Monday, January 31, 2022

Norma Waterson (1939-2022)

The revered British folksinger Norma Waterson has died. The Guardian has an obituary and a nice appreciation.

Though she recorded contemporary material as a solo artist, she was probably best known as a member of a family ensemble that in its original conformation in the 1960s also included her brother Mike, sister Lal, and a cousin, John Harrison. Norma's husband, the fine guitarist Martin Carthy (who survives her) replaced Harrison beginning in 1975. Later lineups under various names included the couple's daughter, the fiddler Eliza Carthy.

Below are the Watersons (including Martin Carthy) with a rousing a capella hymn demonstrating the group's unique style.

A documentary entitles Travelling for a Living follows the group in their early days.

Saturday, January 22, 2022

Reading Matter

Henry Mayhew:

I may mention that in the course of my inquiry into the condition of the fancy cabinet-makers of the metropolis, one elderly and very intelligent man, a first-rate artisan in skill, told me he had been so reduced in the world by the underselling of slop-masters (called "butchers" or "slaughterers," by the workmen in the trade), that though in his youth he could take in the News and Examiner papers (each he believed 9d. at that time, but was not certain), he could afford, and enjoyed, no reading when I saw him last autumn, beyond the book-leaves in which he received his quarter of cheese, his small piece of bacon or fresh meat, or his saveloys; and his wife schemed to go to the shops who "wrapped up their things from books," in order that he might have something to read after his day's work.

London Labour and the London Poor

Friday, January 21, 2022

Urban legend

Henry Mayhew, the great chronicler of 19th-century London's working poor, collected the following tale in the course of an interview with a lively street "patterer" who specialized in hawking printed broadsides containing accounts of notorious murders:

Camus had come across the incident in an article published by the Hearst Universal Service, which described it as having taken place in Yugoslavia; he included a brief reference to it in The Stranger before developing it into the play. But it was a shopworn tale even in Mayhew's day. Folklorist Veronique Campion-Vincent, in a 1998 article in the Nordic Yearbook of Folklore (PDF here) traces it back to several versions dating from 1618; within three years versions of the tale had variously located the supposed events in London, Languedoc, Ulm (in what is now Germany), and Poland. Clearly it was too good a yarn not to pass on. (Elements of it — the failure to recognize a long-lost family member — arguably date back to Oedipus Tyrannus and the Odyssey.)

Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, incidentally, is a revelation in itself. A contemporary and acquaintance of Dickens, he combined statistical analysis (mostly omitted in the abridged Oxford University Press edition shown above) with oral history to provide a kind of non-fiction counterpart to the work of the great novelist. He keeps the moralizing to a minimum and allows individuals who would have been long forgotten by now to speak in their own voices. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst aptly calls his four-volume work "the greatest Victorian novel never written."

Then there's the Liverpool Tragedy - that's very attractive. It's a mother murdering her own son, through gold. He had come from the East Indies, and married a rich planter's daughter. He came back to England to see his parents after an absence of thirty years. They kept a lodging-house in Liverpool for sailors; the son went there to lodge, and meant to tell his parents who he was in the morning. His mother saw the gold he had got in his boxes, and cut his throat - severed his head from his body; the old man, upwards of seventy years of age holding the candle. They had put a washing-tub under the bed to catch his blood. The morning after the murder the old man's daughter calls and inquires for a young man. The old man denies that they have had any such person in the house. She says he had a mole on his arm in the shape of a strawberry. The old couple go upstairs to examine the corpse, and find they have murdered their own son, and then they both put an end to their existence.I recognized the outlines of the tale immediately: it's more or less the plot of Albert Camus's 1943 drama Le malentendu, usually translated as The Misunderstanding. Camus shifts the action to Czechoslovakia, replaces the homicidal father with a sister, and changes the machinery of the eventual revelation scene, but it's clearly the same basic story.

Camus had come across the incident in an article published by the Hearst Universal Service, which described it as having taken place in Yugoslavia; he included a brief reference to it in The Stranger before developing it into the play. But it was a shopworn tale even in Mayhew's day. Folklorist Veronique Campion-Vincent, in a 1998 article in the Nordic Yearbook of Folklore (PDF here) traces it back to several versions dating from 1618; within three years versions of the tale had variously located the supposed events in London, Languedoc, Ulm (in what is now Germany), and Poland. Clearly it was too good a yarn not to pass on. (Elements of it — the failure to recognize a long-lost family member — arguably date back to Oedipus Tyrannus and the Odyssey.)

Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor, incidentally, is a revelation in itself. A contemporary and acquaintance of Dickens, he combined statistical analysis (mostly omitted in the abridged Oxford University Press edition shown above) with oral history to provide a kind of non-fiction counterpart to the work of the great novelist. He keeps the moralizing to a minimum and allows individuals who would have been long forgotten by now to speak in their own voices. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst aptly calls his four-volume work "the greatest Victorian novel never written."

Monday, January 17, 2022

John the Bear

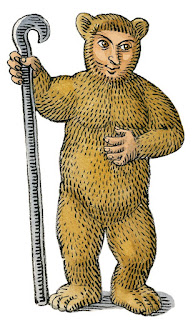

The above illustration by the late French artist Jean-Claude Pertuzé is from a version of a folktale known in French as "Jean de l'ours," that is, John of the Bear or John the Bear. The story of a hero, born to a human mother and an ursine father, who is kept in a cave until he is old enough to roll away the stone that encloses it, and who later descends into the underworld to rescue three princesses, the tale was found throughout Europe and has been carried into the Americas. The German philologist Friedrich Panzer traced a series of parallels between the folktale and the saga of Beowulf, whose name may mean "Bee-wolf," that is, "bear."

The classicist Rhys Carpenter went further, connecting the story, by arguments too intricate to describe here, with the Odyssey, and suggesting a common legendary tradition ultimately deriving from memories of a Eurasian bear-cult. The bear, an animal that immures itself and passes the winter in death-like torpor, has often been conceived of as a messenger to the Other World (as among the Ainu), perhaps as their lord himself. Carpenter mentions the case of the bear-like Thracian hero-god Salmoxis, who, according to Herodotus, built a great hall and regaled his guests with promises of eternal life, before disappearing, apparently dead, into an underground chamber for three years, only to return. In Strabo the same figure becomes co-regent of the underworld.

Is it too much to find here an echo in the New Testament, where the stone is rolled away from the tomb of the risen Jesus after the harrowing of Hell?

The classicist Rhys Carpenter went further, connecting the story, by arguments too intricate to describe here, with the Odyssey, and suggesting a common legendary tradition ultimately deriving from memories of a Eurasian bear-cult. The bear, an animal that immures itself and passes the winter in death-like torpor, has often been conceived of as a messenger to the Other World (as among the Ainu), perhaps as their lord himself. Carpenter mentions the case of the bear-like Thracian hero-god Salmoxis, who, according to Herodotus, built a great hall and regaled his guests with promises of eternal life, before disappearing, apparently dead, into an underground chamber for three years, only to return. In Strabo the same figure becomes co-regent of the underworld.

Is it too much to find here an echo in the New Testament, where the stone is rolled away from the tomb of the risen Jesus after the harrowing of Hell?

Saturday, January 15, 2022

Hermes

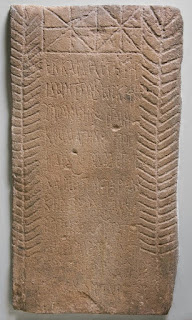

Let some traveller, on seeing Hermes of Commagene, aged sixteen years, sheltered in the tomb by fate, call out: I give you my greetings, lad, though mortal the path of life you slowly tread, for swiftly have you winged your way to the land of the Cimmerian folk. Nor will your words be false, for the lad is good, and you will do him a good service.The Hermes in this third-century Greek inscription isn't the winged messenger of the Greek gods but a teenager who died and was memorialized on what is now known as the Brough Stone, preserved in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. (Original Greek text and details here.) He had done some travelling of his own before he met his end in Roman Britain; Commagene, where he was born, was a small kingdom in what is now eastern Turkey. The Cimmerians, to whose land he flies after death, were a barbarian people known, if hazily, to the Classical world, but in the Odyssey Homer locates their country in the dark regions of the far north, just this side of Hades.

Curiously, Robert Fitzgerald doesn't use the word "Cimmerian" (the Greek is Κιμμερίων) in his translation of Book XI, line 14, but refers instead to "the realm and region of the Men of Winter." It's in Pound's Cantos, though:

Came we then to the bounds of deepest water,

To the Kimmerian lands, and peopled cities

Covered with close-webbed mist, unpierced ever

With glitter of sun-rays

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)