ghosts and horrors once they think that the narrator has fallen asleep. It's a wonderful piece of writing.

The book was published in the 1850s, and the Russia it describes has been transformed and transformed again since then, but Turgenev seems like our contemporary, or the kind of contemporary we would have if we deserved him. Within the limits of his class and his background and the inevitable constraints of literary creation he described life as he found it. Naturally the authorities were displeased.

I had long ago discarded my old copy. There are newer translations that for all I know may be better than Bernard Guilbert Guerney's, but nostalgia drew me back to this edition and I found a second-hand but still sturdy replacement copy easily enough.

The Hunting Sketches was Turgenev's first book, and its narrator, a member of the Russian landed gentry who seems to have unlimited time on his hands, is thought to have much in common with the author. Not much actual hunting takes place, just the odd game bird or two, but the narrator's travels in search of sport lead him to various encounters with the peasants and gentlefolk of the Russian countryside, a cast of characters that, for a Westernized Russian like Turgenev, must have seemed intriguingly exotic. The individual sketches range widely in tone and subject, encompassing "tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral...," and so on. Here and there the descriptive passages get a bit florid (at least in this translation), but overall the tone is dispassionate, even anthropological; at times I was reminded of that other meticulous explorer of foreign lands, Lafcadio Hearn. The most memorable tale is probably "Bezhin Meadow," in which the narrator, having become lost, stumbles onto a night encampment of five adolescent boys, who exchange eerie tales of local ghosts and horrors once they think that the narrator has fallen asleep. It's a wonderful piece of writing.

The book was published in the 1850s, and the Russia it describes has been transformed and transformed again since then, but Turgenev seems like our contemporary, or the kind of contemporary we would have if we deserved him. Within the limits of his class and his background and the inevitable constraints of literary creation he described life as he found it. Naturally the authorities were displeased.

*

In addition to extensive work as translator, Bernard Guilbert Guerney, who died in 1979, had a second career as the proprietor of the Blue Faun Bookshop in New York City, which was in existence from 1922 into the '70s. (There is a Walker Evans photograph of the shop's exterior.) He was born near Odessa as Bernard Abramovich Bronstein or Bronshtein, and one source indicates that he may have been related to Trotsky. Walter Goldwater, a fellow bookseller, had this to say of him: He was a great talker and one of the ones who was very resentful about the way things were going: things always used to be better; people are now illiterate; he can't stand people coming in; they don’t know anything, and so on. He was very difficult to do business with, but we got along quite well because we used to talk in Russian or talk about Russia.Vladimir Nabokov called Guerney's translation of Gogol's Dead Souls "an extraordinarily fine piece of work."

Labels:

Turgenev

Thursday, October 21, 2021

Visitors

A posh tour bus pulls up outside our house and discharges a group of North Koreans and American supporters, who barge in through our front door carrying books and brightly-colored papier-mâché animals as gifts. Some of the North Koreans carry automatic weapons; there are also some children. I round everybody up and make them leave, then call the police. The police already know about it; they say the tour bus is going all around the country like that and not to worry. When I look at some paperwork tucked into the books I realize that they were bought from a former employer.

Labels:

Enigmas

Monday, October 04, 2021

Calais

Charles Dickens:

The passengers were landing from the packet on the pier at Calais. A low-lying place and a low-spirited place Calais was, with the tide ebbing out towards low water-mark. There had been no more water on the bar than had sufficed to float the packet in; and now the bar itself, with a shallow break of sea over it, looked like a lazy marine monster just risen to the surface, whose form was indistinctly shown as it lay asleep. The meagre lighthouse all in white, haunting the seaboard as if it were the ghost of an edifice that had once had colour and rotundity, dropped melancholy tears after its late buffeting by the waves. The long rows of gaunt black piles, slimy and wet and weather-worn, with funeral garlands of seaweed twisted about them by the late tide, might have represented an unsightly marine cemetery. Every wave-dashed, storm-beaten object, was so low and so little, under the broad grey sky, in the noise of the wind and sea, and before the curling lines of surf, making at it ferociously, that the wonder was there was any Calais left, and that its low gates and low wall and low roofs and low ditches and low sand-hills and low ramparts and flat streets, had not yielded long ago to the undermining and besieging sea, like the fortifications children make on the sea-shore.

Little Dorrit

Wednesday, September 15, 2021

Report of the Committee on Agriculture (II)

Most of this year's butternut squash crop has now been harvested. I grew two types, both of which are hybrids. The tan ones shown above are a variety called Canesi; the others, which can be either mottled green or a two-tone combination of mottled green and yellow-orange, are Autumn's Choice. The colors on the latter variety tend to fade eventually after they're picked.

I planted three or four hills in an area of our yard that hadn't been used for growing anything but grass and weeds for some time. When I dug into it I discovered old cinders, broken glass, and other indications that it had formerly been a household dump, perhaps a century ago, but the soil was apparently suitable for vegetables. About ten or twelve vines emerged, and although at first they were slow to develop once they got going they were quite rampant. The dreaded squash vine borers that are endemic in our area either let them be or did minimal damage; butternuts, which are Cucurbita moschata, are less affected than other squash species. A deer made it over our fence one evening and did some minor damage, but once the fruits themselves started to develop I swathed them in row cover every night and that proved successful. There are still a few squash on the vines but all in all we'll have a good eighty pounds or so of winter squash, which should keep us well supplied with pumpkin pies and side dishes throughout the winter. (Butternuts store for months.) We've shared a few with neighbors already and may wind up giving away more.

I have a few packaged seeds left of both varieties. Since they're hybrids and won't "breed true" there's no point in saving seed from this year's harvest, and Autumn's Choice is becoming hard to find, so next year may be the last for that one. The average size of the squash I harvested this year was in the range of five to seven pounds, which is a bit on the large side to be practical for a small household, so I'll probably mix in a smaller variety next year, perhaps one that is "open pollinated" and can be saved from each year's harvest.

Autumn's Choice proved delicious in previous years, but I won't know about Canesi until they have a chance to cure for a few weeks. Certainly they look appetizing.

I planted three or four hills in an area of our yard that hadn't been used for growing anything but grass and weeds for some time. When I dug into it I discovered old cinders, broken glass, and other indications that it had formerly been a household dump, perhaps a century ago, but the soil was apparently suitable for vegetables. About ten or twelve vines emerged, and although at first they were slow to develop once they got going they were quite rampant. The dreaded squash vine borers that are endemic in our area either let them be or did minimal damage; butternuts, which are Cucurbita moschata, are less affected than other squash species. A deer made it over our fence one evening and did some minor damage, but once the fruits themselves started to develop I swathed them in row cover every night and that proved successful. There are still a few squash on the vines but all in all we'll have a good eighty pounds or so of winter squash, which should keep us well supplied with pumpkin pies and side dishes throughout the winter. (Butternuts store for months.) We've shared a few with neighbors already and may wind up giving away more.

I have a few packaged seeds left of both varieties. Since they're hybrids and won't "breed true" there's no point in saving seed from this year's harvest, and Autumn's Choice is becoming hard to find, so next year may be the last for that one. The average size of the squash I harvested this year was in the range of five to seven pounds, which is a bit on the large side to be practical for a small household, so I'll probably mix in a smaller variety next year, perhaps one that is "open pollinated" and can be saved from each year's harvest.

Autumn's Choice proved delicious in previous years, but I won't know about Canesi until they have a chance to cure for a few weeks. Certainly they look appetizing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)