Sunday, June 16, 2019

Stephen O. Saxe (1930-2019)

The printing historian Stephen O. Saxe died on April 27th of this year, according to a memorial notice in the New York Times today (June 16th) and a brief note from the American Printing History Association, of which he was a founder. Saxe followed an interesting career path that led him from Yale Drama School to television set design to book design at Harcourt, Brace, but it was for his activities as an amateur (in the best etymological sense of the word) that he is best known, at least among printing scholars and enthusiasts. Among his publications was the book pictured above, the definitive study of the 19th-century iron presses that were the first major revolution in printing technology after Gutenberg. (Appropriately, the book was first published in a letterpress edition by Yellow Barn Press, though a trade edition followed.)

I met Stephen Saxe once. I had written to him with a couple of questions about some research I was doing and he generously invited me — a stranger and total novice to the field — and a printmaking friend to his home in White Plains, where he spent a couple of hours showing us his printing equipment and some treasures from his library, including an extraordinary 19th-century French specimen book filled with elaborate typographical decorations. (The APHA announcement has a nice photo of Saxe at his home.) There aren't many of his kind still around.

Update: Amelia Hugill-Fontanel has written a longer appreciation for the APHA website: "Stephen O. Saxe, A Partner in Printing History, (1930–2019)."

Labels:

Letterpress,

Printing

Monday, June 10, 2019

Mistaken Identity

An incident that Julio Cortázar (a noted admirer of Verne) would no doubt have appreciated, as related by Alejandro Zambla:

I remember how at sixteen, I convinced my dad to give me the six thousand pesos that Hopscotch cost, explaining that the book was "several books, but two in particular,"* so that buying it was like buying two novels for three thousand pesos each, or even four books for fifteen hundred pesos each. I also remember the employee at the Ateneo bookshop who, when I was looking for Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, explained to me patiently, over and over, that the book was called Around the World in Eighty Days and that the author was Jules Verne, not Julio Cortázar."Bring Back Cortázar," from The Paris Review (online) October 17, 2018.

I can sympathize, though, with the poor bookseller, who was no doubt used to dealing with cronopios like this fellow (played by Marty Feldman):

* The phrase is borrowed from the "Table of Instructions" of Hopscotch.

Sunday, June 02, 2019

Monday, May 13, 2019

"Mala Cosa" (Cabeza de Vaca)

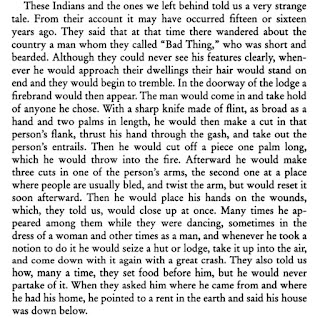

The Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca recounts an incident that was related to him by Native Americans he encountered during his long sojourn across the southern US and northern Mexico:

Narrative of the Narváez Expedition, edited by Harold Augenbraum.

Cabeza de Vaca was one of a handful of survivors of a 16th-century expedition to Florida that went catastrophically wrong. The accuracy of his account of his travels on many points has been questioned, but few things in it are as difficult to believe as the one thing that is unquestionably true, which is that he and three other men did survive eight years wandering among various Native American peoples before finally meeting up with a group of his countrymen near Culiacán in Sinaloa. Along the way he found himself cast in the role of faith healer, and claimed to have performed countless miracles on ailing (and very grateful) Indians.

The passage above has been much pondered. It appears to record some kind of shamanic performance reminiscent in some ways of modern "psychic surgery" cons and fortune-telling bujo scams. How the Indians understood what they told Cabeza de Vaca, and how it differed from what he recorded, is impossible to say. It's the oddest passage in the book.

Labels:

Cabeza de Vaca,

Enigmas,

Mexico,

Notes

Ouch

Jeopardy clue: "John & Priscilla Alden lie in the U.S.A.'s oldest maintained cemetery, which like a poem about the couple, is named for this person." Contestants' proposed questions: "Who is Poe?," "Who is Arlington?," and "Who is Mary?"

(The correct question: "Who is Myles Standish?")

Labels:

Amusements,

Jeopardy

Sunday, May 12, 2019

On Ants (Thomas Bewick)

"The history and œconomy of these vary curious Insects are (I think) not well known — they appear to manage all their Affairs, with as much forethought & greater industry than Mankind — but to what degree their reasoning & instructive powers extend is yet a mystery — After they have spent a certain time toiling on earth, they then change this abode, get Wings, & soar aloft into the atmosphere — It is not well known what state they undergo, before they assume this new character, nor what becomes of them after."

(Memoirs)

On Being Alone

"As the lodges afforded so little shelter, people began to die, and five Christians quartered on the coast were driven to such extremity that they ate each other until but one remained, who, being left alone, had nobody to eat him." — Cabeza de Vaca

Adapted from the Lakeside Press edition of Narrative of the Narváez Expedition, edited by Harold Augenbraum.

Labels:

Cabeza de Vaca,

Notes

Friday, May 03, 2019

An Existential Necessity (Luc Sante)

The Paris Review has inaugurated a new blog, Pinakothek. Written by Luc Sante, it's devoted to "miscellaneous visual strata of the past." Here's an excerpt from the second post, "Arcade":

Getting yourself photographed was a pastime and an existential necessity. It reminded you that you existed outside your own head. It showed you your face as others would see it. It gave you an opportunity to compose yourself, although few had the skill to do so successfully, and often the photographer’s haste and hard sell would mitigate against it. Most people come off in arcade pictures as if they had suddenly been shoved onstage to face an audience of thousands."Pinakothek" (from a Greek and Latin word for a picture gallery) was also the title of a short-lived feature that Sante maintained on his website a number of years ago.

Labels:

Luc Sante,

Photography

Wednesday, May 01, 2019

Hera

Her sons are out of college and living lives of their own by the time her husband leaves. She could stay on in the house but every room has bad memories, so she winds things up and moves back to the river town where she was born. It's the same river but the people have moved on. Old acquaintances, when she happens to bump into someone she recognizes, are pleasant enough but their faces are burdened with histories she no longer shares. Downtown there are newcomers, refugees from a faraway war that has disappeared from the headlines. She rather likes the women, who are friendly, direct, and tough, but finds the men a harder read. She volunteers a bit and joins a gym, and keeps the few grey-haired men who seem to sense an opportunity at arm's length.

On overcast days she likes to walk through town and over the bridge and watch fishermen drop their lines into the dark water. Sometimes the drawbridge rises and a barge goes by, its wake slowly rippling until it breaks on the shore. She wonders what the barges carry and where they are bound, upriver empty and downriver full. Semis cross the bridge and sometimes sound their horns at her; she thinks they wouldn't bother if they could see the lines in her face.

The mail brings letters, catalogs, bills. She keeps her rooms tidy, cooks casseroles that last for days, reads into the night, rises with the dawn. Sometimes she sees great flocks high above and hears the faint cries of birds returning to Canada for the summer. She resolves to make the same trip some spring, when the moment is ripe and the last ice floes have broken up.

Labels:

Migrations

Monday, April 08, 2019

Notes for a Commonplace Book (24): Temporary Separateness

Alice Munro:

This lucky woman, Joan, with her job and her lover and her striking looks—more remarked upon now than ever before in her life (she is as thin as she was at fourteen and has a wing, a foxtail of silver white in her very short hair)—is aware of a new danger, a threat she could not have imagined when she was younger. She couldn't have imagined it even if somebody had described it to her. And it's hard to describe. The threat is of change, but it's not the sort of change one has been warned about. It's just this—that suddenly, without warning, Joan is apt to think: Rubble. Rubble. You can look down a street, and you can see the shadows, the light, the brick walls, the truck parked under a tree, the dog lying on the sidewalk, the dark summer awning, or the grayed snowdrift—you can see all these things in their temporary separateness, all connected underneath in such a troubling, satisfying, necessary, indescribable way. Or you can see rubble. Passing states, a useless variety of passing states. Rubble."Oh, What Avails," from Friend of My Youth

Labels:

Alice Munro,

Notes

Thursday, April 04, 2019

Music Notes: "Idumea"

Charles Wesley, one of the founding fathers of Methodism, is said to have penned some 6,500 hymns, among them "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing." I can't say for sure — not having heard them all — but I suspect he never wrote another as weirdly beautiful as "Idumea":

And am I born to die?The peculiarities begin with the title itself, which seems to have come not from Wesley but from a later arranger. Why "Idumea"? According to reference works, Idumea (or Edom) was an ancient kingdom south of the Dead Sea. It is mentioned in the Bible, though not, as far as I can tell (and I'd welcome an exegesis) in any context that would explain the lyrics above. The noted folklorist A. L. Lloyd, in his liner notes to the version of the song performed by the English folk group the Watersons, thought it unnecessary (or was it impossible?) to explain the allusion.

To lay this body down

And as my trembling spirit fly

Into a world unknown?

A land of deepest shade

Unpierced by human thought

The dreary region of the dead

Where all things are forgot

Soon as from earth I go

What will become of me?

Eternal happiness or woe

Must then my fortune be

Waked by the trumpet's sound

I from my grave shall rise

And see the judge with glory crowned

And see the flaming skies

Then there's the way the song begins: in mid-sentence, in mid-thought. Hymns tend to speak in a collective voice; this one is first-person singular and sounds almost like a monologue spoken in character, along the lines of Spoon River Anthology. Even the hymn's theology seems a tad unorthodox. Christianity, as a religion that offers, in effect, a choice of afterlives, has long alternated in its vernacular forms between a kind of "Joy to the World / God is Love" cheeriness and a darker strain, whether expressed in threats of hellfire and brimstone or in the death-obsessed pessimism of the danse macabre and Blind Willie Johnson's "You Gonna Need Somebody on Your Bond." But Wesley's description of

The dreary region of the deadsounds more like the pagan, antinomian conception of the underworld (peopled by Homer's "exhausted dead") than it does the Christian vision of a place where sinners are sent to be paid back for their misdeeds. Is this because the speaker's voice is supposed to be an ancient, Idumean one? Is it because Wesley, though an evangelist and missionary, was also a classically educated scholar for whom the tropes of Greek and Roman literature would have been part of his intellectual training? Or was Wesley, good Methodist, really a secret Modernist avant la lettre (Pound's Cantos, after all, also begins with "And …")? All the elements are there: cryptic reference to antiquity, fragmented monologue …

Where all things are forgot

According to Lloyd, the hymn fell out of favor in England, but remained popular among parishioners in what he calls "remoter settlements of the Upland Southern states of America." One can only wonder what they made of it.

The above note was originally published in A Common Reader's blog Book Case in 2003. I have dusted it off and revised a few points.

Labels:

Missionaries,

Music,

Watersons

Friday, March 22, 2019

Customer Service Wolf

Three installments from Anne Barnetson's droll comic about the adventures of a lupine bookshop clerk. Having served in that role for many years in an earlier phase of my life I can vouch for its essential accuracy.

Labels:

Bookselling,

Comics

Sunday, March 10, 2019

Berlin (Jason Lutes)

Two brilliant pages from Jason Lutes's mammoth graphic novel set in the waning years of the Weimar Republic.

Berlin is published by Drawn & Quarterly.

Labels:

Art,

City,

Graphic novels,

Illustration,

Jason Lutes,

Novels

Sunday, February 24, 2019

The Fear

Ruth Otis Sawtell & Ida Treat:

Our greatest adventure we found at Mérigon. Mérigon, with its face to the sunny roadside and its back to the dark gorge where the Volp rushes past the Plantaurel, has been the haunt of something wild and sinister. The peasants called it la Peur, the Fear. All one summer it blasted the valley. Crops drooped, cattle died. There were cries in the night, whirring of wings where no birds flew. At last the men of Mérigon set out to hunt la Peur. Guns in hand they scoured the fields, the river, the rocks, until some one—with a silver bullet—shot it down. He brought back no trophy, only the vague word of having killed "something like a bird," but from that moment the blight was lifted from the countryside. To-day you can not find a man in Mérigon who will admit participating in that hunt. But there is something in the atmosphere of the valley suggesting that if la Peur should rise again, there would still be men to hear the flutter of its wings.

—Primitive Hearths in the Pyrenees

Thursday, February 21, 2019

Compliments of the Dead

This appealing book is the product of two American women, Ruth Otis Sawtell (1895-1978), a noted anthropologist and academic (and, later, author of mystery novels), and Ida Treat (1899-1978), who was, among other things, a journalist, academic, and New Yorker contributor in the Shawn era. There couldn't have been many American women engaged in the serious study of the European Paleolithic during the Roaring Twenties, but there certainly were two, and their account of their caving adventures and fieldwork, though obscure now, is more substantial than the typical Americans-abroad fare of the day. It was handsomely produced by D. Appleton & Co. with lots of drawings* and photos of artifacts and cave art and a gold-stamped front cover (at least in my copy — there seems to be a variant with a plain red binding). It's out of date now (even the famous paintings of Lascaux were unknown when they wrote it), but still enjoyable.

My copy, which I bought at one book sale or another years ago, came with the business card shown below paper-clipped to the title page. Francis G. Wickware was an editor at Appleton, and may well have been the editor of the book (he had a background in geology and was probably of a scientific bent). If the book was a gift from him the circumstances are somewhat puzzling, as "the late" has been scrawled above his name. Primitive Hearths in the Pyrenees was published in 1927, thirteen years before Wickware's death; perhaps just before he died he set a copy aside for someone he knew would be interested.

* The drawings were executed by Paul Vaillant-Couturier, one of the founders of the French Communist Party. He was married to Ida Treat at the time (they later divorced) and participated in the fieldwork.

Update: Below is the cover art for one of Ruth Sawtell Wallis's mystery novels. I suspect that this is not how she actually dressed during her excavations.

Labels:

Paleontology

Monday, February 11, 2019

The Memory Man

These three slender books by the Guatemalan Jewish writer Eduardo Halfon are published by Libros del Asteroide, a Barcelona-based company that publishes a wide range of modern literature, all in the same attractive format. Two of the three, or more accurately two and a half of the three, have been published in English translations by Bellevue Literary Press, along with another Halfon book (which I haven't read) entitled The Polish Boxer.

Each book succeeds as an individual work, but they're also part of a larger whole in which characters and events may be alluded to in one but more fully developed in another. Halfon, who spent part of his childhood in the US and is bilingual (though he doesn't do his own translations), has underlined the fluidity of his project by lifting sections of Signor Hoffman and combining them with the contents of Duelo for the US translation.

All three are narrated by someone named Eduard Halfon who is a Jewish-Guatemalan writer exploring the details and consequences of his personal and family history (but who should nevertheless not be confused with the author). Imagined events aren't necessarily deprecated in favor of real ones; thus Duelo (a title that can mean both "mourning" and "duel") centers around a half-remembered story about an uncle who drowned as a child in Lake Amatitlán. The fact that the drowning never happened both is and isn't less important than the ways it is (mis)remembered. The narrative begins in Guatemala but eventually travels to Florida and Germany (and to Italy and Poland in the English version).

The books have an understated force that becomes cumulative when they are read together (in whatever arrangement or order). Halfon doesn't bludgeon the reader, even when he deals with weighty matters (the Holocaust is a shadow over the entire enterprise), but instead prefers to work by indirection. His books echo each other but they also reverberate across entire fields of history.

Labels:

Eduardo Halfon,

Guatemala,

Jewish

Wednesday, February 06, 2019

Roma: Words Unspoken

I had been looking forward to seeing Alfonso Cuarón's Roma as soon as it made it to a local theatre, and it didn't disappoint. I'm not a movie critic and won't attempt a synopsis or analysis of the film*, but in a very quick summation it's about a few months in the lives of a well-to-do (but perhaps downwardly-mobile) Mexico City household around 1971. (Cuarón drew on his own family memories, and he has meticulously — even obsessively — recreated the texture of the world he grew up in.) At one crucial point the family's story intersects dramatically with the tumultuous course of the broader history of twentieth-century Mexico. The film is beautifully designed, acted, and shot (in black and white), and has the sweep and richness of a great novel. I'll be watching it again.

Pictured above is Cleodegaria (played by newcomer Yalitza Aparicio), one of the family's Oaxacan servants and the film's emotional center. One criticism that has been leveled at the film is that we don't really get to learn much about what she thinks and feels, but I think that apparent silence is itself the point. (As it happens, I think we can get a fair idea of what she thinks and feels, but to do so requires attention to more than words.) Roma isn't your typical Hollywood have-it-both-ways movie in which all conflicts are resolved and all the characters overcome the limits of their personal histories, their class or racial backgrounds, and are at last fully revealed as equal agents. Being constrained and unheard is part of the social reality of Cleo's life (as it is, in different ways and degrees, of the lives of the family she serves); for a director to pretend otherwise would be a betrayal.

* For a full and thoughtful review, Alma Guillermoprieto's NYRB review, "The Twisting Nature of Love" is a good place to start.

Wednesday, January 23, 2019

Owl

Winter can be a frustrating time for the saunterer, but now and then you get a lucky break. On a mild Sunday afternoon in January I put the dog in the car and drove a few miles to a park where there are four thousand or so acres of woodlands and fields. The park road up the hill I wanted to visit was closed, so I left the car at the bottom and took a trail that hooked around to the top. The trail was deserted and the woods silent except for the occasional sound of a jet passing overhead. At the summit, stone camping shelters stood empty and alone among unmown fields and scattered oaks, their fires cold, but solitary electric lights burned, even in daylight, to mark the entrances to the rest rooms. On our way back down I heard an owl hoot several times in quick succession not far off in a stand of pines, but I never spotted it. As we drove out a hawk crossed in front of us and alit in a tree. I pulled over but I knew it would fly off if I opened the car door and so made no attempt to get a better look.

On the way home I decided to turn onto a back road I don't usually take. I saw a jogger up ahead of me on the left, and as I slowed I noticed something in the neglected field on my right: a barred owl, perched on a dead tree. I pulled over, turned on the four-way flashers, reached for my camera, and rolled down the window.

I see owls with some regularity, sometimes by accident and sometimes by intention, but most often by having the intention of seeing them by accident. Contrary to the assumptions many people have, they're not necessarily exclusively nocturnal, and barred owls, which are frequently active by day, aren't particularly skittish. Still, I've never had one pose so cooperatively, at eye level just a few yards off and in decent light.

Fortunately, the dog, who barks or howls at anything from squirrels to Canada geese, either didn't see it or didn't register it as potential prey. He no doubt wondered why we had stopped. I took pictures for several minutes, while the owl kept an eye on the field and now and then swiveled its head to regard me with apparent neutrality. I kept expecting it to fly off but it never did. Eventually it was I who drove away instead.

Labels:

Natural history,

Owl,

Walking

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

Measureless Nights

Winter mornings, waiting for dawn. (But then with the streetlight right outside the window it's never truly dark.)

John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts: "An ocean without its unnamed monsters would be like a completely dreamless sleep." They had mariners in mind but they could easily have reversed the simile. A dreamless, utilitarian sleep is like a disenchanted sea. Nothing emerges from it that we don't already know.

Or we dream but remember nothing, our dream-selves wandering off through rooms we will never see. Borges, on the philosophers of Tlön, who held that "While we sleep here, we are awake elsewhere and in this way every man is two men." He might have added, "or none."

Labels:

Night pieces,

Notes

Saturday, January 12, 2019

Thaw

A scene from Paweł Pawlikowski's Cold War, the follow-up to his Oscar-winning Ida from five years ago, which was one of my favorite movies of the last twenty years. I'd rate Cold War one notch below the earlier film, mostly for some choppiness in the latter half and an ending I didn't much care for, but it's still a very consequential movie (and with some of the same cast members, notably Joanna Kulig, who had a cameo in Ida but utterly dominates here). And of course it's in black and white, as all films worth watching should be. (I'm exaggerating, of course, a little.)

Cold War is about various things but the action principally concerns music makers making various kinds of music, and there's an almost programmatic sequence, from a bagpiper at the film's opening who's playing sounds that could be a thousand years old to more recent folk and classical music to jazz and kitsch and Bill Haley and the Comets (heard above). All of the music, as far as I could tell, is diagetic (that is, it's either being performed as part of the action or is listened to by the characters) except for the Goldberg Variations accompanying the credits.

Claire Messud has a thoughtful appraisal in the New York Review and Lisa Liebman at Vulture has a good article on the music in the film.

Labels:

Film,

Paweł Pawlikowski,

Poland

Monday, December 31, 2018

Monday, December 17, 2018

Season's Greetings

Art by Tom Gauld. Hat tip to Tororo.

Update: A memorial notice published in the New York Times on December 23, 2018, may contain a reference to Beckett's Endgame. Addressing herself to "My darling Alvin," the writer declares, "I celebrate the years of our connection and all that you taught me about life, on and off the stage. No one with whom I'd rather have shared a trash can."

Thursday, December 13, 2018

Destinies

Vera Brittain:

When I was a girl at St. Monica's and in Buxton, I imagined that life was individual, one's one affair; that the events happening in the world outside were important enough in their own way, but were personally quite irrelevant. Now, like the rest of my generation, I have had to learn again and again the terrible truth of George Eliot's words about the invasion of personal preoccupations by the larger destinies of mankind, and at last to recognize that no life is really private, or isolated, or self-sufficient. People's lives were entirely their own, perhaps — and more justifiably — when the world seemed enormous, and all its comings and goings were slow and deliberate. But this is so no longer, and never will be again, since man's inventions have eliminated so much of distance and time; for better, for worse, we are now each of us part of the surge and swell of great economic and political movements, and whatever we do, as individuals or as nations, deeply affects everyone else. We were bound up together like this before we realized it; if only the comfortable prosperity of the Victorian age hadn't lulled us into a false conviction of individual security and made us believe that what was going on outside our homes didn't matter to us, the Great War might never have happened.Testament of Youth (1933)

Labels:

Notes,

World War I

Sunday, December 02, 2018

Intruders

For a couple of years when I was a kid my father and I used to traipse through the woods on what had once been farmland, looking for old foundations that might indicate a household dump somewhere not far off, where, if we were lucky and dug carefully with a trowel or a shovel, we might find patent medicine bottles in amber or cobalt blue, or maybe even a handblown flask whose glass would be flecked with bubbles of nineteenth-century air. If we were on water supply property we'd bring our fishing rods for cover — angling was permitted, trespassing was not — but as far as I remember no one ever called us on it, and encounters with anyone else in those woods would have been few and far between. Now and then we'd find a ruined building that was still standing, surrounded by vegetation, its insulation mixed with mouse nests and its shingles decaying, but those were too new to bother with, offering nothing but beer cans and waterlogged magazines.

My father was a surveyor by profession, and the company that employed him secured a large contract for laying out lots on a tract of a thousand acres or so that had been purchased for development. Most of it was second growth woodland, hilly and criss-crossed with stone walls, but there was also a low area that still served to grow corn up until the time the developers started work. There was an abandoned house still standing on the property, and under the pretext of reconnoitering for purposes of the survey we went one day to take a look around. I don't remember much about it now except that the building had at least three stories and must have been a comfortable farmhouse a few decades before.

We found a way in and walked the rooms. How many years they'd been unoccupied is hard to say; there was some story about an elderly widow living in a nursing home who had finally died. Certainly there was nothing useful still in the house; whatever furnishings had any value had long been sold or taken away by relatives or just looted, and the only thing I remember with certainty is that there was a cupboard that was still — bizarrely — neatly stocked with glass jars of vichychoisse or borscht. As we were exploring we heard footsteps on the wooden floor and a kind of desperate wail, and after a few seconds a very large and frightened Great Dane appeared. It couldn't have been left behind by the former owner — it had been too long — and no doubt it had found a way in as we had, and maybe couldn't find its way out. My father shooed it away and it disappeared deeper into the house.

We left empty-handed. The house was torn down not long after. There's no trace of it now.

Labels:

Souvenirs

Friday, November 30, 2018

Notes for a Commonplace Book (23)

Charles Morgan:

In each instant of their lives men die to that instant. It is not time that passes away from them, but they who recede from the constancy, from the immutability of time, so that when afterwards they look back upon themselves it is not themselves they see, not even—as it is customary to say—themselves as they formerly were, but strange ghosts made in their image, with whom they have no communication.From The Fountain, quoted by Vera Brittain in Testament of Youth

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Representative Man

David W. Blight:

Over more than fifty years, 1841-1894, Douglass sat for approximately 160 photographs and wrote some four essays or addresses that were in part about the craft and meaning of pictures. In engravings and lithographs his image graced the pages or cover of all major illustrated papers in England and the United States. His picture was captured in all major forms of photography, from the daguerreotype to stereographs and wet-plate albumen prints. Photographers, some famous and some not, all across the country sought out Douglass for his image. As the historians of his image have shown, the orator performed for the camera. He especially presented himself without props, his own stunning person representing African American "masculinity and citizenship." He helped to choose the frontispieces for his autobiographies, which carried his photograph, and he especially sought to create for a wide audience successive images of the intelligent, dignified black man, and statesmanlike elite, at the same time he understood that photography had evolved into a "democratic art," allowing almost anyone to leave an image for posterity. Visually, by the 1870s and 1880s, Douglass was one of the most recognizable Americans; the dissemination of photographs of him became, therefore, a richly political act.— From Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

Image: Frederick Douglass, from a full-plate daguerreotype in the collection of the Onondaga Historical Association.

Saturday, November 10, 2018

Wednesday, October 31, 2018

Fog

Reservoir views, Halloween morning. The sharp-eyed may notice a passing bird or two in some of the images below.

Labels:

Fog,

Photography

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

Responsibility

Adam Serwer, writing in The Atlantic:

Ordinarily, a politician cannot be held responsible for the actions of a deranged follower. But ordinarily, politicians don’t praise supporters who have mercilessly beaten a Latino man as “very passionate.” Ordinarily, they don’t offer to pay supporters’ legal bills if they assault protesters on the other side. They don’t praise acts of violence against the media. They don’t defend neo-Nazi rioters as “fine people.” They don’t justify sending bombs to their critics by blaming the media for airing criticism. Ordinarily, there is no historic surge in anti-Semitism, much of it targeted at Jewish critics, coinciding with a politician’s rise. And ordinarily, presidents do not blatantly exploit their authority in an effort to terrify white Americans into voting for their party. For the past few decades, most American politicians, Republican and Democrat alike, have been careful not to urge their supporters to take matters into their own hands. Trump did everything he could to fan the flames, and nothing to restrain those who might take him at his word."Trump's Caravan Hysteria Led to This," October 28, 2018

Labels:

Politics

Saturday, October 27, 2018

Enough is Enough

Image credit: The Dallas Holocaust Museum, via the website of Syracuse Cultural Workers, which notes, "This powerful artwork is a signature image of the DHM which hosts thousands of school children each year."

Thursday, October 25, 2018

Monk's Mood

What to listen to when you're out driving before dawn, and the streetlights are lit up because it's never really dark anymore, and the traffic lights aren't working right and already the cars are starting to fill the streets and people are on their way to do things that give them no joy but there's another day to get through, and to hell with the ones getting into their limos who will be rolling the dice for all of us today, because it's Monk, dammit, Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, 1957, and open your ears and show a little respect for once for the things that really matter.

Labels:

Jazz,

John Coltrane,

Music,

Thelonious Monk

Sunday, October 07, 2018

"What Is Jazz?"

The poem below was printed in a local newspaper in 1966. As the name of the poet would mean nothing to anyone who didn't know her personally I choose to keep it private.

What Is Jazz

jazz is America's song

it's freedom

it's bebop and blues

it's bourbon street and harlem

jazz has a pulse

not a beat

(jazz is a live beast

not a metronome)

it skids and slides

it laughs and sobs

jazz can talk

it talks about yesterday and tomorrow

but mostly about today

about right now

about steamy cellars, hot coffee

and that guy sitting next to you

his troubles

his blues

and that girl he loves

jazz is young

it's always the new thing

it's always out

it wanders

alone

it's tough; it's gutsy

jazz is brave

it does what it feels

not what's right

not what's good

jazz is people who are out

people who walk the streets

it doesn't hide

lice on rats

cold-water flats

jazz gets in

it's real

it's dirty

but jazz never lies to you

it tells you when it hates

it tells you when things are rotten

then it throws back its head

and laughs

it says

man, don't let things get you down

relax baby

enjoy yourself

like this, man

then it bops off

and lets off with a good earthy roar

and ya smile and say

hi bud can I buy you a beer?

what is jazz?

jazz is life, fella

jazz is life.

Tuesday, September 18, 2018

Black Wall of Certainty

Amar, a Moroccan adolescent, hides out on the roof while the house he has been staying in is raided by the French, who are looking for members of the Istiqlal, an underground independence movement:

He listened: they were going back down the stairs, back along the galleries, back through the house, and away. They had parked their jeeps somewhere far out in the fields, for he waited an interminable time before he heard the faint sound of doors being shut and motors starting up. When they were gone he turned over and sobbed a few times, whether with relief or loneliness he did not know. Lying up here on the cold concrete roof he felt supremely deserted, exquisitely conscious of his own weakness and insignificance. His gift meant nothing; he was not even sure that he had any gift, or ever had had one. The world was something different from what he had thought it. It had come nearer, but in coming nearer it had grown smaller. As if an enormous piece of the great puzzle had fallen unexpectedly into place, blocking the view of distant, beautiful countrysides which had been there until now, dimly he was aware that when everything had been understood, there would be only the solved puzzle before him, a black wall of certainty. He would know, but nothing would have meaning, because the knowing was itself the meaning; beyond that there was nothing to know.Probably my favorite of Paul Bowles's novels, The Spider's House, which was published in 1955, represents its author's most sustained attempt to depict the interior lives of Moroccans, even if the passage above seems to borrow as much from twentieth-century existentialism as it does from cultural anthropology. Other sections of the book deal, more conventionally, with an expatriate American novelist named John Stenham and a wayward young American woman named Lee Veyron. As the narratives converge, the mutual failure of understanding across cultures comes to the fore. The French colonizers, in the meantime, are depicted as cloddish torturers, while the members of the Istiqlal, who drink alcohol and sport Western clothing, are regarded by Amar (and presumably by Bowles) as corrupt and un-Islamic. Stenham, who speaks Maghrebi Arabic, deplores the encroachments of the modern world into traditional Morocco; Veyron welcomes them.

All of this no doubt reads very differently now than it did when the book was first published; the attempt of an outsider to depict (and thereby define) the consciousness of an inhabitant of a third-world country would probably be regarded as presumptuous if not downright offensive, and Bowles's pessimism about decolonization, like Naipaul's, would be seen as serving the interests of imperialism. But though Stenham seems, on the surface, an obvious stand-in and mouthpiece for Bowles, the writing of fiction exacts its toll on the characters. Stenham is a nostalgist for the primitive, but he is also an insensitive boor who ends by availing himself of his privilege as a Westerner to flee a situation that Amar has no escape from. Bowles the novelist is already a step ahead of his potential critics.

Labels:

Novels,

Paul Bowles

Thursday, September 13, 2018

Monday, September 03, 2018

V is for ...

A case of a ghastly linguistic muddle involving, in one sentence, no fewer than five languages:

Euclides da Cunha, who was a fanatical republican, a man totally convinced of the necessity of the republic in order to modernize Brazil and create social justice in the country ... was working at that time as a journalist in São Paulo and wrote vehement articles against the rebels in the northeast, calling this rebellion "our vendetta" because of the French reactionary movement in Britain against the French Revolution.The passage above is from Mario Vargas Llosa's A Writer's Reality, based on a series of lectures he delivered (in English) at Syracuse University in 1988. The context is a discussion of the Brazilian writer Euclides da Cunha, whose non-fiction work Os Sertões, regarded as one of the foundation stones of his country's literature, describes a millenarian (and, at least in part, monarchist) uprising in Northeast Brazil towards the end of the 19th century. (Vargas Llosa used the same revolt as the basis for his own novel, La guerra del fin del mundo.) But Euclides da Cunha, who wrote in Portuguese, never called the events in Canudos (where the revolt was centered), "our vendetta"; he called them nossa Vendée, that is, "our Vendée," in allusion to the French counterrevolutionary uprising of 1793. Not writing in his native Spanish, Vargas Llosa has mistakenly employed a false English cognate of Italian origin that in fact has no relation to the French word used in the Portuguese text; moreover, he has apparently confused Britain with Brittany, which is at least vaguely in the same part of France as the department of the Vendée.

The moral of the story, perhaps: never be your own translator.

NB: Os Sertões has been translated into English at least twice, once by Samuel Putnam as Rebellion in the Backlands, and in a recent Penguin Classics translation as Backlands: The Canudos Campaign. Vargas Llosa's novel, which has considerable merit of its own, has been translated as The War of the End of the World.

Thursday, August 09, 2018

City

I'm walking the dog home across a city that bears little relation to the real one, as if Robert Moses had succeeded in his nefarious scheme to plow an expressway through lower Manhattan. On a quiet Greenwich Village street I notice a small garden with a few plants and decorations, and I say to myself, "A real hippy must live there." Up ahead, a pickup truck approaches; as it passes I see a young woman standing in the back. She's singing these words:

I'm proud to be a New York City hippyI recognize the song, and the woman is stunned when I join in halfway through. The truck keeps going. There's nothing left for me to do but pick my way east through the cloverleafs and dead ends, heading home.

I'm proud of dirty feet and dirty hair

I'm proud of living with the cock-a-roaches

I'm proud of living in a garbage can*

* Actual song by David Peel, c. 1972.

Labels:

City

Thursday, August 02, 2018

The Impossible Book

The CD insert for a radio play by Peter Belgvad and Iain Chambers, from the limited-edition version of The Peter Blegvad Bandbox. Astute listeners may recognize the voice of the distinguished British actress Harriet Walter in the role of Agatha Christie, as part of a cast that also features XTC founder and longtime Blegvad collaborator Andy Partridge. The insert design and art are by Blegvad.

Labels:

Peter Blegvad

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

Blegvad in a Box

Chris Cutler's ReR Megacorp has just released a snazzy boxed set bringing together the four albums that Peter Blegvad has recorded for the label, packaging them along with a two-CD compilation of live performances, previously unreleased tracks, and "eartoons" entitled It's All 'Experimental,' as well as an attractively designed illustrated 70-page booklet of notes and musings*, and (if you've plumped for the limited edition) an autographed CD of a radio play entitled The Impossible Book.

I came to Blegvad's musical output (he's also a cartoonist and graphic artist) first via Choices Under Pressure, a mostly solo recording from 2001 that I love but that many aficionados are lukewarm about, and then moved on to his fine 1990 Silvertone CD King Strut and Other Stories. The ReR recordings in this Peter Blegvad Bandbox, loosely focused on a core trio of Blegvad, Chris Cutler, and John Greaves, meticulously document one of the most sustained partnerships of his career, and contain much of his best work as well as some material that is perhaps only for the true devotee.

The most recent of the four ReR CDs, Go Figure, was reviewed briefly in this space when it was released last year. Of the other three, Just Woke Up , from 1995, seems the strongest, both musically and lyrically. Hangman's Hill, from 1998, is the weakest (despite the likeable title track), and 1988's Downtime falls somewhere in the middle. (The last features several Blegvad compositions that were originally recorded by Anton Fier's Golden Palominos during Blegvad's association with that shifting ensemble; by and large the Palominos versions are stronger.) The two-disc It's All 'Experimental' is a valuable omnium gatherum featuring, among other things, two versions of "King Strut," two versions of "Shirt and Comb," and a Blegvad-sung rendition of "A Little Something," originally sung by Dagmar Krause when she, Blegvad, and Anthony Moore made up a trio called Slapp Happy.

As for The Impossible Book, it will have to wait until the CD player in my car starts functioning again.

* The designer is Colin Sackett of Uniformbooks, and the booklet includes liner notes and annotations by Blegvad, Chris Cutler, John Greaves, and Karen Mantler, as well as photographs, Blegvad drawings, and whatnot.

Labels:

Music,

Peter Blegvad

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

Life force

Images for a prospective re-reading of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, July 2018.

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils. With an anxiety that almost amounted to agony, I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.

Labels:

Fungi

Wednesday, July 11, 2018

Betrayal

These are not normal circumstances. Nancy LeTourneau:

What we are watching is a complete reorienting of the foreign policy of the United States, and most Republicans are going along because they're too afraid of blow-back from their base. It just so happens that this reorientation is exactly what Vladimir Putin has always wanted. It not only weakens our allies, it weakens us and turns Russia into a player on the global stage. At some point, we all are going to have to recognize that either Trump is a madman swinging wildly in a way that could destroy this country, or he is, as Hillary Clinton once pointed out, a puppet of Putin's. Perhaps some of both."Why Would Trump So Viciously Attack Angela Merkel?," from Washington Monthly.

Our founders attempted to provide us with tools to deal with a situation like this. What they didn't count on was that an entire media apparatus would be developed to enable this kind of madness and that a political party would sit back and watch it happen because they were too drunk with power and/or too cowardly to do anything about it.

It's now sadly impossible to avoid the conclusion that the US president has become, for motives that can be speculated on if not known with certainty, the instrument if not the engineer of a conspiracy designed to destroy liberal democracy. One doesn't need to be a particular admirer of Angela Merkel — or Hillary Clinton, for that matter — to understand that everything we ought to value in common — government by consent of the people, human rights, equal treatment under the law, compassion, reason, our own future — is being betrayed. And the right wing in this country is cheering it on. Stay alert.

Labels:

Politics

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)