Saturday, October 04, 2014

Loss of faith

This 1913 novel by Roger Martin du Gard may come across today as a somewhat curious project, a book that is not only a "novel of ideas" in the sense of being about ideas or structured around ideas but which in fact is largely composed of discussions of those ideas. The period is the late 1890s and early 1900s, a time of open conflict in France between the forces of traditional authority, both clerical and secular, and a vigorous positivism bolstered by scientific advances and by the undermining of religious faith by scholarly criticism. The book consists in large part of responses to that conflict, particularly as viewed through the life of the title character, who inherits both the scientific outlook of his physician father and the pious Catholicism of his mother. In the course of his own intellectual development, the young Jean comes to question and eventually to wholeheartedly reject Catholic teachings; his militant public atheism provokes a breach with his wife, Cécile, with whom he separates brutally shortly after the birth of their daughter. Barois becomes the editor of a prominent freethinking journal, Le Semeur, and is caught up in the Dreyfus Affair, during which he vigorously denounces the decisions of the military courts; later, as his health declines, he is overcome with existential horror at the thought of death and finally relapses into Catholicism. His daughter, whom he does not see again until she turns eighteen, becomes a nun, in part, it is suggested, to ransom her father's soul.

Martin du Gard was not religious, but for the most part he is too scrupulous both as a scholar and as a novelist to openly take sides. A broad range of views are put forward, each of them plausibly articulated, from the uncompromising materialism of Barois's middle years to his daughter's unshakable piety in the face of objections posed by science and reason ("Mais, père, si ma certitude était à la merci des objections ce ne serait plus une certitude..."). Ironies and subtleties abound. Barois, devastated by illness and personal estrangements, reverts to Catholicism; a steadfast friend and collaborator, Marc-Élie Luce, dies serenely an atheist, surrounded by his large and loving family. The priest who guides Barois in his return to faith, secretly troubled in his own convictions, is a longtime admiring reader of Le Semeur who, at the end of the novel, stands by as Cécile burns a document, penned years earlier, in which Barois, foreseeing the possibility of a deathbed conversion, had explicitly denounced it in advance. As the pages burn, the priest thinks of the Church, which had eased Barois's last days, and to which, he concludes uneasily, this sacrifice is due "— peut-être."

Jean Barois looks back at the Dreyfus era, but also prophetically ahead to the debacles of twentieth-century Europe. Before his final return to faith, Barois, like his allies, looks confidently forward to an age in which scientific progress would solve not only medical and technical problems but social ones as well. Martin du Gard foresaw that even as the disappointment of those expectations would lead some, like Barois, to reach for the familiar emotional comforts of faith, it would lead others — notably two young Catholic nationalists who debate with Barois near the end of the book — to an irrational politics that arguably prefigures Fascism. Some, like Luce, face the void bravely and with eyes open; others spiral into despair. One hundred years later the terms of the debate are very different, but the stakes remain the same.

Labels:

France,

French,

Novels,

Roger Martin du Gard

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Unearthly Loves

I started reading modern Japanese literature in Spanish translation because there were a couple of books I wanted to read that didn't seem to be available in English, but at this point I'm just doing it for fun — or perhaps in part because the psychological effect of reading a book in a foreign language — any foreign language — gives me the illusion that I'm reading it "the original," which in the case of Japanese is something I'm utterly unable to do. Plus I just like these editions from Satori in Spain. Putting aside such eccentricities, three of the four stories in Izumi Kyōka's El santo del monte Koya are readily available in English in a volume entitled Japanese Gothic Tales, translated by Charles Shirō Inouye and published by University of Hawaii Press.

And they're great stories, intricately told, shocking at times, richly atmospheric; each of them rewards — in fact demands — a second reading. I'll pass over the two shorter ones, as good as they are, and say a few words about the title story, which in Inouye's translation is called "The Holy Man of Mount Koya," and the novella-length "Un día de primavera" ("One Day in Spring"). Both can be found in the Inouye translation mentioned above.

The former follows a classic Japanese storytelling pattern: a lone traveler — here, a Buddhist monk — hiking through the remote countryside encounters a figure — in this case, a woman — who turns out to be other than what she appears. Kyōka, who died in 1939, was adept at nesting stories within stories, and the events in the tale are actually narrated by the monk to a traveling companion he shares a room with much later. As the monk recalls, during the original journey he had fallen in with a traveling salesman whose vulgar behavior had offended him; the two come to a fork in the road and the salesman chooses a path which, the monk is subsequently informed, will lead him to great danger, perhaps even certain death. After some hesitation, the monk decides that his Buddhist principles require that he set out to persuade the salesman to turn back, since allowing his personal antipathy to sway his duty towards the man would be a great sin. The route he thus follows subjects him to gruesome, skin-creeping horrors — told in vivid detail by Kyōka — but eventually he makes it through, only to find himself the guest of a kind of Japanese Circe, with whom he almost decides to remain forever.

As exemplary a tale as "The Holy Man of Mount Koya" is, it can't quite match the measured, uncanny beauty of "One Day in Spring." Again we have nested narratives, although in this case it is the frame-tale that involves a traveler, a lone figure who arrives at a remote temple and hears from the resident monk a bizarre tale about an earlier pilgrim, who had taken up residence in a nearby cottage and become obsessed with a beautiful woman with whom he had — in this world, at least — only the most fleeting of encounters. Drawn to an isolated spot by the sound of music, the pilgrim had witnessed an oneiric pageant in which he and the woman — or their semblances — appeared as the principle players; a few days later he is found drowned at the edge of the sea. Having heard this strange tale, the second traveler has his own encounter with the woman, then witnesses an appalling and unexpected denouement.

There's at least one additional collection of Kyōka's tales in English, also translated by Charles Inouye and published by the University of Hawaii Press; it's entitled In Light of Shadows: More Gothic Tales. I've ordered a copy.

Labels:

Horrors,

Izumi Kyoka,

Japan,

Tales

Saturday, September 06, 2014

Seeing in the Dark

I read this novel by Rupert Thomson shortly after it first appeared in the US in 1996 and again last week, and both times I had the same reaction: I was impressed with the writing, intrigued by the premise, but more than a bit baffled by the way the story played itself out. Not that the story, bizarre as it is, is particularly hard to follow; but it is, in the end, a little hard to know exactly what to make of it — if indeed that matters.

The story is relatively simple to relate, but I'll just give you the set-up: one Martin Blom, resident of an unnamed European country (most of the names are German- or Slavic-sounding) is shot by an unknown assailant while carrying a bag of groceries across a car-park. The injury, to his head, destroys his visual cortex, leaving him, according to medical opinion, permanently blind. While recuperating in a clinic, however, he discovers that he is in fact able to see, but only in the dark — either that or he is suffering from a phenomenon called Anton's Syndrome, in which a patient, though blind, believes that he or she can see. The truth of the matter is difficult to pin down, especially when Blom also begins to believe that he is receiving television signals through the titanium plate used to repair his skull, and suspects that he is part of an obscure neurological experiment engineered by his doctor. Thomson occasionally drops in little hints that cast doubt on whether Blom is really able to see, but on the other hand there will be an otherwise inexplicable incident in which he drives a car...

Blom is discharged from the clinic and moves into a seedy hotel which may or may not be a brothel (he witnesses things that no one else seems to see, or will admit seeing) and meets a mercurial young woman named Nina, with whom whom he begins an affair that ends when she suddenly vanishes. Following her traces he comes to a remote hotel in the hinterlands, where the proprietress spins a bizarre tale-within-a-tale — about which I'll say nothing — that runs on for more than a hundred pages and concludes shortly before the novel's end.

In one sense, The Insult is simply one more brooding, atmospheric thriller, the kind in which dark secrets will eventually be revealed and the hero (who of course must have his own complicating backstory) will himself become a suspect, at least to the police. It could be objected that Thomson's novel isn't even a very accomplished representative of the genre, leaving too many fundamental matters unresolved and being essentially made up of two only tangentially related narratives. But there's something about Thomson's lean but evocative narration, about the book's unsettling psychological realism even when skirting into territory that, on the face of it, seems wildly implausible, that keeps the reader from feeling cheated.

Thomson has written eight other novels, most recently the fairly lackluster Secrecy. Of the ones that I've read, The Insult and the earlier Dreams of Leaving, which likewise combines an outlandish premise with meticulous writing, seem the most successful.

Labels:

Novels,

Rupert Thomson

Tuesday, September 02, 2014

Plan for an impossible novel

There will be paragraphs.

There will be punctuation.

There will be no epigraph in Greek.

There will be no cell phones, computers, or televisions in the novel because such devices belong to the domain of science fiction and this is not a science fiction novel. The presence of radio and ordinary telephones is probationary.

The novel will be, at least in part, a bildungsroman, because only young people are interesting.

Infidelity in a novel is much easier to make interesting than fidelity; as a consequence there will be no infidelity, except perhaps among characters of secondary importance.

There will be sex.

The novel will take place primarily in an urban setting because the modern novel is fundamentally an urban form, the countryside being more suited to poetry. The city will be made up of layers, like overlapping transparencies, and the movements of the characters will take the form of trajectories across and sometimes through the layers. Since cities are more interesting after dark, most of the novel will take place at night.

There will be no violence unless its presence is impossible to ignore. No civilian character will own or handle a firearm, except possibly for humorous effect, as when Alfred Jarry shoots off a pistol in The Counterfeiters.

There will be no autistic savants, evil albinos, children wise beyond their years, or secrets of any kind.

The novel will be a social novel, in the sense that the way in which society is organized will be one of the determining elements in the lives of the characters. It may or may not be a political novel, in the sense that the characters may or may not participate in or be affected by political movements, but it will not be a novel "about politics" or much less about politicians, few of whom are morally interesting enough to be merit preservation in the pages of a novel.

The novel will not be a contingent novel. That is, it will not be "about" anything the subtraction of which would render the enterprise meaningless.

No character will be stupider than the author of the novel.

No character will be wiser than the author of the novel.

The novel will not end with the death of the protagonist. It will not have a happy ending, nor an unhappy ending. This is not to imply that the characters may not, at the end of the novel, be either happy or unhappy, or both simultaneously.

There will be no sequel.

Saturday, August 30, 2014

The Beast (Óscar Martínez)

A few years ago when I was doing some volunteer tutoring, one of my students was a young man from Guatemala (I'll call him S., though that wasn't his initial) who already spoke and understood English fairly well, even though he was a bit embarrassed not to be able to speak the language better than he did. I don't know whether he was in the country legally (it was none of my business), but he was fortunate in having found a fairly regular full-time job that was a solid step above unskilled casual labor. I have no doubt that he was good at what he did, and it sounded like he got along well with his employer and co-workers, most of whom knew no Spanish. I worked with him for the better part of a year and in the course of the lessons we talked about a lot of things — whatever served as a way of practicing his conversational English — including his job, his life back home, what he did on the weekends, and so on.

Most of the Central American students I worked with had a good sense of humor and were fun to be around, and S. was certainly bright and likeable, but he was a little more serious than most of the others. He didn't seem depressed, like the occasional student who really seemed to be suffering serious culture shock — in fact I think he was fitting in pretty well — but it was clear that he'd been through a lot and was haunted by his experiences. He volunteered one time, without going into details, that Americans had no idea of what people like him had gone through in getting to this country, and I could tell by the look in his eyes that whatever he had personally gone through had to have been pretty bad.

Óscar Martínez is a young journalist from El Salvador who has investigated what may be the grimmest aspect of the ongoing migration crisis: not the crossing of the border itself but the nightmarish journey of Central American migrants through Mexico, an ordeal that annually subjects thousands to rape, murder, and organized kidnappings for ransom as well as to lethal falls from the northbound freight trains known as "the Beast." Unable to travel openly because of their undocumented status, these migrants are preyed upon by violent criminal syndicates who have either bought off local authorities or intimidated them into submission. At every step of the way they are fleeced or threatened; some resist and are killed, others make it through to the border only to be turned around by US authorities. Increased enforcement at the US-Mexico border has only exacerbated the situation, as newly built sections of border wall have funneled migrants into the most dangerous crossing routes, where many are extorted or forced to serve as mules for drug smugglers. Given the odds against them, the motivation that drives them must be powerful indeed. Some come for economic reasons, but as Martínez makes clear, many come simply to save their skins, having been directly threatened by local gangs or having lost family members to violence in what are currently some of the most dangerous societies on Earth: El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

The Beast (the Spanish title is Los migrantes que no importan — "the migrants who don't matter") originated as a serious of articles for the online publication El Faro. Originally published in book form in Spain in 2010, it appeared in Mexico in 2012 and has now been issued in English by Verso Books. It predates, but clearly foreshadows, the recent upsurge in migration from Central America that is being driven by ongoing violence in the region. As a work of primary first-hand journalism, it makes no attempt to propose comprehensive solutions for the migration crisis, but in providing a powerful sense of the human dimension of that crisis its value is immeasurable.

For an update, see the same author's "Why the Children Fleeing Central America Will Not Stop Coming" in the Nation, August 18/25, 2014.

Labels:

Mexico,

Migrations

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

Birth

"The circumstances of my birth weren't extraordinary at all but they were a bit colorful, because it was a birth that took place in Brussels that might have taken place in Helsinki or Guatemala; it all hung on the assignment they had given my father at the time. The fact that he had just gotten married and that he arrived in Belgium virtually on his honeymoon led to my being born in Brussels at the same moment that the Kaiser and his troops launched upon the conquest of Belgium, which they carried out in the days of my birth. So the story that my mother tells me is absolutely true: my birth was an extremely warlike one, the outcome of which was one of the most pacifistic men on the planet."

— Julio Cortázar, from a television interview with Joaquín Soler Serrano for A fondo, 1977.

The exact nature of Cortázar's father's employment in Brussels in 1914 seems to be uncertain; family accounts that made him out to be some kind of minor diplomat or trade official attached to the Argentine embassy are said to be unconfirmed. The family spent the war years in Europe, and when the young Julio Florencio Cortázar eventually arrived in Argentina, he carried with him, according to some sources (but this point is also in dispute), a detectable French accent that would remain with him through the rest of his life. His father — Julio José Cortázar — eventually deserted the family, and it was young Julio's mother and maternal grandmother who would dominate his childhood, but the accident of his parents' sojourn in Europe made him, along with such contemporaries as Alejo Carpentier (born in Switzerland) and Elena Poniatowska (born in France), part of a generation of Latin American intellectuals who moved easily between continents but remained firmly rooted as citizens of the twentieth century and its disruptions.

Sunday, August 24, 2014

Walking Around

Every morning for the past few weeks I've been taking advantage of near-perfect weather and my early-rising habits to go for a long walk before I start the day, and to get better acquainted with the town I've known all my life and have lived in for twenty-five years, something that, no matter how many times one drives through the streets, really has to be done on foot. I get up when the cat wakes me up — generally around six — read the newspapers, eat a couple of eggs, and set out, joining the early-morning joggers and the Central American immigrants already on their way to work at an hour when most of the town is just beginning to stir in their beds. I walk for forty-five minutes or so, sometimes an hour, and whatever route I take I eventually always wind up downtown, where the little stream that runs right through the center of town widens into a slow-moving pool where on some mornings a great blue heron watches for small fish or frogs and turtles climb up on the mud banks, ever alert to retreat into the water at the first sign of commotion.

I walk through the vast silent necropolis on the edge of town, following its circuitous drives and watching crows harass a hawk. In some sections the headstones are mostly those of Italian immigrants of a generation or two go, some with surprisingly evocative names: Manna, Eraclito, Astrologo. In the backstreets live new immigrants, some with carefully tended front gardens lush with sunflowers and vegetables just coming into maturity. Two neighbors greet, in English, discussing one of these little plots. "Y maíz," he says, and regards the developing ear; "soon," he says, in English again. These plantings are too small to be of any economic importance, even to one family's budget; their value is symbolic, a reminder of the milpas back home, a little connection to a distant world and another life.

By eight o'clock or so the town is waking up, the whoosh of traffic beside me is steadier now, and I turn for home. It's time to get to work.

Labels:

Migrations,

Walking

Thursday, August 14, 2014

The Dark End of the Street

There are countless covers of this Dan Penn / Chips Moman tune, some of them very good ones, but to me this live performance by Richard and Linda Thompson is on a different plane from all the rest. The directness and intensity of the vocals, the stark one-guitar arrangement, and the quicker tempo set it apart from the smoother, bluesier versions, and when you listen to it in the context of some of the songs that Richard Thompson was writing during roughly the same period when it was recorded, songs like "Wall of Death," "Walking on a Wire," "When I Get to the Border," or "Just the Motion," it suddenly ceases to be a song about an illicit love affair and is transformed into something much more haunting: a song about the way life relentlessly exposes the vanity of our passions and dreams but can't quite extinguish the defiant longing for something transcendent, call it spirit, call it love, call it God, call it what you will (as if anybody could explain what it is or where it comes from). The real fire is in the bridge, which in this rendition is so stirring it is sung twice:

They're going to find usThere's something here akin to the Borges story "The Secret Miracle," in which a writer is arrested by the Nazis and sentenced to die, but in the single instant before the order is given to the firing squad — an instant that, in his mind and perhaps (who is to say?) in reality as well, lasts for an entire year — is able to complete his unfinished masterpiece in his mind, though it will be known to no one but himself. It's not external circumstances that matter; it's the secrets, the dark interior that no one can see, that provide a final promise of redemption:

They're going to find us

They're going to find us someday

We'll steal away

To the dark end of the street

If you take a walk downtownCall it a love song if you will (and a love song it is), but there's something else here few love songs can aspire to: at once an acknowledgment of death and a furious rebellion against it.

And you take the time to look around

If you should see me and I walk on by

Oh, darling, please don't cry

Tonight we'll meet

At the dark end of the street

We'll steal away

To the dark end of the street

You and me

To the dark end of the street

Thursday, August 07, 2014

War

Our species: an interesting idea, but poorly executed.

Given the inescapable fact of our propensity for cruelty, how is anything else not trivia? It's not just our well-established willingness to ignore the suffering of others; our darkest secret is that given the slightest breakdown in the façade of social customs that keep us more or less on peaceful terms with each other we quickly degenerate into torturers and killers. And once the habit of cruelty begins nothing is harder to break, all the more so when we have, as inevitably we do, our own sufferings that cry for vengeance. No flag is unstained. Blood for oil, blood for land, blood for blood, blood, blood, blood.

Our tragedy is that our technological ingenuity has far outstripped our ability to manage the tools at our disposal in a manner that benefits our own species. How could it be otherwise? How could seven billion individuals with conflicting histories, destinies, and needs ever hope to find common purpose? Where is the will? If we can't find a way of destroying ourselves and much of the natural world around us, we will try harder.

Our overfull boat steams ahead

in the darkness with the pilot fled

and the captain mad

and though we huddle cold and numb

day may not come.

Sunday, July 20, 2014

The Chase

Having read this short novel by Alejo Carpentier in Alfred Mac Adam's translation many years ago, I cockily told myself that I would be able to whip through it now in Spanish in a couple of nights. As it turned out, I made it about thirty pages in, then bogged down and decided to re-read the translation instead first before giving the original another stab.

Why the difficulty? I've plowed steadily through much longer books in Spanish than this one, which is barely over a hundred pages. Though the author was Cuban there's no Afro-Caribbean dialect issue to speak of; there's nothing comparable to the exuberance of Mexican regionalisms found in Elena Poniatowska's brilliant Hasta no verte Jesús mío, for example, or to the elaborate twists and turns of narrative perspective in Cortázar's novels and some of Vargas Llosa's. Maybe I just had too many distractions; in any case, the novel does present some obstacles to the reader, not insuperable ones to a native speaker, perhaps, but enough to make reading it a bit of a challenge. In Spanish or in translation (and Mac Adam's seems to be good), it repays persistence, though.

Carpentier told the critic Luis Harss that he had composed El acoso in imitation of sonata form, "with an introductory section, an exposition, three themes, seventeen variations, and a conclusion or coda." I tend to be skeptical of such claims (Milan Kundera has made similar statements) but in fact the narrative, the bulk of which consists of one long flashback, is framed within an evening's performance of Beethoven's "Eroica" symphony in a Havana concert hall, and probably should be read with that piece of music in mind.

The first character to whom we are introduced is an impecunious classical music buff who is employed as a ticket seller in the concert hall. As he sits in his booth a patron rushes in, flings down a bill many times more than sufficient for even the most expensive seat, and hurries into the hall, closely pursued by two other men. Pocketing the bill (which may or not be genuine), the ticket seller goes for a stroll, calls on a prostitute of his acquaintance, and returns, at the end of the book, in time for the final notes of the performance — and for the brief, violent aftermath of the opening incident. It is the figure he sees fleeing into the hall who will dominate the long central section of the novel. A native of the provinces, this man has incorporated himself into some kind of vaguely outlined revolutionary cell, but ideological purity has degenerated into betrayal and murder-for-hire and he is now a marked man. As we follow the series of steps that lead him to the concert hall events that were narrated in the book's first pages take on new significance.

Carpentier's vocabulary is rich ("baroque" was a word he himself used to define the character of his writing), but the greater challenge is posed by the fact that the reader often doesn't know — and isn't yet supposed to know — exactly what is happening. One section, for instance, begins, in Mac Adam's version, as follows; the ellipses and parenthesis are in the original:

(... this pounding that elbows its way right through me; this bubbling stomach; this heart above that stops beating, piercing me with a cold needle; muffled punches that seem to well up from my very core and smash on my temples, my arms, my thighs; I breathe in gasps; my mouth can't do it; my nose can't do it; the air only comes in tiny sips, fills me, stays inside me, suffocates me, only to depart in dry mouthfuls, leaving me wrenched, doubled over, empty; and then my bones straighten, grind, shudder; I stand above myself, as if hung from myself, until my heart, in a frozen surge, lets go of my ribs so that it can strike me from the front, below my chest; I have no control over this dry sobbing; then breathe, concentrating on it; first, breathe in the air that remains; then breathe out, now breathe in, more slowly; one, two, one, two, one, two ... The hammering comes back; I am shaking from side to side; now sliding down, through all my veins; I am smashing at the thing holding me in place; the floor is shaking with me; the back of the hair is shaking; the seat is shaking, giving a dull push with each shudder; the entire row must feel the tremor;And so on and so on. It's only gradually that we realize that this passage is being told from the point-of-view of the man who has fled into the concert hall; we won't understand why he is there, or why his thoughts are frantically racing, for many more pages. Carpentier professed a disdain for "the little psychological novel" and a preference for the "big themes" of historical and social processes; perhaps the fracturing of perspective here is conducive to that more analytical, even didactic approach. El acoso was first published in 1956; since then its technical innovations have been widely borrowed and extended by other writers, but it still retains its nervy intensity.

Alejo Carpentier's description of the musical structure of The Chase, as well as his comments on the psychological novel, are quoted in Harss and Dohmann's landmark Into the Mainstream: Conversations with Latin-American Writers, which includes a respectful but sharply critical evaluation of the Cuban novelist's work.

Labels:

Carpentier,

Music,

Novels

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

HWY 62

Peter Case is kicking off a Kickstarter campaign for his next CD, HWY 62, which is scheduled to be released in 2015. Details here.

Labels:

Music,

Peter Case

Sunday, July 06, 2014

The living

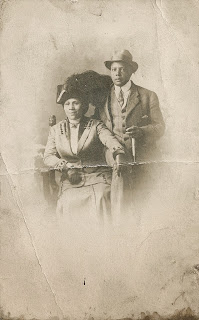

These two faded and stained studio portraits of African-American couples were taken sometime in the early decades of the twentieth century and printed on postcard stock. The one above, which is probably the earlier of the two, is the work of the Flett Studio in Atlantic City, which operated for at least fifteen years or so and must have produced countless similar images. "Mr. & Mrs...," followed by a family name, has been written on the back, but I can't make out the surname. The third figure, standing in the center, may have been the best man at the couple's wedding, or just a relative or friend.

There's even less we can say about the couple below, except that they're dressed to the nines. The studio is unidentified, but the Azo postcard stock used was manufactured from 1904-1918. Like the first postcard, this one was never mailed.

When an artifact is removed from its context without adequate documentation some of its potential for bearing information is lost; we no longer know as much about how it relates to the world that created it. The orphaned photographs above would be much more potent if we knew anything at all about the sitters' identities, life stories, occupations, and families, but people die childless or separated from their families, children have their own lives to lead and can't be bothered, any number of things can sever the thread. Things drift off and go their own ways.

*

The Dead in Frock Coats

In the corner of the living room was an an album of unbearable photos,

many meters high and infinite minutes old,

over which everyone leaned

making fun of the dead in frock coats.

Then a worm began to chew the indifferent coats,

the pages, the inscriptions, and even the dust on the pictures.

The only thing it did not chew was the everlasting sob of life that broke

and broke from those pages.

— Carlos Drummond de Andrade; translation by Mark Strand

Saturday, June 28, 2014

Survivors

Chile, the slender nation that lies along the Pacific margins of South America, has faced more than its share of disasters, natural and otherwise. This neat road novel by the Mexican-born writer Andrés Pascoe Rippey imagines an apocalyptic future in which a nuclear war between the great powers has wiped out modern communications and the electric grid worldwide, even in countries — like Chile — that are far from the center of the conflict. As the authorities lose control, rioting and looting break out, and are followed in turn by the rise of brutal paramilitary units, and, more disturbingly, by armies of crazed, cannibalistic merodeadores (marauders) in whom we — although not the characters, at least initially — recognize the characteristic traits of the zombie.

The novel's central character, Alberto, is a left-wing Mexican journalist living in Santiago. As violence breaks out, he at first withdraws to the security of his apartment, but when the situation in the capital becomes increasingly grim he flees south in a commandeered Range Rover, acquiring two companions along the way. One, Max, is a teenager from a wealthy and conservative Catholic family; the other, Valentina, is an Argentinian woman who is both a formidable hand-to-hand fighter and a sexual powerhouse. Hoping to find shelter in an isolated region, they find that little they encounter along the way — a pious farm family, a neohippie commune — is what it seems; moreover, the paramilitaries and merodeadores are also swiftly making their way south. Much of the latter part of the novel takes place among the idyllic scenery of Chile's Alerce Andino National Park, though the events that transpire there — including, of all things, a cavalry charge, are anything but tranquil.

The novel's political and social overtones are obvious and at time explicit, and memories of the violent dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet are never far from the surface, but the novel also draws on the conventions of horror cinema, as well as, I suspect, books like John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids and the disaster novels of J. G. Ballard. It manages to be well-written and astute in its observation of society and character while supplying a ripping, well-paced narrative.

Todo es rojo is, thus far, available only in Spanish. It has been published, in a handsome edition, by a tiny Chilean press, Imbunche Ediciones, and appears to have limited distribution outside that country. (It is, however, available as a PDF download from Lulu.) Hopefully it will eventually gain wider exposure and translation into other languages.

Sunday, June 22, 2014

Destroying Angels

Kyūsaku Yumeno was the pen name of a prolific Japanese writer who died in 1936 and whose work is apparently relatively little-known in the English-speaking world. Satori Ediciones in Spain has just published El infierno de las chicas (The Hell of Girls), a Spanish-language translation by Daniel Aguilar of the three dark, intricate stories that were originally collected in Japanese as Shōjo jigoku. As far as I can tell the stories have never appeared in English.

All three tales included here are narrated largely or exclusively in epistolary fashion, though in each case we read only one side of the correspondence. One story makes use of fictional news articles, and now and then letters from third parties are nested within the letters of the primary correspondent. The first story, "No tiene importancia," (It's of no importance) takes the form of a long missive written by one physician to another, describing the case of a young woman who has worked as a nurse, first for the recipient and then for the sender. We are told from the first page that the woman, who goes by the name of Yuriko Himegusa, has killed herself; the remainder of the story, which is approximately one hundred pages long, is in effect an extended flashback explaining this act. Himegusa was, to all appearances, a model employee: pleasant, conscientious, skillful, and beloved by her patients. She was also, it seems, a pathological liar, and the eventual unraveling of the skein of lies she has wound around herself proves her undoing. Or does it? Both Aguilar, the translator of this volume, and Nathen Clerici, the author of a recent doctoral dissertation (PDF here) on Yumeno, point out that the final outcome of the story is in fact highly ambiguous; no body is found, and the "suicide" (revealed, naturally, by means of a letter) may simply be one more deception.

From the point of view of the doctor narrating her history, Himegusa represents simply an unfortunate if rather bizarre case of female psychopathology. But Himegusa sees herself as a victim of misunderstanding and suspicion, and her suicide — real or faked — amounts to a salvo in the drawn-out battle between women and a male-dominated world. This aspect is heightened in the two remaining stories in the volume, in both of which the central female characters are at once victims and avengers of the crimes of men. The briefest, "Asesinatos por relevos," (roughly, Murders by relay) takes the form of a series of letters written by a young woman who works as a conductor or ticket-taker on a bus, in which she seeks to dissuade a friend from leaving her rural home and taking up the same career. Her contention that such a career only serves to subject a woman to the whims and abuse of men is chillingly documented in the course of the correspondence, as a new male driver who appears to be a serial killer of women takes the wheel on the bus route she is assigned to.1 In the end, the man gets his comeuppance, although what amounts to a happy ending, in both this and the last story in the volume, may seem appalling to contemporary Western readers.

The final story, "La mujer de Martes" (The woman from Mars), which, like the first, is novella-length, is the most intricate of the three. It begins with a newspaper article about the discovery of a charred body after a fire in one of the outbuildings of a girls' school, and proceeds breathlessly through a series of follow-up reports, which document an increasingly bizarre and inexplicable series of events, including disappearances, a hanging, and the desecration of a cross inside a nearby Catholic church. Only after these events have been catalogued is the explanation teased out, in the form of a long letter from one of the students at the school (the gangly misfit whose nickname gives the story its title) to its headmaster, a pious bachelor who has inexplicably gone insane since the fire. As in the previous story, there is a woman wronged and vengeance to be exacted in disturbing — and in this case extraordinarily elaborate — fashion.

Daniel Aguilar notes that those stories are written from a feminine, almost feminist viewpoint, and there is something to that, bearing in mind the limitations of the time and place (1930s Japan). What is certain is that men don't come off well at all; if not all entirely depraved, they are nevertheless very bad at running things. But there's something more here too, a sense that the world is essentially amoral and devoid of meaning. The men, blinded by lust and vanity, may not acknowledge that fact, but the women know it all too well. In the words of Utae Awakawa, the "woman from Mars":

Little by little I began to feel with greater and greater intensity that the emptiness that lay in the depths of my heart and the emptiness that could be found above the blue sky were exactly the same thing. And I began to think, as well, that the act of dying was something simple and of no importance.2This bleak sense of futility that emerges over and over throughout these stories may perhaps owe something to Buddhist thought, but in its incarnation into 20th-century urban Japan it takes on a character that is very much Yumeno's own brilliant creation.

1 The bus is staffed by two employees: the man at the wheel (conductor in Spanish), and the female cobradora or revisora who accepts tickets and provides assistance to the driver.↩

2 My translation from the Spanish version.↩

Monday, June 16, 2014

Identity

Here are four undated photographs of the same young man, all probably taken within a few minutes of each other. There's a severity to his angular features, projecting an indispensable image of male toughness to a tough world, but as we see him trying out poses — with hat or without, looking now left, now right — do we detect as well a certain lack of resolution, as if he were unsure about exactly how to best project that image?

He selects four different varieties of card mount, to be given away as keepsakes to unknown kin or girlfriends, but they're all passed down together, as if he never did quite make up his mind (or maybe he found that he had no one to give them to). A name scrawled in ink on the back of one of the cards may read "Owen Lewis," but next to it there are also traces of a different set of initials, ornately written in pencil.

The photos themselves are barely more than an inch high, and the embossed cardboard mounts that hold them are about 3.25 x 2.25. Based on the man's hat, collar, and necktie, I'm guessing that the photos date from the early 20th century. They may have been produced in an early automatic photo booth, like the one patented by Anatol Josepho, which debuted in 1925. (The technique of sealing the photos within embossed card mounts originated in the tintype era, decades earlier.)

Labels:

Enigmas,

Photography

Thursday, June 05, 2014

Cold Trail Blues

Peter Case at the Mug and Brush Barber Shop in Columbus Ohio, May 10, 2014.

"Cold Trail Blues" originally appeared on Flying Saucer Blues, and is also included in the compilation album Who's Gonna Go Your Crooked Mile?, both from Vanguard Records.

Labels:

Music,

Peter Case

Wednesday, June 04, 2014

Thursday, May 29, 2014

Russell Edson (1935-2014)

I just learned from Charles Simic's notice on the website of the New York Review of Books that the poet Russell Edson died earlier this year (on April 29, 2014, according to the Poetry Foundation).

I knew Edson's work almost entirely through the one slim volume shown above, which was published as a "New Directions Paperbook Original," apparently in 1964. I doubt I had ever heard of the author when I picked it up second-hand; I was in my teens, it looked interesting, and it probably cost me all of twenty cents, which is the price marked in pencil inside the front cover.

The Very Thing That happens comprises eighty or so very short pieces — what would you call them? prose poems? anecdotes? fables? koans? — accompanied by Edson's own appropriately daft drawings. Here, in its entirety, is one example:

"Someone"I ate it up: the whimsy, the perverse logic, that last line so deliciously cadenced it demanded to be sung (and sing it I did). And likewise with "The Cruel Rabbit," "Notice for the Meatball Fund," "The Tub and the Woman," "Mouse-music," and the title piece, which begins with a father riding into his kitchen on an imaginary white horse and after going downhill from there ends with this incontrovertible bit of wisdom:

A man put a fedora on a cabbage, oh please be somebody I know.

Now who it is, as the brim is low, he cannot tell, but someone is certainly someone.

Someone, who are you?

Someone says nothing.

One and cabbage and now the moon. Round things are not unavailable in a square room.

The moon comes wearing a crown of clouds, worn too low to know who it is.

But why why why is it happening? cries mother.I've hung on to my copy of the book for a least forty years. I can't say that I've dipped into it more than occasionally for a long time, but its spell, in its own small way, has never really been broken.

Because of all the things that might have happened this is the very thing that happens.

Labels:

New Directions,

Poetry

Tuesday, May 20, 2014

The Orphan

Paweł Pawlikowski's Ida is my kind of film: spare, understated, sensitively directed, small in scope but firmly anchored in its time and place, which in this case means Poland in the early 1960s. Sumptuously shot in black-and-white in a narrow-screen format, it's very much a movie to be looked at, the way one looks at still photographs, supplying one's own active eye and interpretation, and not just something to be watched, the way one witnesses a spectacle that's been programmed to hit all the right emotional buttons at the predetermined moments.

The lead character — she's called Anna, a Catholic novice, but she learns that she's really Ida, the daughter of murdered Jews — actually has relatively little to say, usually no more than a few words per scene, and her face betrays little of what's going on inside her head, but she is, in the end, not only the ostensible protagonist of the movie but its audience as well, the one whose fate it is to experience the unfolding of a story that, even as it is about her, is fundamentally not of her own devising. Which is not to suggest that Ida is without a visceral punch. There's something in fact very Greek about it, not so much in the events as in the suddenness and starkness of its emotions, the way the characters — the young novice aside — respond in almost stylized fashion to the revelation of long-hidden secrets, as if purging the collective sins of an entire community.

The trailer below gives an idea of the storyline and the film's beautiful visual style, though inevitably it can't capture its graceful pacing. Stuart Klawans, at the Nation, has a comprehensive and thoughtful review that nicely encapsulates its virtues and ambiguities. I think this is a movie you should see.

Labels:

Film,

Paweł Pawlikowski,

Poland

Saturday, May 17, 2014

Ties

Around the beginning of the 20th century a marriage took place between two nascent media: the postcard, which was becoming the source of an enormous international craze, and amateur photography, a hobby democratized by Eastman Kodak's affordable and portable cameras. The result was the "real photo postcard," continuous-tone photographic prints made directly onto postcard stock, huge numbers of which were created by both amateurs and professionals. While the professional studios made both individual portraits commissioned by customers and mass-produced souvenir postcards in runs of thousands, the amateurs generally made unique prints. Large numbers of the latter survive; although designed to be mailed, many never were, or were enclosed in envelopes and thus never postmarked. Some of the images are fascinating (there are several excellent books devoted to them) but most are fairly dull. They were made for a specific purpose, as keepsakes, to exhibit the likeness of a loved one or the old homestead or the graduating class, imbued with meaning for the photographer and the recipient, but not conveying much to strangers. Separated from their context, they are largely mute.

The obvious amateur image at the top of the page is a little different; while it presents no drama, it does give us a sense of the subject's location and integration within an active, occupied urban space. The card stock was produced by Velox, a company acquired by Kodak in 1902, and this particular variety, which is marked "Made in Canada," was probably manufactured between 1907 and 1914. It bears no address and no identification of the woman in the foreground, although based on provenance I suspect that it was taken in the province of Quebec, perhaps in Quebec City itself. The pyramidal roofs of the skyline at right might potentially make an exact identification of the location possible.

Half of the woman's face is in shadow, as is the street behind her, and a stray fiber appears to have been captured in the printing process at top right, but the image is not without interest in spite of these flaws. If you look carefully (a magnifying glass helps), you can make out on the left side several figures stoop-sitting down the length of the block, the second set of stairs has some kind of ornate stencilled pattern on its vertical surfaces, and there may be an awning projecting from a storefront in the far distance. And then there are the overhead wires, which, like almost everything in this picture, provide a glimmer of connection. The poles, the wires, the street, the sidewalk, the stoop-sitters, the buildings clustered together, all speak of a world in which the texture of an individual's existence is inextricably entwined in sophisticated networks of interaction, communication, transportation, and marketing.

There's no snow on the sidewalk, but there appears to be some piled against the curb on the far side of the street. The child sitting closest to us, who is paying no attention to the woman or the photographer, is wearing a snug wool cap. It's perhaps the end of winter, and the woman has likely removed her own head covering to pose for the camera. A moment later she will move away, but the city that surrounds her will keep on humming even when she's gone.

Labels:

Canada,

Photography,

Real Photo

Sunday, May 04, 2014

The Gloaming

The Gloaming — Iarla Ó Lionáird (vocals), Thomas Bartlett (piano), Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh (hardanger fiddle), Martin Hayes (violin/fiddle) & Dennis Cahill (guitar) — are a quintet of experienced musicians, three from Ireland, and two from the US, whose self-titled first record (above) was released in January 2014. They play a kind of stripped-down Irish trad, by turns haunting and breathtaking, that manages at once to innovate and to draw forth the music's deepest and most ancient core. It's really quite special. Below is one live performance, featuring nine and one-half dazzling minutes of Martin Hayes.

The Gloaming can be purchased from Real World Records or Brassland Records.

Labels:

Ireland,

Music,

The Gloaming

Sunday, April 20, 2014

Helens

I few months ago I signed up for a year's worth of New Directions' Poetry Pamphlets and (prose) Pearls, two series of chapbooks from a publishing company I've long admired but haven't always kept up with. As the books have arrived each month I've found some that I had already seen on the NDP list and knew I would like, like Paul Auster's The Red Notebook which I had read years ago in another format, and a few (definitely a minority) that I set aside after a quick skim. Bernadette Mayer's The Helens of Troy, NY arrived last week (coincidentally as I was re-reading the Odyssey in Robert Fitzgerald's splendid translation) and it's one of the better ones.

This is a modest collection of poetry, perfectly befitting its chapbook format; it's not particularly "literary" in a traditional sense (in the sense in which the poets I usually like tend to be "literary"), by which I mean that although the book includes, among other things, a couple of sestinas, a villanelle, and a sonnet, the language isn't particularly elevated or elaborated in relation to the kind of ordinary conversations that seem to have given rise to the poems. There's no explanatory Foreword or Afterword to the volume (nor is one really called for), but from what one gathers Mayer interviewed a number of women who happened to share a first name and a place of residence, and then worked scraps of their stories and conversations into something like a hybrid of oral history and found poetry, accompanied by black-and-white photographs of the Helens, most of whom are middle-aged or older. (There is one nude — named but mysterious — whom Mayer seems not to have met in person.)

At times fragmentary or cryptic, always unassuming, the poems nevertheless adeptly evoke the particularities of time and place, of what it has been like to grow up and grow old in a city that may have known better days but that hasn't quite given up on itself. (There's an awareness of decline throughout, but no self-pity; one subject proudly holds a bumper-sticker that proclaims "TROY: BACK ON TRACK!") The Helens reminisce about childhood haunts, favorite restaurants, long-dead husbands — or just about what it's like to be named after the most famous woman of antiquity. Names are important here; one of the women, Australian-born, bears the extravagant married name of Helen Hypatia Bailey Bayley [sic], while another, born Helen Mayer (but evidently no relation to the author), quips that she "once met rollo may's son & I thought i was more may [emphasis mine] than he."

Photo at top: Helen Worthington Bonesteel. Bernadette Mayer is now working on a similar project centered on Troy, Missouri.

Labels:

New Directions,

Poetry

Saturday, April 12, 2014

Cassie Burns

The first snows of December haven't yet fallen on the dirty streets of lower Manhattan, but already there's a chill in the air. The photographer, shifting the legs of his tripod and adjusting the camera for just the right view, shudders under his dark frock. It's an overcast morning without much shadow. The little cluster of urchins have observed his preparations, asking him questions and begging him to take their picture. He has waved them off at first but finally agrees, if they will only stand without moving where he tells them to stand, drawing the eye down from that dead expanse of exposed wall. He has other sites to shoot today and can't waste too much time.

A few men, loitering outside the mission or doing business in the shop that pays cash for "old books, newspapers, pamphlets," have been attracted by the commotion and stand in the background, curious but by old habit loath to draw too much attention to themselves. Along the fence there are posters advertising the plebeian entertainments of the week of December 19th — the Windsor, Huber's Museum, the annual ball in honor of John P. Kenney, and Bartholomew's Equine Paradox — but already one of the posters has had patches of paper torn away by the wind or vandals.

The girl lives a few blocks behind where the photographer makes his preparations, at New Chambers and Cherry Streets, an intersection that today no longer exists. Her name is Cassie Burns. She has dark blue eyes and has just turned thirteen, but she's small for her age; there's TB in the family. Wearing an oatmeal skirt, she stands a bit apart from the boys, the usual playmates she watches over almost like a mother. Womanhood is already inexorably separating her fate from theirs. They will be factory workers or soldiers or will join the drunks that haunt the mission; she will have the harder path of motherhood, struggle, lonely old age.

The children, hunched up against the cold in their worn coats, finally settle themselves enough for the photographer to begin. Only after the fact does he notice that two solitary standing figures, one on either side a few yards away, have left ghostly impressions on the glass. The image is issued as a lantern slide bearing the title "N.Y. City — Homes and Ways 62. McAuley Mission, Water St."

✵

The above isn't a "true story," in that I don't know it to be true, but who knows how far it is from the mark? There really was a Cassie Burns in the neighborhood of Water Street and Cherry Hill when this picture was made, in the first decade of the 20th century. It's highly unlikely but not impossible that the girl — if it really even is a girl — is her, but she undoubtedly knew this block well and may well have played with the children shown here. The real Cassie Burns, it is said, would go on to have nine children of her own.

Monday, March 31, 2014

Silver Garden

I know next to nothing about the group called the everybodyfields except that they popped up about a decade ago, made three records that caused some excitement in alt-country/folk circles, then went their separate ways. The lead singer here is Jill Andrews; the bass player and singer to her left is Sam Quinn. When you sing this well you don't need a lot of theatrics. This is pretty close to perfect in my book.

Labels:

Music

Friday, March 28, 2014

Notebook (March 2014)

How many times has this happened? I'm out in a restaurant somewhere, hanging out with friends, and suddenly a song I've never heard before comes on in the background and even though I'm only hearing scraps of the lyrics there's such heartbreak and dignity there that all at once I know that those five or six minutes of music are offering me an answer, a key, the vindication of meaning over the absurd, the proof that against all evidence matter and spirit aren't condemned to incompatible, mutually exclusive destinies. The way the voice is laying down the words across the melody is so perfect, so inevitable, because if there was a revelation, a reconciliation, it would have to be inevitable and complete and final, it couldn't have conditions or qualifications, it couldn't be perfect when seen from one angle but not when seen from another.

And of course later I'm never able to track the song down, even if I know the singer's name, I can't remember the lyrics at all, or if I do track it down it turns out to be just one more hackneyed, hollowed-out artifice, agreeable enough in its way like any number of other things one savors for a moment and then allows to dissipate, gnawing away at the meaning in them until nothing is left, but as its to being an answer to anything, nothing could be more ridiculous.

But what if it was an answer — but only in that moment?

Labels:

Notes

Saturday, March 22, 2014

Dance Respite, Dance Catalan, and if You Can, Dance Hopeful

Translated, with permission, from Tororo's French original at A Nice Slice of Tororo Shiru.

The year 2014 has been decreed the año Cortázar by the relevant authorities.

For the duration of the año Cortázar, the cronopios have deposited receptacles intended to receive contributions towards the financing of the festivities on windowsills, on loose planks at construction sites, on shelves in telephone booths (where these still exist), and in various other locations reasonably well-sheltered from rain (preferably, but not always, because after all one can't think of everything).

These receptacles consist of china tea cups, faux-bronze key trays inherited from grandparents, colored advertising mugs given away by various catering companies, plastic toothbrush-cups, ashtrays recently discarded by the bistros that once utilized them, and aluminum pie-tins; you will easily recognize them, in spite of their variety, because the cronopios, with admirable foresight, have deemed that it would be a shame if these objects served absolutely no purpose until they had been completely filled with money — something which, they are aware, will require the passage of a certain amount of time — and have thus garnished the bottoms of the receptacles with bird seed.

Locate the ones in your neighborhood, and wait before depositing your offering until the birds have eaten all the seed, because it would be a shame if your bills, softened by long circulation, were to be diverted from their fiduciary purpose in order to line the nest of swallows, or that your shiny coins should end up decorating the abodes of magpies.

During the same period, the famas have announced through official channels that in honor of Julio Cortázar they will dance respite on even-numbered days from 4:30 to 5:00 in the afternoon, and that they will dance catalan on odd-numbered days from 5:00 to 5:30.

Green and humid, a cronopio poses on a slab...

... on which someone has carved "Julio Cortázar," somewhere in the cemetery of Montparnasse.

Once there, not really knowing what to do, he smiles with a slightly embarrassed air.

✵

Translator's note: I have borrowed the names of the dances (which are tregua, catala, and espera in the original Spanish) from Paul Blackburn's translation of Cronopios and Famas. Blackburn had apparently worked up a hypothesis, based on the similarity between catala and catalán, to explain the three-fold division of cronopios, famas, and esperanzas along ethnic lines. Below is Cortázar's response, from a letter dated March 27, 1959 that was written in a mix of Spanish (which I've translated) and English. The passages in brackets are missing words restored by the editors of Cortázar's letters:

Let me explain: to dance tregua and dance catala can't be [translated as] "to dance truce and dance catalan," because I never thought that tregua and [catala] had that meaning. For me it's simply a phrase with a certain magic of [rhyme], a sort of "runic rhyme" in Poe's sense. To begin with, catala doesn't [mean] Catalan. Of course now that I've read your division between [Spanish], Catalan, and Madrid businessmen, I wonder if you're not right. Who is right, [the Agent] or the Author? No use to scan the contract. No explanatory clause provided. But, Paul, if Cortázar's Famas dance catalan, is that fundamentally wrong? The Author SAYS, no. Famas may dance catalan and dance truce. Let them dance. I think your philological enquiry is delightful and quite true in the poetic sense of Truth, which is the ONLY sense of Truth. (I am speaking like Shelley, I'm afraid.)In the end, Blackburn's published translation replaced "truce" with the much funnier "respite," but arguably the terms should be left untranslated so that the cronopios, famas, and esperanzas may freely dance tregua, catala, and espera as the spirit moves them. — CK

Saturday, March 15, 2014

Julio Cortázar: A Model Kit

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Julio Cortázar (in the suburbs of Brussels, August 26th, 1914, just days into the German occupation of the city), as well as the 30th anniversary of his death, and last year was the 50th anniversary of the publication of Rayuela, so there has been a predictable amount of hoopla — though apparently relatively little in the US, so far. Cortázar, who was congenitally allergic to hagiography, at least as far as his own public image was concerned, would no doubt have been exasperated by most of this activity, but I think he would have made an exception for this book, which has been lovingly and creatively edited by his first wife and literary executor, Aurora Bernárdez, together with Carles Álvarez Garriga and the book designer Sergio Krin.

Taking their cue from the the experiments with the form of the book that Cortázar himself engaged in, they have assembled an alphabetical "biographical album," which, as the editors state in their introductory "Justification," is "in its way many books but which can be read above all in two ways: in the normal manner (from A to Z) or in a leaping manner, following the spiral of curiosity and chance (AZar). The book thus begins with "Abuela," a two-page spread of pictures of the author's grandmother and a memorial poem he wrote in 1963, and ends with "Zzz...," a brief, sarcastic passage from Rayuela. In between there are reproductions of first editions of his books, postcards, scraps of manuscripts, photographs of friends (my favorite is a priceless shot of Cortázar seated at a table discoursing to a cigar-toting José Lezama Lima), poems and excerpts from his novels, letters, and other writings (some previously unpublished), even his passports and metro tickets. Taking itself lightly, the book includes an entry on "Sacralization," reproducing bookmarks, postage stamps, an abominable coffee mug, and other posthumous Cortázar tchotchkes along with a characteristically tart Cortázar text that makes his own attitude towards such fetishization abundantly clear. Very few aspects of Cortázar's personal life, public activity, and work are left undocumented (Edith Aron, the purported original of la Maga, is one of the few), but the approach through out is respectful but never reverential or ponderous. Above all, like the man himself, it is fundamentally ludic.

Cortázar de la A a la Z: Un álbum biográfico has been published by Alfaguara in Spain; the ISBN is 978-84-204-1593-2. It's only available in Spanish (and wouldn't work in translation, at least in the same format, because of the reproduction of considerable manuscript and typescript material), but anyone seriously interested in Cortázar should seek it out nevertheless, if only for the illustrations.

Labels:

Julio Cortázar

Sunday, March 09, 2014

Favorite son

Burnside Park in Providence, Rhode Island currently sports an installation of rotatable signpost sculptures, including the one shown here, which is dedicated to the horror writer Howard Phillips Lovecraft, a local native.

I have mixed feelings about H. P. Lovecraft in general (q.v. my earlier post), but the handwriting and appropriately ghoulish illustration here seem to hit just the right note. Lovecraft is, in any case, now at least as much a mythical creature as he is anything else, and who knows if perhaps that fate wouldn't have displeased him. So far, I haven't been able to find out who created these sculptures.

Additional (and better) photos can be found in a blog post at Are there Any More Cookies?.

Saturday, March 01, 2014

Keisuke Serizawa: 1969 Calendar

This hand-printed calendar was produced by the Japanese katazome (stencil-dyeing) master Keisuke Serizawa, whose mark can be seen just below and to the left of the bird on the cover print (see following image). He produced calendars, with different designs each year, from 1946 until the mid-1980s; at least one associate and friend, Takeshi Nishijima, produced his own similar calendars during part of that period.

This particular production is relatively restrained. On most of the individual panels it is the numbered squares or circles, rather than the accompanying illustrations, that are the dominant design element; many of the spaces not needed for dates are filled with little vignettes.

For the August print below, Serizawa worked the letters of the name of the month into the first row of the calendar, but since he was one square short he combined the last two letters into one space.

November, I think, is my favorite. Notice that the "S" for Saturday is displaced to a line above the other days, again because there was no empty square available for it.

All of these pages were printed on handmade paper, so the originals are not as neat and square as the images shown here imply.

A variant of this calendar has the name of the Western Automobile Co., Ltd. (the Japanese affiliate of Mercedes-Benz) printed on each page; the image below is from an auction listing.

I am relying on George Baxley for identification on this calendar as the work of Keisuke Serizawa. There are relatively few English-language sources on the artist, with the fine exhibition catalog Serizawa: Master of Japanese Textile Design (Yale University Press, 2009) being the notable exception.

Labels:

Japan,

Katazome,

Printmaking

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)