I never saw myself as, and resist becoming, the wholesome ‘outdoors’ type. But the things I experience keep dragging me in. There are moments that thrill and glow: the few seconds a silver male hen harrier flies beside my car one afternoon; the porpoise surfacing around our small boat; the wonderful sight of a herd of cattle let out on grass after a winter indoors, skipping and jumping, tails straight up to the sky with joy.I came upon Amy Liptrot's memoir "by accident," by way of the film adaptation starring Saoirse Ronan. But what constitutes an accident? Most of The Outrun takes place in Orkney, a place that has long interested me because of its geography and long history of human occupation, and if it had been set elsewhere I might never have been aware of it.

I am free-falling but grabbing these things as I plunge. Maybe this is what happens. I've given up drugs, don't believe in God and love has gone wrong, so now I find my happiness and flight in the world around me.

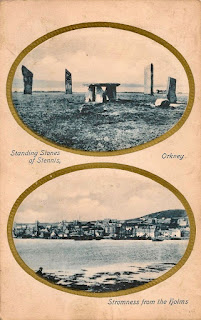

Liptrot was raised in Orkney (of English parents) but as a teenager couldn't wait to get away from it. She spent a decade in London going to clubs, finding and losing jobs, and — most of all — drinking. She tried and failed to get off the bottle various times, but finally succeeded, with the help of a treatment program, when it became clear that she was facing a choice of either life or booze. She retreated to Orkney, got a summer job with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds counting elusive corncrakes, then rented a cottage on the tiny, treeless island of Papay (population less than one hundred).

The memoir and the film adaptation both have merits, but they're different merits. The movie is darker and more intense (and occasionally frustratingly non-linear); it focuses more on Liptrot's hellish and frenetic London years; the book is retrospective and meditative, following Liptrot as she retunes herself to the rhythms of the islands. Overall the film is faithful, and Ronan's high-energy performance is wonderful.

There is, of course, a movie tie-in edition with Saoirse Ronan on the cover, but I opted for this earlier Canongate paperback edition with cover art by an artist who works under the name Kai and Sunny.