This hardbound German-language "Golden Jubilee Calendar" was issued in New York in 1898. An item in Publisher's Weekly (December 4, 1897) announced its publication:

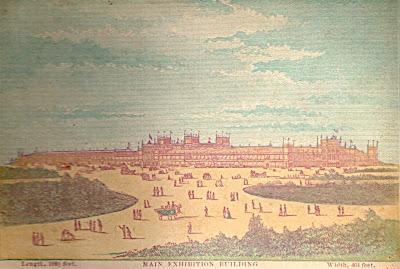

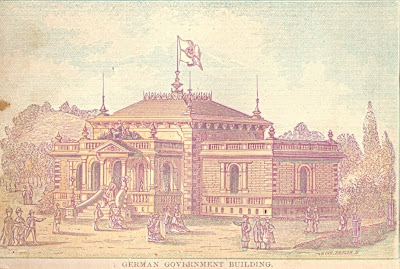

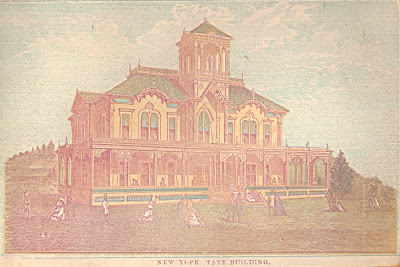

Lemcke & Buechner in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of the firm of B. Westermann & Co., to which they have succeeded, have issued in book form "Meyer's Historisch-Geographischer Kalender" for 1898. This calendar, which contains useful historical and geographical information, was formerly issued in the shape of a pad, and so had only ephemeral value. In book form it will no doubt be acceptable to a wider circle than heretofore.Each day of the year is decorated with an engraving or other illustration, mostly of points of interest although there are vignettes of such worthies as Martin Luther and Walter Scott as well. The calendar's pages are extremely brittle and the binding is in a ruinous state, though enough of it remains intact to make it difficult to get undistorted scans of a few sample pages:

The versos and endpapers of this copy were used as a diary and scrapbook by an American girl in her teens who lived in New York City. She was not from a German-speaking family but was apparently learning German from a governess, as the entries occasionally mention someone referred to only as "Fräulein." I've been able to identify the diarist, who belonged to a fairly well-to-do Manhattan family with military and political connections. Though her diary has no great literary merit, it preserves interesting glimpses of her daily round of social and educational activities, including visits to West Point, Warwick (New York), and other locations.

Monday Dec 27 I packed my trunk and Tuesday I went to West Point & Mama and Papa went to Washington. I took an early train, arrived at twelve and found Bus (?) waiting for me. After lunch she & I went to see the yearlings drill. Capt. Parker had hurt himself the day before and another man drilled them. Later we met the Jackson kids Maud & Evelyn and we had a short talk with their brother. Wed. afternoon we had a tea at the Parkers & I met about 35 - 40 cadets....On several pages she sketches and describes the designs of dresses she was making by hand:

Though the handwriting in the above pages is sometimes difficult to make out, it is often far worse elsewhere in the diary. Confined as she was to a single page per day, when she had a particularly busy day she simply wrote smaller. On a couple of occasions she filled the page, rotated the book 90 degrees, and wrote over what she had already written. It was as if she despaired of leaving anything out, as if she realized all too well that in time her words would be all that remained.

The young diarist later married, had children, and eventually died at an advanced age. I have no way of knowing whether she ever kept a diary again.